Slapstick Tragedy:

The Story of Clyde Bruckman in a Prologue, Five Acts, and an Epilogue

Prologue

In the world of film comedy, people who work creatively behind the cameras know how lucky they are to find one or two genuinely gifted performers with whom they can click and produce a special kind of fun, something where they both can get beyond themselves. One writer/director, however, received a true blessing from the gods – if only in the comedy he got to make in his lifetime. His personal fate, spiritually and professionally, was a lot more bleak, and that darkness has also eclipsed his posthumous renown. Yet his body of work is incomparable. Starting out in the late 1910s as an uncredited gagman for Roscoe Arbuckle, he went on to work in the same capacity on most of Buster Keaton’s great two-reelers in the early 1920s, and finally became one of the three credited scriptwriters for Keaton’s first five classic features. In 1925 he moonlighted at Mack Sennett Studios to co-script one of Harry Langdon’s finest two-reelers, and then worked as an uncredited writer on Harold Lloyd’s greatest comedy, The Freshman. The following year he proposed a property to Keaton, about a Confederate engineer trying to rescue his train from Yankee spies. He became a director on The General, sharing the helm with Keaton, and stuck with directing for the next eight years. At the Hal Roach Studios he directed Laurel & Hardy in some of their most memorable silent two-reelers, just as their characters were crystallizing.

When sound came in, he rejoined Harold Lloyd as director and co-writer for two of Lloyd’s best talking comedies; after that, he directed two of W.C. Fields’ funniest films, short and feature. He stopped directing after 1935, and over the next ten years at Columbia scripted some of the best of the Three Stooges’ two-reelers; while there, he also provided first-rate work for, among others, Andy Clyde, Hugh Herbert, and his former mentor Buster Keaton. The fun ended when the studios that had released films he’d scripted were sued by Harold Lloyd, because he had reused gags from some of his comedies with Lloyd. After Lloyd collected in 1947, he never got another job in the movies again. By the early 1950s the only door open to him was television, and there he had one last hurrah, writing some of the best episodes of “The Abbott & Costello Show.” Bud and Lou were also having their last hurrah, and gave their funniest performances of the decade in these shows; but after they were cancelled in 1954, he had no more work. On January 4, 1955, at the age of 60, he put a pistol to his head and pulled the trigger.

I’ve been deliberately withholding his name, partially in deference to the oblivion that has claimed it – you have to respect a silence that can drown out so astounding a resumé, one that has never been surpassed: Nobody in the history of film comedy worked more intimately with as many masters at the top of their form. Neither the legendary producer/directors Mack Sennett and Hal Roach, nor such veteran comedy writer/directors as Leo McCarey or Jules White or Eddie Cline or George Marshall or Frank Tashlin, achieved so many creative peaks in their careers.

That a maker of so much sublime comedy should also have endured such a tragic end may be one reason why his name has been so consistently sidestepped: He’s just too much the memento mori, too ominous a note to sound, if all you’re trying to do is document the laffs. Don’t bother looking for his name in a shelf-load of titles on Keaton, Fields, Langdon, Lloyd, Laurel & Hardy, the Three Stooges, and Abbott & Costello. Historians and critics of previous generations, however, recognized his importance. “A first-rate comedy man” was the call by William K. Everson. For Kevin Brownlow, he was “one of the best gag men in the business,” and for Leonard Maltin, “one of the all-time great comedy writers.” Kenneth Anger, master avant-garde filmmaker and a chronicler of the movie industry’s shadow life, summed him up as “one of the key figures in the history of American screen comedy.” Yet some revisionist film historians have insisted that this man deserves his obscurity; they see him as only a hanger-on to the greats, a temporary cog in their various machineries. To this mentality, he’s a Forrest Gump, directing Fields or Lloyd or Laurel & Hardy simply by saying “Action,” “Cut,” and “Print it” when he’s supposed to, like Gump shaking the hands of Kennedy and Nixon, even though his mind cannot grasp their significance. In other words, he was the world’s luckiest son of a bitch – at least until he killed himself.

That image tells us even less than the Death’s Head cliché does. A closer examination of his work reveals something of value underneath all the projections: a writer/director named Clyde Bruckman, who for over thirty years helped create some of America’s greatest film comedy.

Act I: Silents are golden

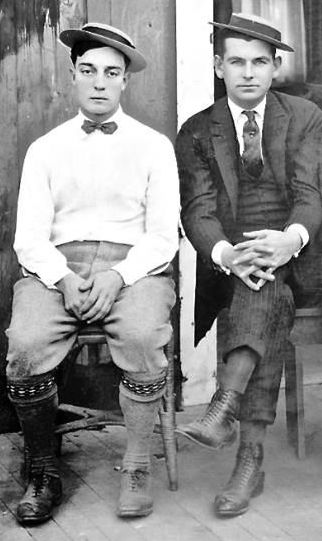

Clyde Adolph Bruckman was born in San Bernadino, California, on September 20, 1894. Reputedly a high-school graduate, he’s said to have worked as a sportswriter on the Los Angeles Examiner in the late teens, and after that toiled among the uncredited gagwriters working for Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle on his two-reel films for Comique, made from 1917 to 1919. Working at Comique as a gagman for Arbuckle meant that Bruckman had started at the top, alongside a master clown who was then at his peak. The same can be said of Buster Keaton, who entered films in 1917, supporting Arbuckle. When Arbuckle’s Comique productions relocated from New York to Long Beach, California, Keaton went along, appearing in nine more of Arbuckle’s comedies. With Arbuckle’s graduation to making features in 1920, Keaton was able to launch his own series of shorts. In addition to Keaton, Bruckman would have encountered others in Arbuckle’s circle, with whom he’d collaborate in the 1920s, such as future Keaton writer Jean Havez and gagman/actor Mario Bianchi, who would go on to star in his own comedies as Monte Banks.

Bruckman’s earliest credited writing work, as “C.A. Bruckman,” is the Star/Universal 1919 release Three in a Closet, a one-reeler produced and directed by its stars, the comedy duo of Eddie Lyons and Lee Moran. They began making films as a team in 1915 and soon ranked among the top moneymakers at Universal. From there Bruckman went to Warner Bros. – or rather, the 1920 idea for Warner Bros., which was teetering on closure by the following year. Some three decades later, Bruckman described that studio to Keaton’s biographer Rudi Blesh: “Warners at that time consisted of Jack, Sam, and Harry Warner, Monte Banks, and a few extras and props, in an old barn of a studio at Bronson and Sunset.” As an uncredited writer for Banks, Bruckman could have been involved in such 1920 Warners shorts as A Flivver Wedding, His Naughty Night, Nearly Married, and A Rare Bird; but by 1921 he was more than ready to jump ship – especially once Harry Brand, Keaton’s publicity man, asked Bruckman to join Buster’s team of gagmen.

Keaton co-wrote and co-directed all his silent shorts with Eddie Cline, a former Keystone director; the exceptions are The Goat and The Blacksmith, where he shared the duties with another Sennett alumni, Mal St. Clair. During those years Keaton also kept various uncredited gagmen on hand, three of whom became increasingly important in making his comedies: Bruckman, Jean Havez (who’d been a writer on Keaton’s last three films for Arbuckle), and vaudevillian Joe Mitchell. Bruckman’s involvement with Keaton can be traced back at least to the October 1921 release The Play House, which he spoke of to Blesh. Yet seeing as how Bruckman would reuse material from the May ‘21 release The Goat, it seems likely he was working with Keaton by the time of that gem – one of a dozen shorts made between mid 1921 and early 1923, which defined Keaton as the funniest and most original American-born film comedian. Attending the sacred mysteries of such classics as Cops and My Wife’s Relations, Bruckman was initiated into a new way of thinking funny. He also got to play a lot of bridge when the work or the weather stalled, and a lot of baseball whether anything had stalled or not.

Keaton completed his last short late in 1922, and while he and Cline were preparing his first feature, Three Ages, Bruckman did uncredited work on Glad Rags, a two-reel comedy starring former pro wrestler Bull Montana. The producer and writer was Hunt Stromberg, who in the 1930s would produce many hits for MGM, including the “Thin Man” films and the musicals of Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald. Stromberg made a bundle with a series of Bull Montana comedies, inevitably placing his neanderthal figure amid refined situations. Bruckman went on to script Montana’s 1923 three-reeler Rob ‘Em Good, a Robin Hood send-up produced and directed by Stromberg. “Why Metro continues to feature this ex-wrestler is beyond human comprehension,” groaned Harrison’s Reports, but Rob ‘Em Good was Bruckman’s first screen credit since Three in a Closet, which means since ever; another solo too. In September of 1923, one week before Three Ages was released, his name was again onscreen, as title-writer on the chorus-girl comedy/romance Rouged Lips, a vehicle for Metro star Viola Dana. She was a popular heroine of the day, which means Bruckman received a real compliment when an anonymous critic at Variety wrote, “Next to Miss Dana’s acting, the subtitles are the best. Written by Clyde A. Bruckman.”

Only after Rob ‘Em Good and Rouged Lips did Bruckman’s name appear on a Keaton film. On Three Ages Keaton continued to co-direct with Cline, but the writing credit instead went to Bruckman, Havez, and Mitchell. This six-reel feature puts Buster through his paces as a caveman, ancient Roman, and modern American; despite the narrative connections, it plays very much as three two-reelers intercut together – indicating that the change in credit reflected more the contractual demands of Keaton’s writers, now in the big time of features, rather than any real shift in how the five men made comedy.

