Michael Reeves and the Witches

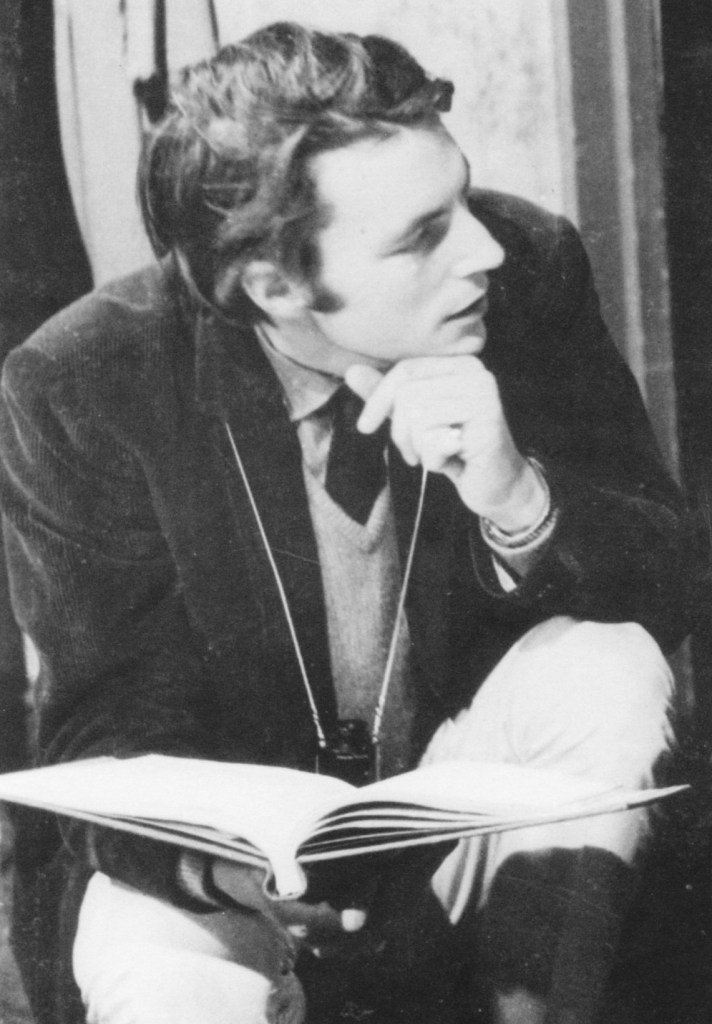

If he were still alive, Michael Reeves would now be preparing to celebrate his 80th birthday in October of 2023. Such a possibility, however, borders on the inconceivable, so difficult is it to imagine Michael Reeves being old. Having died in 1969 at the age of 25, he retains a perpetual youth in the minds of his many admirers – a youthfulness reinforced by the originality and energy of the three horror films he directed and co-scripted: The She Beast (1966), The Sorcerers (1967), and Witchfinder General (1968). That last title was initially changed to The Conqueror Worm for distribution in the United States, but after the film made its profound international impact, it has come to be known even here under its original name.

As if to signal the importance of his stature in British cinema, each of Reeves’ horror films features a true icon of the genre. Barbara Steele – unforgettable in such classic chillers as Mario Bava’s demonic Black Sunday and Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptation The Pit and the Pendulum – portrays the young bride who is possessed by a 200-year-old witch in The She Beast. Boris Karloff had one of his last and most memorable roles in The Sorcerers, playing an elderly scientist who, along with his increasingly deranged wife, is able to control a young man’s mind and actions while experiencing all his sensations, psychological and physical – including the thrills of murder. Vincent Price, as the 17th-century witch hunter of Witchfinder General, delivered what is universally recognized as his finest performance, devoid of sympathy or camp, making real the murdering hypocrite Matthew Hopkins, who mouths pieties as he leaves a trail of rape, torture, and death.