A shift did come, however, after Cline departed to resume directing for Sennett. Keaton began developing feature-length stories with Bruckman, Havez, and Mitchell, and made four superb films in a row, starting with Our Hospitality (1923), a clan-feud comedy that Keaton co-directed with John Blystone. The surreal detective satire Sherlock, Jr. (1924) was Keaton’s most audacious and technically accomplished film, and his first solo credit as director. With The Navigator (1924), Keaton had his biggest commercial hit thus far; but concern over the logistics of filming his struggles with a runaway ocean liner prompted him to bring in Donald Crisp as co-director. Keaton alone directed Seven Chances (1925), in which Buster announces he will inherit a fortune if he marries, and thus winds up being chased by hordes of voracious brides. But after that, the writers who had helped Keaton create his comedy all scattered.

Bruckman had already strayed after The Navigator, when he wrote for a star who was about to burn as brightly as Keaton, Chaplin, or Lloyd: the childlike Harry Langdon, whose slower, subtler humor brought a new dimension to silent comedy. Mack Sennett had begun releasing Langdon two-reelers in 1924, certain that he had a potential star on his hands, but clueless when it came to developing Langdon’s unusual talent. That miracle was performed by writers Arthur Ripley and Frank Capra and director Harry Edwards. Together they made a series of hilarious shorts, and Langdon & Co. were launched into features by 1926 – a good fortune Langdon throttled the next year, demolishing his career by trying to write and direct himself. But while at Sennett, Capra was also being farmed out to work on two-reelers for Ralph Graves and Ben Turpin, and so Bruckman was hired to write with Ripley, creating one of Langdon’s best shorts, the bearded-lady love story Remember When?.

Bruckman then returned to Keaton for Seven Chances, and from that great blend of farce and slapstick he would in later years rework gags for the Three Stooges and Abbott & Costello. Keaton, however, is said to have held Seven Chances in disfavor, perhaps because for him it marked the end of an era. After three intense years, it was his last film with Mitchell, Havez, and Bruckman – Harold Lloyd had swooped. America’s most successful film comedian (alongside Chaplin), Lloyd was able to hire the people he needed to make The Freshman his best film yet. Havez and especially Bruckman did uncredited writing on what would be Lloyd’s masterpiece, a brilliant college-days satire that showcased Lloyd’s mastery of character comedy and gag construction.

Bruckman then answered an appeal from his old friend Monte Banks, who had begun starring in features, and co-scripted Banks’ 1925 release Keep Smiling. He then returned to Lloyd, along with most of Lloyd’s team from The Freshman, for the feature For Heaven’s Sake (1926); this time, however, Bruckman would be a credited co-writer. Although a funny film and a hit with the public, For Heaven’s Sake didn’t repeat the magic of The Freshman in either regard, and its reputation has been overshadowed by the Lloyd classics that preceded and followed it – which is regrettable, because For Heaven’s Sake provides an excellent balance of Lloyd’s sentimental vein with his comic gifts, and offers such memorable set pieces as Lloyd crowding a sidewalk mission with a gang of street thugs.

As a comedy writer, Bruckman now enjoyed one of the best seats in Hollywood; but it was worth leaving Lloyd when he got the chance to write and direct with Buster Keaton. After the departure of Bruckman, Havez, and Mitchell, Keaton had directed Go West (1925) from his own story, playing a character named “Friendless” whose sole companion is a cow. Alternately pleading and cold, Go West is a lesser Keaton feature; its follow-up, Battling Butler (1926), was made with another set of writers and is even thinner and less funny – and it begs for sympathy by having Buster pummeled in a boxing match that isn’t played for laughs. Yet Go West was a hit, and – go figure! – Battling Butler became Keaton’s biggest moneymaker of all. Now he could make films as an independent, releasing through United Artists just as Chaplin did. So he said yes when Bruckman pitched a Civil War fracas about railroad trains. But after having embraced Keaton’s most pedestrian work, audiences ignored The General, his most elaborate and inspired comedy. Its failure cost Keaton his career as a director, and he’d never direct his own work again.

The General, however, turned Bruckman into a director, and he helmed two Monte Banks features of 1927, Horse Shoes and A Perfect Gentleman. Both films were funny and well received, but Banks decided to go to England and work there mostly as a director. He wouldn’t return to the States until the outbreak of World War Two, when he directed his only Hollywood feature, Great Guns (1941) starring Laurel & Hardy – who by then were on a sad slide down, struggling with stale material written by studio hacks at 20th Century-Fox. But when Bruckman began directing Laurel & Hardy back in 1927, Banks had just ended his career as a minor 1920s comedy star, while Stan and Ollie were just beginning their career as the greatest comedy team in the history of film.

Of course there was no Laurel & Hardy when Bruckman arrived at Hal Roach’s lot in mid 1927. Prior to being directed by Bruckman, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy had appeared together in nine different short films produced by Roach; they’d played off each other in a variety of relationships, only one of which, the early 1927 release Duck Soup, anticipated their mature work. Both were still appearing separately as well – Laurel’s last film appearance without Oliver Hardy, the two-reeler Should Tall Men Marry?, was directed by Bruckman. It was one of his first efforts directing at Roach, and the only film he made there without the involvement of Leo McCarey, then a vice-president and production supervisor at the studio.

Hal Roach is said to have brought in Bruckman to direct Max Davidson, a popular ethnic comedian whose Jewish-themed two-reelers could be filled with funny gags. He helmed two of Davidson’s 1927 releases, Love ‘Em and Feed ‘Em and Call of the Cuckoo. The former has one of Oliver Hardy’s last short-comedy appearances without Stan Laurel; in the latter, the two are not only together, but also very much a team – if only for a brief appearance, as a pair of mental patients. Max’s property has become a visiting ground for lunatics from a nearby asylum, which enabled several Roach luminaries to put in cameos: James Finlayson, Charlie Hall, Charley Chase, and Laurel & Hardy all get to cut up on Max’s lawn. The boys look especially demented with their heads shaved, having then been in the midst of playing convicts in their own two-reeler, The Second Hundred Years – the film in which their characters finally settled into place. Their scene in Call of the Cuckoo, goofing through a William Tell routine, is the first time either McCarey or Bruckman worked with the boys, made at virtually the moment they became The Boys.

This newness still clings to Putting Pants on Philip, the first of four Laurel & Hardy shorts Bruckman directed. It’s the last time Stan and Ollie play opposite each other as differently named characters, but already much of the team’s dynamics were in place. Laurel had only to lose his libido, which here is proto-Harpo, with Stan as the randy Philip expressing his enthusiasms in gazelle-like sprints after random women – an oversized heterosexuality perhaps deemed advisable because he was playing a Scottish newcomer who draws startled crowds by walking the streets of Los Angeles wearing a kilt. Laurel immediately divested himself of libido and kilt, and the next three shorts he made with Hardy – and with the attentions of Roach, McCarey, and Bruckman – are in each case quintessential Laurel & Hardy films. Stan and Ollie may be throwing literally thousands of pies in The Battle of the Century or visiting the dentist in Leave ‘Em Laughing or building a house in The Finishing Touch, but whatever they do, they do it as though they’d been working together all their lives.

Between 1927 and 1935, Bruckman’s only credit strictly as a writer is for the man who’d made him a director. Buster Keaton’s other two United Artists releases, College (1927) and Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928), were both first-rate works, yet these films flopped even worse than The General had. Bruckman left Roach to rejoin Keaton at MGM, where the once-independent star was now a contract player. Co-scripting Keaton’s 1928 release The Cameraman, Bruckman could see how the studio wanted to control the comedian’s open-ended methods. The Cameraman managed to emerge Keaton’s way, but he was more constrained in his Bruckman-less follow-up Spite Marriage (1929) – Keaton’s last silent feature. After that, MGM switched to sound and exerted a total – and fatal – control over Keaton’s films.

Act II: Talk isn’t cheap

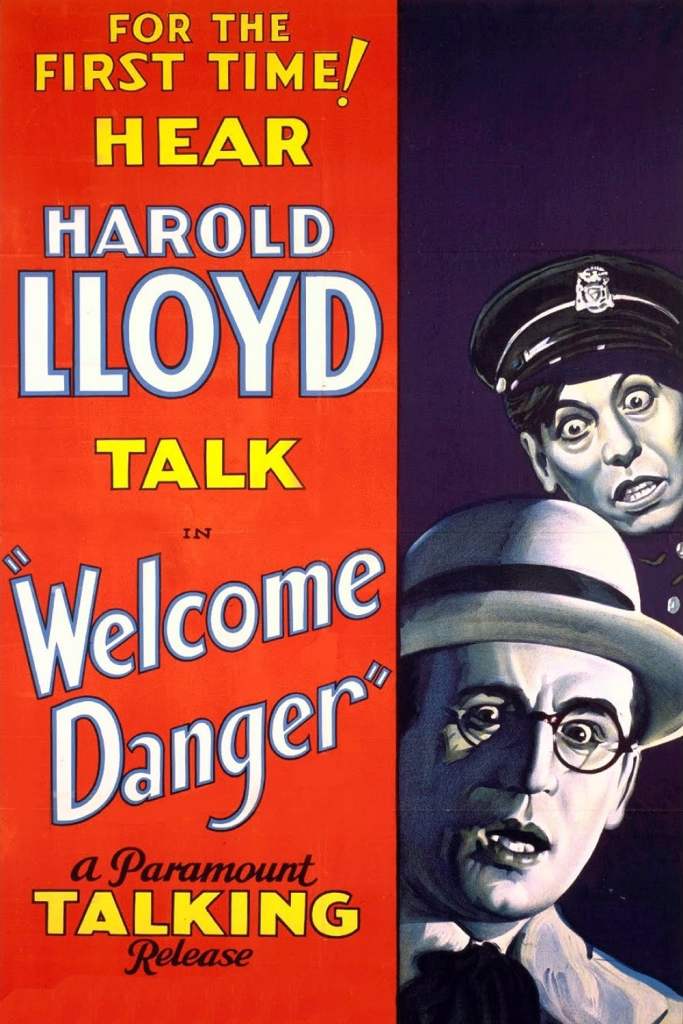

Bruckman left just before Keaton’s career hit the skids, returning in 1929 to Harold Lloyd, who was trying to switch to sound without losing control over his films. Lloyd’s twelfth silent feature, Welcome Danger, had been directed by former Keaton collaborator Mal St. Clair; but the film came out with a running time of almost three hours, requiring Lloyd to spend months reducing it and testing it. The talkies, however, were so quickly changing America’s theaters that Lloyd realized Welcome Danger would be archaic by the time he could release it. So he hired Bruckman to rewrite and reshoot certain scenes with sound, then dub the rest of the silent footage and cut everything together into a talkie. Released in October of 1929 with both St. Clair and Bruckman credited as directors, Welcome Danger became Lloyd’s biggest box-office hit since The Freshman – a success due entirely to the newness of sound and audiences’ eagerness to hear their favorite stars talk. On those rare occasions when the film is screened today, it plays as every bit the lumpy, misshapen Frankenstein it is.

Welcome Danger also gave Bruckman a chance to write with gagman Felix Adler, who would be his frequent collaborator at Columbia in the early 1940s – although their teamwork actually began in 1925 with Langdon’s Remember When?, for which Adler co-wrote the titles (suggesting that Bruckman may not have met him on that film). Lloyd kept most of his team together for his next two talkies, and had Bruckman directing and co-scripting with Adler and others. He wanted Feet First (1930) to surpass the building-climbing thrills of his silent classic Safety Last (1923), and it did just that, in a nightmarish sequence that is more entertaining to today’s hardened viewers than it was to audiences of its day, who were dismayed by the realness sound brought to Lloyd’s desperate efforts not to fall off the face of a building. The box-office was weaker on the Hollywood satire Movie Crazy (1932), although this clever, gag-filled look at the movie industry is now regarded as Lloyd’s finest sound film – which is no small deal, considering that the other contenders are Leo McCarey’s The Milky Way (1936) and Preston Sturges’ The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1946). Although Feet First and Movie Crazy didn’t hit as big as Welcome Danger had, both were profitable; what makes them so special, however, is that Lloyd was still doing the kind of comedy he did best – a luxury that sound never permitted Keaton or Langdon.

In between Feet First and Movie Crazy, Bruckman spent two weeks at RKO directing Everything’s Rosie, a 1931 release which starred Robert Woolsey in his only feature appearance without his partner Bert Wheeler. But the cigar-chomping funnyman was somewhat overburdened as the con-artist lead, and the results were poor. Today even Wheeler & Woolsey enthusiasts despise the film for splitting the team. RKO had made six successful comedies with the duo since 1929, but thought they could be twice as profitable working separately; instead the studio got two flops, because Everything’s Rosie tanked just as badly as Wheeler’s Woolsey-less Too Many Cooks did that same year. RKO promptly reunited them and kept them together until Robert Woolsey’s death in 1938.

After that thankless gig, Bruckman must have been glad to return to Lloyd. Yet the first bad story of Bruckman and alcohol comes from the set of Movie Crazy. Years after Bruckman’s death, Harold Lloyd recalled of the film, “I got one of the gag men to direct and he had a little difficulty with the bottle and we practically had to wash him out and I had to carry on. […] But I still gave the credit to this other boy, the gag man, for it. I felt it helped them. I didn’t see that it was going to add to my prestige, and certainly from a monetary standpoint it wasn’t going to help me any more, and it did help them.” Accounts all agree, at least with each other, that Bruckman was a heavy drinker and liable to be unavailable for work from time to time – a tolerable frailty in a gagwriter, but a catastrophe for a director.

Liquor flowed plentifully in Hollywood throughout the Prohibition years, which means Bruckman had to be hitting the bottle awfully hard to mess up his career this badly. Barring outside tragedies, his story appears to be a classic case of success phobia: From out of the valley of gagmen, Bruckman had arrived, just as McCarey and Capra had arrived, into the peaks of the director’s chair, writing and directing for one of Hollywood’s greatest comedians – and yet he’s too drunk to function on the set of Movie Crazy. Lloyd’s having covered for him may have made all the difference in his getting another job so soon, because by late 1932 Bruckman was directing again; maybe only two-reelers, but he was making them for Mack Sennett, the father of American silent comedy.

That particular offspring, alas, had passed away a few years earlier, and Sennett’s career was now nearing its demise too. He’d pretty much run out of name players back in 1928, when he switched over to sound shorts and went from the mighty Pathé as his distributor to the humble Educational. Sennett was brilliant at discovering and launching talent – the list includes Mabel Normand, Arbuckle, Chaplin, and Langdon – but he was too tight with a buck and too narrow in his demands to hold onto his artists. He’d just parted with Educational and was producing shorts for Paramount when Bruckman arrived in mid 1932, but this apparent step up only delayed the inevitable for a matter of months, and in 1933 Sennett declared bankruptcy and closed his studio.

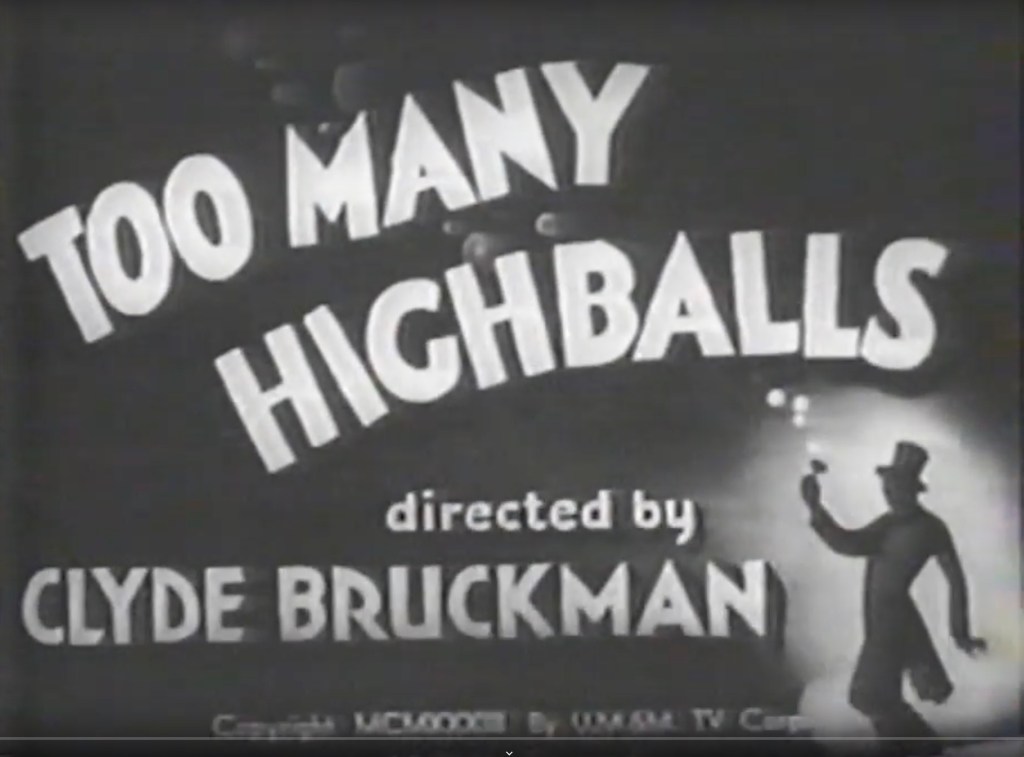

Bruckman made only three shorts for Sennett, and each title offers an eerie allusion to the perils of boozing: The Human Fish, Too Many Highballs, and The Fatal Glass of Beer. The third film, Bruckman’s last Sennett release, is an early classic by W.C. Fields; the other two are largely unknown today.

The Human Fish, however, is not about someone who drinks like one, but rather a tribute to a renowned young athlete of the day: Helene Madison, the American swimmer who’d won three gold medals at the Olympic Games held in Los Angeles in August of 1932. Keen to capitalize on her popularity, Sennett signed Bruckman to a contract on November 8, and a week later shooting began on a collegiate comedy then called Help! Help! Helene! – Bruckman was still working on the script during the five-day filming, from the 15th through the 19th. He had written gags for Bull Montana, and he could write gags for Helene Madison; but for insurance her co-star was the great comic actor and sissy-role specialist Franklin Pangborn.

Too Many Highballs is one of the last starring films of a comedian who has become a legend all too literally. Lloyd Hamilton’s short films of the mid 1920s, released through Educational, had won him acclaim; but a warehouse fire consumed most of the negatives, and today our sense of his work is sketchy. Talkies were a brick wall for Hamilton, and by the end of 1932, after a few years of cheap two-reelers and small roles in features, he was in bad health and drinking too much. At age 41 he seems old and disengaged in Too Many Highballs, and his persona, perhaps more elfin in silents, comes off as just slow and tired. Sennett had tried teaming Hamilton with comedienne Marjorie Beebe, but they never caught on – certainly each plays their best scenes in this film without the other. Although Sennett was hurting for stars by then, he didn’t present Hamilton as one: The lead performer is just the first of four names on a “Players” card. Other than Sennett’s, the most prominent name on the film is that of Clyde Bruckman. Although credited only as director, he plainly wrote most of this funny opus, and his scenario was one that he would reuse more than once.

Hamilton plays poor-soul character Harold Hobbs, whose home sweet home with his wife Beebe is blighted by the indefinite residence of his gruff mother-in-law and his unemployed brother-in-law Claude, a pair of abrasive moochers who start their day by pouncing on Hamilton’s newspaper and devouring all the breakfast. Before Hamilton leaves for work, Claude even hits him up for yet-another quart, claiming someone is coming by about a job but really just planning to slurp highballs all day. Hamilton’s worm turns, and he hands over a bottle of whiskey spiked with castor oil. On his way to work he bumps into a pal who insists he mustn’t miss the afternoon’s big fight – and who does Hamilton the favor of calling his boss and getting him the day off by saying he’s all bereaved because his brother-in-law suddenly died. On his way to the fight, Hamilton offends enough traffic cops to get sent to the police station, while Claude gets sicker and sicker on the laced liquor. He finally gets to the fight just as it’s starting – and just after all the $10 seats are gone, so it costs him $15. But when he enters the arena, he meets a flood of exiting patrons: The bout was a one-punch knockout. He goes home to find the police ready to bust him again, this time for poisoning Claude. After confessing to putting castor oil in the booze – a revelation that sends Claude rushing high-speed to the thickest of forests – the police withdraw, the mother-in-law storms out of the house, and Hamilton enjoys a closing cuddle with Beebe.

Bruckman reworked this story into the Columbia two-reeler Andy Plays Hooky (1946) for Andy Clyde, where he was credited as writer; as will be discussed below, it was also the scenario for W.C. Fields’ Paramount feature Man on the Flying Trapeze (1935) – on which Bruckman was credited only as director. Too Many Highballs, his first run at this material, is admittedly a hurried and low-budget affair (especially when compared to the smarter-looking Hal Roach shorts of the day), but it still manages to be a lot of fun. Hamilton’s traffic trouble – expanded into W.C. Fields’ own Stations of the Cross in Trapeze – are here crisply conceived as a single scene of escalating mayhem. Hamilton skids on a wet street and glides past the cop who’s signaling him to stop. The cop gets on his running board and tells him to pull over to the curb, but as Hamilton changes lanes he collides with the same cop car he backed into just before – with a force that sends his uniformed passenger sprawling. When told by one of these angry cops to pull over, he lurches into a parked police motorcycle and topples it.

Playing the cop who’s been mad at Hamilton since the first collision is an unbilled Bud Jamison, a comedy veteran who had already worked with Chaplin, Langdon, and Lloyd, and who would soon find a way of life at Columbia playing opposite the Three Stooges. The burly comedian tears into this small role like a hungry dog devouring a steak. He steals every scene he’s in, whether he’s bullying Hamilton or just casually describing to another cop – with Hamilton sandwiched between them in the back of a police car – what happened to his previous collar: “We socked it to him. He just happened to be one of those guys that I don’t like.”

Jamison brings a lot more fun to Too Many Highballs than does Hamilton’s co-star Marjorie Beebe, who actually has very little to do; getting grossed out as she attends her ailing brother by giving him what else but castor oil is about the extent of her comic business. The real fun comes from comedian Tom Dugan as Claude. Resembling a more oaf-like Shemp Howard (yes, such things can be), Dugan groans to his mother between cramp seizures, “Get a cheap doctor!” When Beebe’s helping of castor oil hits home, he quietly informs her, “Oh yes. I’m feeling worse.” Best remembered today as the Polish actor who impersonates Hitler in Ernst Lubitsch’s classic To Be or Not To Be, Dugan also played uncredited roles in Harold Lloyd’s The Cat’s-Paw and Abbott & Costello’s In Society – two films co-scripted by an uncredited Bruckman.

Too Many Highballs was shot in either late December of 1932 or early January of ‘33, and released on February 10; The Fatal Glass of Beer was held back until March 3, even though Fields’ short had been ready since early December. Fields had completed the script back in November, while Bruckman was shooting The Human Fish; he derived this shaggy-dog lampoon of old-fashioned Temperance melodrama from his Frozen North skit “Stolen Bonds,” which Fields had performed in the 1928 Earl Carroll Vanities in New York. Static and zany at the same time, The Fatal Glass of Beer is unlike any other film Fields had done up to then – or just about any other sound comedy of its time. Although today revered, on its release the short mystified audiences and critics and was widely rejected. One Fields biographer noticed that Bruckman directed this film and commented, “Presumably Bruckman just sat behind the camera and laughed like crazy.” Yet even if that had been Bruckman’s entire contribution, how exceptional a situation it still would have been! Bruckman got the joke – and as Fields’ director he did what was needed to bring this eccentric, bizarre vision to life, the first great flowering of Fields’ love of the absurd.

Mack Sennett was one of the first not to get the joke, and he vetoed a reteaming of Fields and Bruckman. An angry and disappointed Fields reproached him for it in a letter dated December 7, 1932: “You are probably one hundred percent right, The Fatal Glass of Beer stinks. It’s lousy. But, I still think it’s good. You have turned sour on the new Bruckman story too. You thought both stories were good when you first heard them. So did I and am still of that opinion.” Fields asked to be let out of his contract in that letter, although in fact he stayed on to write and star in two more superb shorts for Sennett, The Pharmacist and The Barber Shop, both directed by Arthur Ripley. On December 9 Sennett was given the script of a two-reeler called His Perfect Day; although unsigned, this prototype of Man on the Flying Trapeze is plainly the work of Fields and Bruckman, a development of the story that Fields had defended to Sennett. Over the next week changes were spliced into that script, and on December 18 an unhappy Fields again wrote Sennett: “I worked on the last story ten full days to make it a story that would fit my style of work. You changed it to fit someone else, added an indelicate Castor Oil sequence, and sent it to me with the curt message, that if I did not like it in the changed form you would give it to Lloyd Hamilton.” Fields then left the project and Sennett brought in Hamilton. Bruckman stayed on to direct, but after that he took off: Watching Sennett stare down the end of his career must have reminded Bruckman of 1921, when he jumped Warners’ then-sinking ship to work with Keaton. Only this time, there was no one to catch him.

Almost all the majors – Fox, RKO, Paramount, Universal, Warner Bros. – were reeling during this Depression low point. After Sennett folded, a lot of talented people were caught short. The expert comedy director Del Lord, who’d helmed Ben Turpin, Billy Bevan, Andy Clyde, and others at Keystone in the ‘20s, became a used-car salesman on Ventura Boulevard. A jobless Lloyd Hamilton, wandering the streets of Hollywood, was arrested for public drunkenness just a few months after Too Many Highballs was released.

For almost two years, from early 1933 until the beginning of ‘35, there are no credits for Bruckman, although he’s known to have done uncredited-gagman work on two Fox releases of 1934. She Learned About Sailors was a romantic comedy starring Alice Faye and Lew Ayres, directed by George Marshall; Bruckman was probably brought in to punch up the hijinks of the acrobatic roughhousing duo, Frank Mitchell and Jack Durant. The other film was Harold Lloyd’s new project. Unhappy with the response to Movie Crazy, Lloyd hoped to please the public with more story and dialogue, and so for the first time he starred in an adaptation of a novel, Clarence Budington Kelland’s The Cat’s-Paw. He also played the lead relatively straight, refraining from a more-familiar Lloyd persona and the expected gags. Still, he covered his bets sufficiently to have Sam Taylor write and direct – his first work with Lloyd since their string of hits in the ‘20s. Lloyd also generously hired Bruckman to spend several months feeding laughs into the script. But very little of that work found its way onscreen, and the plot-heavy Cat’s-Paw was Lloyd’s first film to lose money.

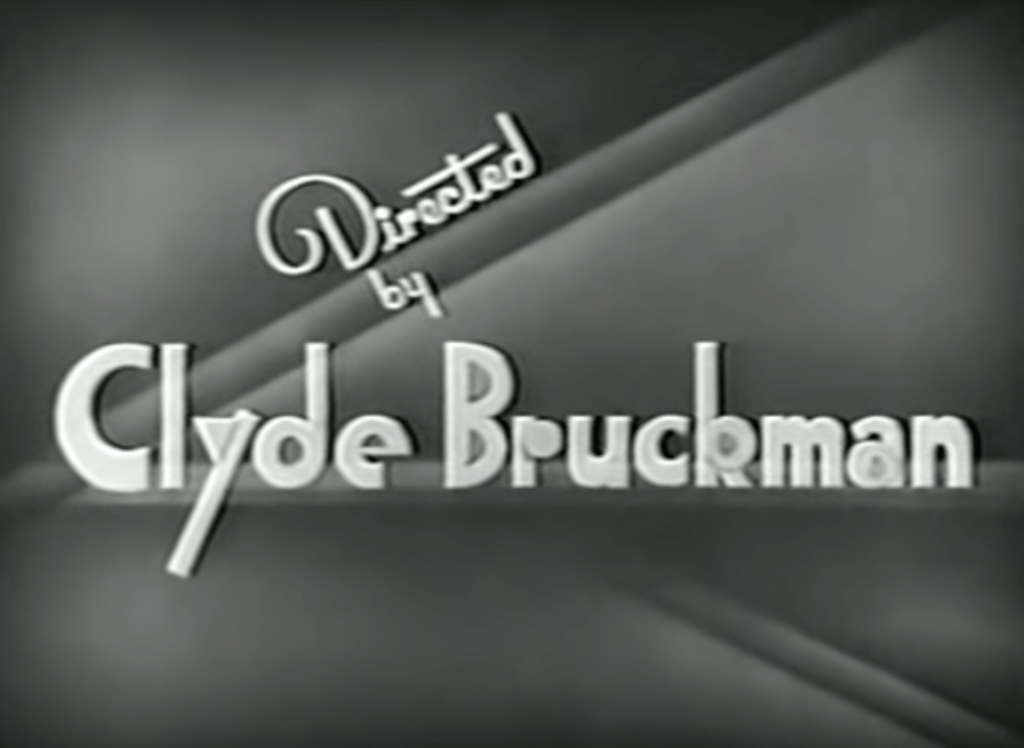

Bruckman, however, was once again directing by late in 1934, this time at Columbia. But he departed after helming only one two-reeler for the Three Stooges, their fifth short at Columbia: a Western parody called Horses’ Collars, scripted by Adler. (Two years later, Adler would rework the material as a writer on Laurel & Hardy’s classic feature Way Out West). Bruckman was of course right at home with Columbia and the Stooges, and by late 1935 he’d begin a 12-year stint as one of the studio’s writers. At this point in his career, however, he may have made Horses’ Collars more as a leg up to directing features, because he then went to Fox and helmed the 1935 release Spring Tonic, another hour-long piece of B fluff starring Lew Ayres, this time opposite Claire Trevor; ZaSu Pitts and Jack Haley provided the broader support. Bruckman’s next film as a director, however, turned out to be a classic: W.C. Fields’ Man on the Flying Trapeze.

Act III: Who was the man on the flying trapeze?

The common wisdom holds that Man on the Flying Trapeze is Fields’ remake of his 1927 silent feature Running Wild, directed and co-scripted by Gregory La Cava. A lost film for several decades, Running Wild eventually resurfaced and everyone saw that the two films’ stories are completely different; but the old belief continued to be repeated. In fact Man on the Flying Trapeze owes Running Wild little more than Fields’ characterization as a husband and father trapped in a nagging household. Story credit for Man on the Flying Trapeze went to Fields (under the name “Charles Bogle”) and his former vaudeville chum, the comic and writer Sam Hardy; the screenplay is credited to Hardy and Ray Harris. Nevertheless, the film takes its plot from Bruckman and Fields’ His Perfect Day script. This time, it’s the mother-in-law who is said to have died, and the brother-in-law is of course spared the castor oil. Otherwise it’s all there, from the non-breakfast with live-in in-laws and ditching work with a phony death in the family, to the gags with cars ‘n cops and missing the fight, down to such minor details as the brother-in-law named Claude and the $15 ticket; and of course the ending has in-laws quelled and happiness restored.

The first script of His Perfect Day had other anticipations of Man on the Flying Trapeze. Here, the home-sweet-home of Bill Snavely (the same surname as Fields’ character in The Fatal Glass of Beer) is blighted not just by his in-laws, the Shugs, but also by his tiresome, scolding wife. As in Trapeze, he does his own lying to the boss, and claims that his mother-in-law is no more. (“No more what?” asks Mr. Scroggins. “Just no more,” sez Bill. “She died!”) The second script, dated three days later (Dec. 12), has numerous chunks of pages directly from the first, along with several new scenes – including Sennett’s castor-oil gag. This script, however, also contains new material that further anticipates Man on the Flying Trapeze, most notably a classic set piece that would appear in both Too Many Highballs and Trapeze: Hamilton/Fields’ parked car is pinched tight on both ends, and when he tries to pull out he bumps the car behind him, riling its mean chauffeur. Having been warned not to back up too far, he never notices when the chauffeur’s party returns and the car drives away, leaving the rest of the block behind him empty. So he shimmies back and forth pointlessly until an obnoxious cop reacquaints him with reality, but when he backs up this time, he slams into a new car that’s just pulled in – and to cap the capper, it’s fulla cops!

Our protagonist’s woes proceed from there, as the story requires. In Too Many Highballs Hamilton gets sent to the station house and has some of his funniest business (including a sobriety test where he’s spun around in a chair and then made to walk a straight line). When Fields backs up, he collides with a police ambulance and jolts a gurney-bound patient right out its doors and off down the street, inflaming not only more cops but also the patient’s handbag-swinging sister. Bruckman got a lot of mileage from this automobile routine and reprised it with Buster Keaton in the 1939 Columbia two-reeler Nothing but Pleasure and in the 1953 Abbott & Costello television show “Car Trouble.”

The ending of the second script of His Perfect Day also wound up in Man on the Flying Trapeze, largely unaltered: To smooth over his unscheduled appearance back home, Snavely returns “with a little dinky bunch of violets in his hand” for the wife. Learning of the castor oil, Claude “makes a pass at Bill, but Bill ducks and counters with a punch on the jaw, which knocks Claude back onto the stretcher, out cold.” Mrs. Shug makes to hit him with her umbrella, and “Bill hauls back his fist as he says (defiantly) ‘Go on!’” She leaves in a huff, and when the men with the stretcher “carry Claude past Bill, he looks at him, then notices the wreath with the wording ‘Rest In Peace’ and picking it up he lays it on Claude’s chest as they carry him out.”

Judging from all the new material eventually destined for Trapeze, which appears in the castor-oil version of the script, Fields and Bruckman had plainly made an effort to accommodate Sennett’s bunkhouse humor – regardless of how unfunny the subject of tainted liquor may have struck either of them. But in the third draft, dated Dec. 17 – the day before Fields’ second miffed letter to Sennett and his decision to leave the film – Bill Snavely’s name has been changed to Harold Hobbs, the name used in Too Many Highballs. This version also has other gags which would be seen in that short, including the station-house scene and Claude’s closing sprint to the Great Outdoors (replacing the fisticuffs and the wreath). Curiously, a new joke in this script, which also appears in the film, suggests that Fields may still have been trying to keep his hand in: At breakfast Harold is given a foul-smelling egg that’s gone bad. He turns it away and his wife asks, “Shall I open the other one?” “No! Open the window,” he tells her. This same exchange can also be found in the first draft of Fields’ script for The Fatal Glass of Beer: a bit of business between Ma and Pa Snavely when they sit down for their meal, which never made it into the final version.

Ronald J. Fields, the comedian’s grandson, encouraged several misconceptions of how Man on the Flying Trapeze was made: “While searching for a suitable director, William LeBaron, W.C.’s friend and producer, temporarily took over the directing duties, but then he caught a severe cold and had to quit. Clyde Bruckman […] replaced LeBaron, but he too caught a severe case of influenza and had to leave for a couple of weeks, so Sam Hardy and W.C. grabbed the helm and directed the picture until Bruckman returned.” However, on March 20, 1935, Variety reported, “Paramount signed Clyde Bruckman to direct W.C. Fields in his next picture. Will be titled The Flying Trapeze.” In fact Bruckman was one of the first people on the film, hired as director back on March 15 – which meant keeping him on salary for six weeks before the start of shooting on April 27. And when it started, Bruckman was directing: The Hollywood Reporter of April 26 noted that the film would “get shooting tomorrow under the tentative title Everything Happens at Once. W.C. Fields stars under Clyde Bruckman’s direction”; two days later, its “Pictures Now Shooting” column reported both the film and its director.

The 34 shooting days of Man on the Flying Trapeze are documented in Paramount’s Production Dept. Control Sheet for Prod. #1047. In the “Delay” column Bruckman’s name is cited twice: On April 29, the second day of shooting, his lateness is part of an unspecified delay time that’s also attributed to story work and rushes; on May 13, one hour and 20 minutes are lost because “Bruckman ill.” The trade papers noted that illness. “W.C. Fields took over the direction of his untitled picture at Paramount when flu sent Clyde Bruckman home,” said the May 15 Variety. “Sam Hardy is assisting Fields, both keeping picture going rather than lay off the troupe.” The Hollywood Reporter on the 14th ran an item titled “Bill Fields Doubles as Director at Para.”: “W.C. Fields was his own director with the help of Sam Hardy, comedy constructor, in Everything Happens at Once on the Paramount lot yesterday. Illnesses of both producer William LeBaron and director Clyde Bruckman made the megaphone available. Neither producer nor director was reported seriously ill.”

Of Paramount’s surviving Retake Request forms for the film, eleven are signed by Bruckman; all are undated except one marked May 22 – only eight working days after he’d taken ill on the 13th. There is no information in the film’s remaining papers as to anyone else taking over as director. Fields and Hardy most likely did fill in for Bruckman as was reported, but they certainly didn’t do it for very long, or else there’d have been some production documentation or further press coverage. The notion that Fields could have directed the film for weeks, even with Hardy, seems less plausible considering that the Control Sheet cites Fields on nine different occasions for causing delays due to lateness and/or illness, most often during the second half of the shoot, after May 13. His unavailability cost the production well over 14 hours – the equivalent of one full shooting day wasted – and one can detect an undercurrent of criticism against the comedian in The Hollywood Reporter article of June 7, headlined “Bruckman Sets Record”: “Clyde Bruckman set a record at Paramount yesterday when he brought in Everything Happens at Once, the W.C. Fields picture, a day under schedule. Usually the Fields productions run over.” The credit given Bruckman was just, and the production notes of Paramount’s Unit Manager Harold Schwarz include a June 6 citation regarding a saving of $2,600 in the cost of “direction – gain in schedule and eliminating cutting time of director.” Ironically, two weeks later Schwarz would have to give the surplus to Bruckman anyway, because the saving of the 6th was offset by the cost of rehiring him to shoot two more days of retakes, on June 18 and 21.

Beyond family legends and the sheer laziness of the many hack biographers in the cottage industry of Fieldsiana, the legend of W.C. Fields as the secret director of Man on the Flying Trapeze has tended to linger because Paramount’s publicity department played up the story in its 1935 Press Sheets. According to a July 26 article entitled “Fields Cures Odd Complex As Director,” the comedian was possessed of an “inferiority complex” occasioned in a Ziegfeld show, after being admonished that he’d never be a good director. His cure was “a slight cold. The cold was not his, but Clyde Bruckman’s, director of the comedian’s newest film, Man on the Flying Trapeze […] One day Bruckman retired sneezing from the set at Paramount, and Fields, stepping nobly into the breach, directed the scene himself.” Another July 26 item, “Comic Turns Director For A Day – Fields Asks Title For New Duties,” alludes to “the brief illness of Clyde Bruckman, director. In his absence, the directorial duties were assumed, with flourishes, by Fields and Sam Hardy, ex-actor, now writing dialogue. While Fields and Hardy agreed that they were co-directors, neither wanted to be ‘top hand.’”

Other than the proof of Bruckman’s presence on the set by May 22, the only documentation yet recovered as to the duration of his absence is the following piece from The Hollywood Reporter of June 17 – and it too smacks of the press release, right from its title, “Sam Hardy A Pooh Bah On Fields Production”: “Sam Hardy had to call all his versatility into play during the making of Man on the Flying Trapeze, at Paramount. Hardy worked with Charles Bogle on the story, was comedy constructionist throughout, and even directed for a few days when Clyde Bruckman was ill.” Of course, if Hardy had called all his versatility into play, he’d have also acted in the film rather than kept behind the camera. (He’s probably most familiar today from King Kong, uttering the film’s first line as the theatrical agent who can’t produce a girl for Carl Denham’s mysterious voyage.) That oversight not withstanding, this contemporary estimate of “a few days” falls within seven and is most probably accurate.

On June 12, The Hollywood Reporter noted that Paramount had restored the title Man on the Flying Trapeze to Fields’ film, and added, “Fields also persuaded the studio yesterday to credit Sam Hardy as co-author of the story with Charles Bogle (i.e., W.C. Fields).” Such lobbying was a true act of generosity on Fields’ part, considering Hardy would also get a co-screenplay credit with Ray Harris – and that the actual story credit for Man on the Flying Trapeze belonged to Fields and Bruckman, the writers of His Perfect Day. In fact, more than these four contributed to Trapeze: LeBaron and Fields had been hiring people to work on the screenplay since February. By March 15, when Bruckman signed on, Jack Cunningham had already spent over four weeks on rewrites and had been replaced by Bobby Vernon, who stayed with the script until mid-April; Ray Harris came on board near the end of March. Sam Hardy, however, was brought in shortly after shooting began, along with writer John W. Sinclair. (Essential cast members such as Mary Brian and Grady Sutton were also signed during production.) Paramount’s earliest surviving script draft is dated April 22, a week before Hardy started working on the film, and by then the story was already in place. What still required developing was Fields’ profession as a memory expert: There’s no secretary Carlotta, no rolltop desk jammed with inscrutably organized papers – instead, the script has Fields sending a clerk to retrieve an obscure file which he recalls being in Section 4, Row 3-A, Cabinet 7, Compartment 6, Folder XXX, Envelope 33-62-44-2! The relationship with his daughter Hope is also thinly drawn; in this script, it is Fields, not Hope, who renegotiates his salary and perks with his former employers when they try to rehire him.

With the arrival of Hardy and Sinclair, the filming of Trapeze was frequently stalled by problems with the script – after Fields himself, the production’s greatest source of delay. The Control Sheet has ten entries, almost all in the first 20 days of the shoot, which note work being halted for story conferences and rewrites, with hours lost “waiting for script” or because there was “no script.” The notion of Bruckman not working on the script, either in the weeks prior to shooting or in rewrites on the set, is untenable – especially because the basis of the film is his story which he’d developed with Fields less than three years before. Four of the ten script-delay citations occur between May 13 and 21, when Bruckman was unavailable, which only strengthens the suspicion that his signing as director well in advance of production was a move to bring another writer onboard as soon as possible. Bruckman got a sweet deal too: a contract guaranteeing him a pay hike after the first ten weeks, from $900 per week to $1000, which means he actually received a raise during the shooting. The extra money may also have been intended as compensation for his once again being an uncredited writer.

Further gratitude can be read in the credit that Bruckman did receive. Man on the Flying Trapeze opens with a veritable sardine can of a title card, cramming the film’s lengthy moniker together with the names of Fields, LeBaron, studio president Adolph Zukor, and even actress Mary Brian. The second title, however, reads only, “Directed by Clyde Bruckman,” in jaunty Art Deco letters that outsize everything else, even the type used for Fields’ name or the film’s title. Such a nod was hardly business as usual for a W.C. Fields comedy: Look at director Norman McLeod sharing the screen with producer LeBaron on their credits for the previous year’s It’s a Gift. And for a director who a year earlier couldn’t get a job, this kind of credit definitely wasn’t business as usual. Size does matter, as the saying goes, especially if this director didn’t direct the entire film – instead of saying he wrote some of it and directed most of it, let’s just say he directed all of it, and say it REAL LOUD TOO!

As part of its expansion to feature length, Man on the Flying Trapeze attaches to the Perfect Day scenario an opening 20-minute sequence that offers one of Fields’ sharpest lampoons of the hell of middle-class domesticity – a favorite target of his while at Sennett. Unlike his more familiar persona of a larger-than-life grifter, the stammering, confused Ambrose Wolfinger is Fields at his most defeated and ineffectual. This man is clearly in a desperate situation, taking furtive sips of secret applejack while hiding in the bathroom and abrading the side of the medicine chest with his toothbrush to provide audible proof that he’s only brushing his teeth in there. Small wonder that, when his pistol accidentally discharges and breaks a window, causing his wife to swoon, one hears more than a tinge of hope in his voice when he asks, “Did I kill you?”

Ambrose and Henrietta (Kathleen Howard) take to their separate beds only to be roused by two burglars (one of whom is played by a young Walter Brennan). Having broken into Wolfinger’s cellar, they become noisily drunk on his applejack. A cop arrests the crooks and brings along Ambrose as a witness, with some of the applejack as evidence; but as soon as it’s produced in court, the judge asks Wolfinger if he has a license to manufacture alcohol – and has him locked up when he admits he doesn’t. The entire opening sequence can easily stand on its own as an expert two-reeler, and suggests the kind of work Fields and Bruckman could have made for Sennett had he given them more money and refrained from interfering with them.

Another important addition made by Man on the Flying Trapeze to the His Perfect Day scenario is the role of Ambrose’s grown daughter Hope, the child of his first marriage. She’s derived from Fields’ silent Running Wild, in which her character was named Elizabeth. Her function, however, is the same: to play a sympathetic role in her father’s struggles with his second wife and her nasty family – although in the silent, the only in-law bedeviling Fields is a boy, his wife’s young son, not the classic mother-in-law/brother-in-law tag team which Man on the Flying Trapeze reprises from His Perfect Day. Mary Brian played Elizabeth as well as Hope, and with both films having been William LeBaron productions at Paramount, confusions arose as to the long-unseen Running Wild being the basis for Trapeze. The Elizabeth/Hope character was a congenial device for Fields, who throughout his career preferred the less sexual, more sentimental and sympathy-building father/daughter relationship to the head-on husbandry that Lloyd Hamilton offered Marjorie Beebe in Too Many Highballs – a preference that also resulted in Fields enjoying onscreen snuggles with many young lovelies rather than with the Kathleen Howards and Alison Skipworths and Margaret Dumonts assigned to his side.

Trapeze further expands His Perfect Day by developing the professional life of Fields’ character, which also provides a rich vein of social satire. Ambrose is of course just as mistreated by the blowhards and backstabbers in his office as he is by his wife and in-laws, and thus is totally ignorant of the fact that he occupies an invaluable position in his firm. The weird premise of W.C. Fields as a memory expert does grab the imagination, and in England the film was released as The Memory Expert, even though there’s only one scene of Wolfinger at work performing his instant recall. Still, it is one unforgettable scene, with his recitation of business info on the Australian sheepman J. Farnsworth Wallaby, which includes such humanizing addenda as, “He has two boys. One is a champion tennis player, and the other one is a manly little fellow.” (Fields and Sam Hardy in fact used to spend hours playing tennis on Fields’ personal court.) The memory-expert device was necessary to pave the way to Fields’ triumph at the end of the film: After Wolfinger is fired for telling a fib and sneaking off to the fights, his boss can no longer retrieve the firm’s information and so must rehire him at exorbitant terms. Reversals of fortune occur throughout Fields’ films, from the oil-well stock that suddenly pays off in 1927’s The Potters to the beefsteak-mine stock that suddenly pays off in 1940’s The Bank Dick; but in Man on the Flying Trapeze, Fields actually earns the success he unexpectedly gets to enjoy. It’s easy to see in this anomaly a Bruckman wish projection: the essential component being reinstalled – you have to keep me on, despite my derelictions, because you need my unique services.

The film’s closing gag, which defines Wolfinger’s unexpected ascendancy and appears in the April 22nd draft, also suggests Bruckman’s hand. Ambrose is out for a drive in the new car paid for by his gargantuan raise, with his wife and daughter alongside him in the front and only seat. His in-laws are in the rumble seat, and when a sudden downpour erupts they get an epic drenching – only now they’re too timid to murmur a word against Ambrose, who remains dry and content behind the wheel, driving leisurely and enjoying his sandwiches and thermos of coffee. This finale recalls a painfully funny scene in Keaton’s The Cameraman, which Bruckman co-scripted: Buster and his girlfriend get a lift from his rival, but there’s room inside only for her and the driver, and so it is Buster who gets rumbled and soaked.

Man on the Flying Trapeze today is cherished as one of Fields’ best films, but it opened to mostly negative reviews. “[A] very bad, if not hopeless comedy concoction,” carped Variety. “Hard work of Clyde Bruckman to get anything intelligent out of what he had proved of no avail.” In light of its lukewarm reception, Fields’ special efforts to promote Sam Hardy in the press and with the studio seem all the more pointless – darkly ironic too, considering that Hardy died less than three months after the film’s release, stricken suddenly with an abdominal ailment. By then Fields himself was too ill to attend his friend’s funeral: Ravaged by decades of heavy drinking, his health had deteriorated badly, as indicated by his progressive unavailabilities while making Trapeze. Soon after wrapping the film, he had to dry out at the Soboba Hot Springs, a spa in the mountains of San Bernardino, Bruckman’s hometown.

Fields needed almost a year before he could recover sufficiently to star in Paramount’s 1937 release Poppy, and even then he was still so shaky that the film was rewritten to develop the secondary characters, while his own scenes were curtailed and shot with the extensive use of a double (none other than John W. Sinclair, the writer hired along with Sam Hardy on Trapeze). A further illness, complicated with pneumonia, hit Fields after Poppy, and kept him offscreen – despite his dual role – for much of The Big Broadcast of 1938, his last film for Paramount.

That studio had made Fields a star in silent features, but was skittish about him in talking pictures – the medium that freed his comic genius and brought him immortality! Paramount made Fields prove himself all over again, casting him in early talkies that billed him prominently but didn’t give him a lot of screen time. He’d made the Sennett shorts to demonstrate his own star wattage, yet Paramount sent him back into the same type of feature roles as before, using him as a supporting player in his own films. There were two exceptions in 1934, The Old-Fashioned Way and It’s a Gift. Man on the Flying Trapeze was his third and last such comedy of the decade. Only after his health stabilized and he signed with Universal would Fields find his apotheosis starring in his final 1940s comedies, The Bank Dick and Never Give a Sucker an Even Break.

Lloyd Hamilton’s drinking had cost him his life back in January of 1935, when he suffered a massive hemorrhage from a ruptured ulcer. That same year, not long after Fields’ health crisis began, Bruckman saw Buster Keaton institutionalized for dipsomania. The talkies Keaton had made at MGM were more profitable than any of his silents had been, but eventually he chose to stay away and drink rather than perform the material he was given. After the studio fired him in January of 1933, Keaton never again starred in a Hollywood feature. Acting in cheap European films and even cheaper shorts for Educational eventually sent him on one of his worst binges, until he was placed in the Veterans Hospital at Sawtelle, near Los Angeles. He re-emerged two weeks later, went back to work at Educational, and remained sober for the rest of the decade. Around this time, Bruckman too seems to have reached a new balance in his life, considering how productive a writer he became in the late 1930s and early ‘40s – after his retirement from directing with Man on the Flying Trapeze.

Directing may well have exacerbated Bruckman’s drinking – the pressures of that job could have been too much for him, especially the more costly and controlled productions in sound. It’s possible, therefore, that Man on the Flying Trapeze wasn’t the last directing job Bruckman could get, but rather the last one he’d take, in an effort to quit drinking, or at least to regain control of his life. Writing two-reelers at Columbia was a step down as far as money and prestige were concerned; but if Bruckman had given up directing to save his soul, his sacrifice seems to have been accepted, because he was brought to another creative plateau.

Act IV: The germ of the ocean

In 1920 Harry Cohn, Joe Brandt, and Harry’s brother Jack united to form the C.B.C. Film Sales Company – dubbed “Corned Beef & Cabbage” by wags unimpressed at the small studio’s low-budget output. When the company was renamed Columbia Pictures in 1924, “The Germ of the Ocean” became the new putdown for the studio. But each year saw more feature releases, especially after Cohn hired director Frank Capra in 1928. By 1934 producer/director Jules White was running Columbia’s short-films department, and among the talent he signed up in 1934-35 alone were the Three Stooges, Harry Langdon, Andy Clyde, Arthur Ripley, Felix Adler, Del Lord – and Clyde Bruckman.

The world of Columbia Pictures’ two-reelers, in all its vitality, violence, and vulgarity, was a true Rome to the Athens of silent comedy. Between 1935 and ‘37 Bruckman worked on some great Three Stooges shorts, when Moe Howard, Larry Fine, and above all Curly Howard (Moe’s brother) were at their wildest. Among his gems for them are Three Little Beers (1935), where the Stooges run amok on a golf course, and the wrestling send-up Grips, Grunts, and Groans (1937).

But in 1938 Bruckman stepped away from Columbia and returned to features, working for the last time with Harold Lloyd. Realizing the weakness of the script for Professor Beware, Lloyd brought in Bruckman, but this offbeat chase film was a lost cause; each man had turned to the other, hoping to jump-start his career, and both were let down. After the failure of Professor Beware, Bruckman went back to two-reelers at Columbia and Lloyd retired from performing (until Preston Sturges coaxed him back for a final bow). By then, Buster Keaton was also gone from the screen, working offcamera at MGM as a gagman. When Bruckman returned to Columbia, he brought Keaton along, and Jules White signed him to a series of shorts. Although reteamed for the first time in a decade – Bruckman worked on most of Keaton’s ten short films, including the highly regarded Pest from the West (1939) and Pardon My Berth Marks (1940) – the old fires were seldom rekindled. Keaton hated working at Columbia and was glad to leave in 1941. He’d also begun drinking again.

Bruckman, unlike Keaton, thrived at Columbia, writing or co-scripting more than thirty shorts directed by White. Justly beloved are his Three Stooges classics of the era: Three Sappy People (1939), with the Stooges infiltrating high society; their lampoons of Hitler and his cohorts, You Nazty Spy! (1940) and I’ll Never Heil Again (1941); the pie-throwing marathon In the Sweet Pie and Pie (1941); and Dizzy Pilots (1943), an aviation saga in which Moe is inflated and floated. He also wrote funny scripts for other Columbia stars, such as Andy Clyde Gets Spring Chicken (1939), an Andy Hardy send-up for hayseed Andy Clyde, and the role-reversal farce Pitchin’ in the Kitchen (1943), first in the series starring lovable “woo-woo” comic Hugh Herbert. A dozen of Bruckman’s films for White were co-written with Felix Adler, who’d last worked with Bruckman on Lloyd’s early talkies. Their final script together, Tireman, Spare My Tires (1942), was for Harry Langdon – the star of the first short on which the two writers had both worked, back in 1925. Not surprisingly, Langdon’s brand of comedy was even more elusive at Columbia than Keaton’s had been, even though, like Keaton, Langdon was reunited with former colleagues (in his case, Ripley and Edwards). Since 1934 Langdon had made ten shorts at the studio; in the next two years he’d make another ten, including the indifferent A Blitz on the Fritz (1943) with White and Bruckman, until 1944 and his death at the age of 60 from a cerebral hemorrhage.

Late in 1941, Bruckman worked on the story for the Columbia B picture Blondie Goes to College (1942), the tenth outing in the studio’s series based on Chic Young’s comic strip. His script collaborator was Warren Wilson, and when Wilson began producing B films at Universal the following year, he got Bruckman to write the quickie musical Honeymoon Lodge (1943) for radio (and later, television) stars Ozzie and Harriet Nelson; the laughs went to Franklin Pangborn, as they had with The Human Fish. Soon Bruckman was on board at Universal, where for two years he scripted or co-wrote six more Bs for Wilson. Swingtime Johnny (1943) reunited him with director Eddie Cline, although that meant a good deal less when the film starred the Andrews Sisters instead of Buster Keaton. Like the other Wilson films that Bruckman wrote – Week-end Pass (1944), Twilight on the Prairie (1944), Under Western Skies (1945), Her Lucky Night (1945) – Swingtime Johnny was the digestible and forgettable hour-long fodder it was intended to be. So were So’s Your Uncle (1943), Moon Over Las Vegas (1944), and South of Dixie (1944), all co-scripted by Bruckman for producer/director Jean Yarbrough, who’d also helmed three of the Wilson films.

There were two bright spots. The Wilson production She Gets Her Man (1945) was a funny mystery satire that teamed veteran funnyman Leon Errol with the delightful comedian Joan Davis; In Society (1944) was Bud Abbott and Lou Costello’s tenth starring feature at Universal. It was also Yarbrough’s first time directing the duo, so he brought in Bruckman as an uncredited gagman. Yarbrough would helm four more Abbott & Costello films and, a decade later, direct them on television – that’s when Yarbrough gave Bruckman his last job. In the movie industry he had become a non-person after Harold Lloyd learned about some of the gags that turned up in She Gets Her Man.

Lloyd was not amused by So’s Your Uncle and its recyclings from Movie Crazy; when two more came out some 14 months later, the shit hit the fan. She Gets Her Man got its laughs off For Heaven’s Sake and Welcome Danger, and Her Lucky Night had been equally intimate with The Freshman, so Lloyd slapped Universal with a trio of lawsuits.

For Bruckman still to have been kept on at Columbia is a tribute to the loyalty of Jules White – who quickly handed him off to director Edward Bernds, probably because Bruckman’s drinking got worse as the litigation wore on. Then, early in 1946, the Harold Lloyd Corporation sued Columbia over the 1942 Three Stooges shorts Loco Boy Makes Good and Three Smart Saps, with Bruckman’s borrowings from Movie Crazy and The Freshman, respectively.

By 1947 Bruckman must have been Dead Man Walking at the studio, yet he scripted a dozen shorts during his last stint there. How much writing he could actually do then, however, is unclear. “The scripts were very sloppy,” Bernds later complained. “I would frequently have to revise his work, as there were so many unconnected pieces. Some of his scripts were totally incomprehensible.” Bernds plainly got something from Bruckman even then, because a lot of the shorts they made together are among their stars’ funniest, starting in 1946 with Hugh Herbert’s Honeymoon Blues, Andy Clyde’s Andy Plays Hooky, and the Three Stooges’ Three Little Pirates – easily the team’s best release that year.

The Stooges had made almost a hundred two-reelers in 12 years, and the wear had begun to show, with Curly becoming more sluggish and detached. He suffered a stroke during the shooting of their next film after Three Little Pirates and had to retire; six years later he died at age 48. Yet the Three Stooges were onscreen again by 1947, starting with the Bruckman-scripted Fright Night – originally intended for Curly, but Shemp Howard made the material his own. Like his brothers Moe and Curly, Shemp was a born clown. He’d appeared in short and feature comedies for years, and under Bernds’ direction the veteran comics rallied. Bruckman’s first films with them that year are among their finest, especially the cowboy spoof Out West and Brideless Groom, a two-reel reinvention of Seven Chances.

Bruckman also wrote a pair of memorable “scare” comedies for Hugh Herbert and director Del Lord, Nervous Shakedown (1947) and Tall, Dark and Gruesome (1948). The latter is slapstick by way of Edgar Allan Poe, with Hugh Herbert being shaved by a razor-wielding gorilla. The image typifies Columbia’s brand of lunacy at its best, and Tall, Dark and Gruesome was one of the studio’s most popular releases of the year. It was also the last release of a film written by Clyde Bruckman. In 1947 Lloyd won all his suits against both Columbia and Universal, and Bruckman became unemployable in Hollywood.

Act V: La commedia è finita

Drink apparently was Bruckman’s solace. Buster Keaton tried to help, but the gesture was even more futile than Bruckman’s ill-fated attempt to set up Keaton at Columbia. In 1950 Bruckman was hired to write for “The Buster Keaton Show,” a taped half-hour television series on Los Angeles’ KTTV. His job was mostly to create introductions for Keaton’s routines, but by then he was so steeped in alcohol that he couldn’t always handle even those minor assignments. Still, judging from one episode in which Buster is shaved by yes a gorilla, Bruckman must have risen to at least some of the series’ occasions.

Bruckman’s name appears onscreen in 1952, as the writer of Hugh Herbert’s last two-reeler The Gink at the Sink (the comedian’s last film role; he passed away that same year). Columbia had tightened its belt as the market for shorts steadily dried up, so Jules White was remaking his stars’ earlier films by shooting a few new scenes and cutting them together with footage from the originals. He’d sent Herbert back through his paces from the Bruckman-scripted Pitchin’ in the Kitchen, and so Bruckman was required by law to receive a script credit on this short too.

Thus, the next year Bruckman gets credited on the Three Stooges’ Up in Daisy’s Penthouse and Goof on the Roof, and Andy Clyde’s Love’s A-Poppin. A lot more meaningful, however, is his television writing in 1953. Making a remarkable comeback, Bruckman wrote several first-rate scripts for the CBS series “The Abbott & Costello Show.” The producer/director was Jean Yarbrough, his associate from Universal, and together they shared the last creative high of Bruckman’s career. Filming on the Hal Roach lot, Bud and Lou were in effect making two-reelers, which suited them perfectly. Their features, even the funniest, are padded with songs and romantic subplots; television distilled the team, offering polished versions of their classic routines along with a streak of surreal humor well beyond any of their films. Yarbrough brought in Bruckman for the second season, after retooling the show and scaling back the zaniness in favor of more-narrative episodes. That decision let down some fans, but what’s funny in season two is extremely funny. Any of the show’s episodes from either season would yield more laughs than their laborious Universal features of the same vintage: Lost in Alaska (1952), Abbott & Costello Go to Mars (1953), Abbott & Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1954). After three more, Bud and Lou would split in 1957.

The last episode of “The Abbott & Costello Show” aired in June of 1954, the same month that Columbia released two more White remilkings of Bruckman scripts, the Three Stooges’ Pals and Gals and Andy Clyde’s Two April Fools. By then Bruckman had to have been broke and desperate; by January of 1955 he was at the end of his rope. He went to beg Jules White for a job, but White was finishing his series and had nothing available. “I found a note when I came in the next morning to call Buster’s wife,” White later recounted. “Clyde had borrowed Buster Keaton’s revolver, gone into the men’s room of the saloon where he kept drinking, and blew his head off.” The Los Angeles Times reported that Bruckman had left a typewritten note in which he requested to have his body delivered either to the Los Angeles County Medical Association or to a medical school for experimentation, explaining, “I have no money to pay for a funeral.” As it turned out, Buster Keaton, whose .45 automatic Bruckman had used to take his own life, paid for the service.

That September another of White’s reworkings of a Bruckman script was released, the Three Stooges’ Wham Bam Slam; on January 5, 1956, one year and one day after Bruckman’s death, came the last: Husbands Beware, in which Moe, Larry, and Shemp retrace their way through Brideless Groom. Shemp had died of a heart attack the previous November, but Columbia would release seven more Stooges shorts that year. White made the last four after Shemp’s death, filming with a stand-in and adding old footage.

Epilogue

To tailor gags so they can fit one particular comedian’s style is a hard thing to do – for Bruckman to have done it for so many people, whose styles were so different, is exceptional. Consider that Buster Keaton, the creator of some of the funniest gags in the history of film, met mostly with disappointment when he worked as a gagman at MGM. In his autobiography he mentioned how he “failed to click” with both Abbott & Costello and the Marx Brothers; and although Keaton enjoyed an amicable rapport with Laurel & Hardy on their penultimate American feature, Nothing but Trouble (1944), the results were dismal. Only later in the decade, when Keaton’s own vehicles were remade for Red Skelton, did he find real success at the job of making someone else funny.

Yet some revisionist film histories have been dismissive of Bruckman; one even questioned “whether he was ever the great comedy writer many film historians claim he was. […] For all the comedies Bruckman either wrote or directed, there is no definite style or ‘typical Bruckman gag’ one can point to as an example of his work.” But the challenge to find a “typical Bruckman gag” is essentially a fool’s game. Instead, there’s a compelling argument for the belief that Buster Keaton never used a Bruckman gag. What good was a Bruckman gag to Keaton? He needed Keaton gags. And by working with Bruckman, Keaton got them, and his work was the better for it. Exactly the same could be said of Arbuckle or Lloyd or Langdon or Laurel & Hardy or Fields or the Three Stooges or Abbott & Costello.

Comedians don’t rely on a writer or a director because they need someone who’s like funny spackle, filling up holes with gags. They need someone who’s like a flint, to spark ideas; a touchstone, to reveal something genuine. For all of these hard-working professionals to take dollars out of their pockets and put them into Bruckman’s pocket, and keep on doing it for decades, should be taken seriously as evidence that the man was making a valuable contribution to those professionals’ hard work.

That a talent so multi-faceted as Bruckman’s should be tarred with borrowing is the saddest irony of all. The dearth of similar lawsuits in ordinarily litigious Hollywood suggests that most people within the comedy industry have understood that everybody borrows from everybody – including from one’s own work. Regarding Keaton’s KTTV series, biographer Tom Dardis wrote, “Buster made it clear that he had no intention of providing new gags for the shows. He believed that he had developed a more than adequate repertoire of gags over the years and saw no need for creating new material.” A similar attitude of availability, a shared need to hone and refine and redevelop, runs through the careers of Laurel & Hardy, Fields, Langdon, Lloyd, the Three Stooges, Abbott & Costello, and just about everyone else who earned a living by making people laugh. It’s no surprise that Bruckman wrote two-reel versions of Man on the Flying Trapeze and Seven Chances during his last stay at Columbia, even when he was being hauled into court and accused of plagiarism. He was a professional doing his job, just as his peers would do.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance and encouragement of film historians Rudolph Grey, Kevin Lally, and Leonard Maltin, and the expertise of Barbara Hall and the staff at the Margaret Herrick Library. Special thanks go to film scholar and author Joe Adamson for all his help and support.

(This essay, written mostly in 2003, appears here for the first time.)

SOURCES

Prologue

“a first-rate comedy man”

William K. Everson, The Art of W.C. Fields. New York: Bonanza Books, 1967, p. 86.

“one of the best gag men”

Kevin Brownlow, The Parade’s Gone By…. New York: Ballantine Books, 1968, p. 554.

“one of the all-time great”

Leonard Maltin, Selected Short Subjects. New York: Da Capo, 1972, p. 6.

“one of the key figures”

Kenneth Anger, Hollywood Babylon II. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1984, p. 218.

Act I

“Warners at that time”

Rudi Blesh, Keaton. New York: Collier Books, 1971, p. 148.

“Why Metro continues to feature”

anonymous, Harrison’s Reports, 03/17/23.

“Next to Miss Dana’s acting”

anonymous, Variety, 08/30/23.

Act II

“I got one of the gag men”

Harold Lloyd, An American Comedy. New York: Dover Publications, 1971, p. 131.

“Presumably Bruckman”

Simon Louvish, The Man on the Flying Trapeze: The Life and Times of W.C. Fields. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997, p. 392.

“You are probably one hundred percent right”

“I worked on the last story”

W.C. Fields by Himself. Ronald J. Fields, ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1973, p. 269.

Act III

“While searching for a suitable director”

Ronald J. Fields, W.C. Fields: A Life on Film. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984, p. 174.

“very bad, if not hopeless comedy concoction,”

anonymous, Variety, 06/26/35.

Act IV

“The scripts were very sloppy”

Ted Okuda with Edward Watz, The Columbia Comedy Shorts. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 1986, p. 32.

Act V

“I found a note”

David N. Bruskin, The White Brothers: Jack, Jules, & Sam White (The Directors Guild of America Oral History Series #10). Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1990, pp. 227–228.

“I have no money to pay for a funeral”

Los Angeles Times, 01/05/55.

Epilogue

“failed to click”