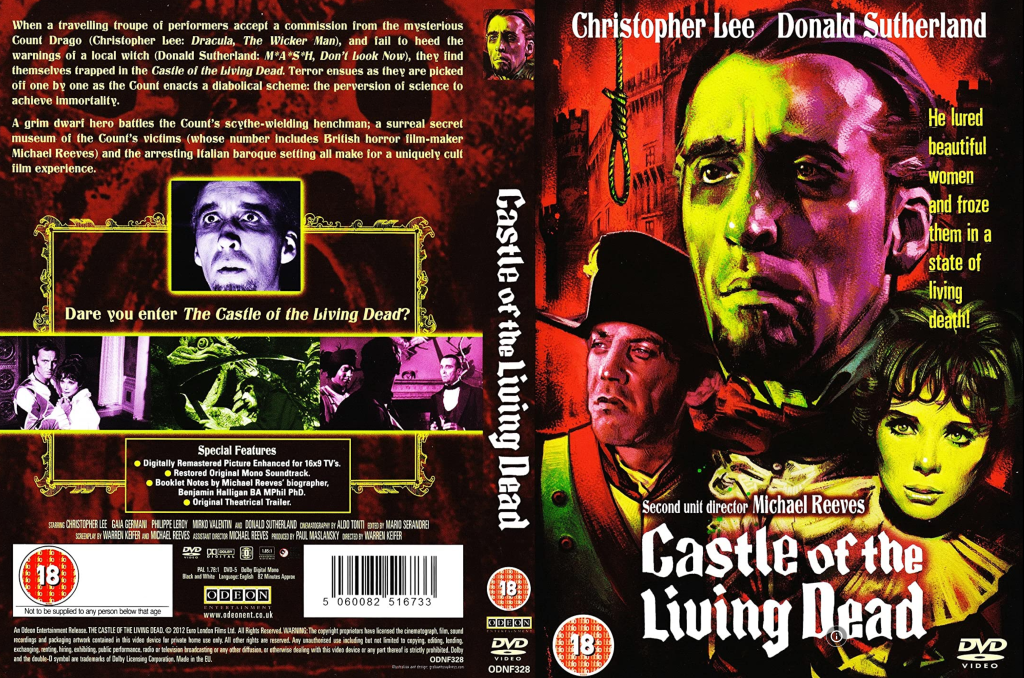

Uniting all of Reeves’ films is the recurring specter of the witch. Who she is and what she does may vary widely, but her presence was always with him, an archetype that had autobiographical as well as artistic meaning for him. The witch even appears in an earlier film, The Castle of the Living Dead (1964), on which he was an assistant director. This Italian-French co-production has come to be regarded as the prologue to Reeves’ career, and it too stars one of the great horror-genre actors: Christopher Lee plays Count Drago, an early 19th-century scientist whose formula paralyzes and kills his specimens – both animal and human – while preserving their bodies in an incorruptible state. Sense as well as sentiment support film critic Robin Wood’s assessment that Reeves was “the controlling influence in the latter half of the film.” Wood was referring to the film’s wordless scenes played out in the Park of the Monsters of the Villa Orsini in Bomarzo. This Italian location, replete with grotesque oversized statuary, generates an atmospheric frisson that elevates the entire film; it’s the perfect backdrop when Drago’s loathsome henchman Sandro hacks an interloper to death with a large scythe – which he then uses the next day to mow the grass. The Park of the Monsters is also the setting for Sandro’s scary pursuit of the brave and resourceful Neep, a little person, whom Sandro finally corners and flings from the castle’s high battlement.

Cinematographer for The Castle of the Living Dead was no less a figure than Aldo Tonti, whose credits include classic films by Luchino Visconti (Ossessione), Roberto Rossellini (Il miracolo), Federico Fellini (Le notti di Cabiria), and John Huston (Reflections in a Golden Eye – although Huston’s frequent collaborator Oswald Morris actually shot most of that film). What puts Tonti’s photography for Castle on a level with those masters is the exterior footage in that monster-filled park, where the film – to again quote Wood – “ceases to be a standard horror movie and takes on the closely knit organization of poetry.” And if those scenes in fact belong to Warren Kiefer, the film’s credited writer/director, they appear to be the few noteworthy moments in an otherwise brief and unsung career.

Kiefer’s film has been absorbed into the movies and mythos of Michael Reeves, his nominal subordinate, just as the visual flair that occasionally illuminates director Robert Stevenson’s 1943 Jane Eyre is today enjoyed as a reflection of that film’s uncredited co-producer, who also starred as Rochester: Orson Welles. No surprise then to see the British DVD of The Castle of the Living Dead, released by Odeon in 2012 – almost fifty years after the film’s premiere – citing Reeves’ name four times on its back cover, while the front announces in a prominent blurb just above the film’s title, “Second unit director Michael Reeves.”

Also enlivening The Castle of the Living Dead for audiences today is the participation of Donald Sutherland, giving his first film performance. (So grateful was Sutherland for the gig that he named his son after director Kiefer.) Playing a dual role, Sutherland is terrific in both, mining comedy as an arrogant but inept police officer, while also arousing sympathy as an elderly and disfigured witch woman, whose (dubbed) voice speaks always in rhyme. Although frightening to others, she is in fact a benevolent character and seeks to help the troupe of actors lured by Drago to his castle so they can become his next victims. She rescues and revives Neep after he is hurled from the castle, and she ultimately takes down Drago, impaling him on his own formula-laden hook and paralyzing him in a grotesque posture of pain and terror.

Paul Maslansky, Castle’s executive producer, recalled Reeves directing the early parts of the film, which is also plausible, insofar as the opening includes Reeves’ onscreen appearance, hidden under a dark wig and moustache. He is the very first person you see, sliding his hand along a woman’s dress and leaning in for a kiss under the shade of a tree. He is immediately clubbed down from behind and falls onto his back, unconscious; an unknown hand then goes for his girlfriend’s face. Voiceover narration encourages the audience to regard this opening moment of violence as an aspect of life in a countryside filled with highwaymen and robbers, but the reality is they have been victimized by Sandro.

At the film’s climax, Count Drago displays the room where he keeps his collection of waxwork-like stiffs, and most prominent among the corpses is this same couple, now forever motionless, the woman seated in a chair with Reeves standing behind her.

Reeves also appears in an even briefer but far more significant bit part in his next film, The She Beast (called Revenge of the Blood Beast in England). With his first outing as a director, Reeves placed the witch front and center. This time she is a total monster: the hideous Vardella, fanged and scaly-skinned, who preys upon 18th-century villagers in Transylvania and then returns to wreak havoc two centuries later, on the anniversary of her gruesome execution. (In another instance of drag casting, she is played by stuntman Jay Riley.) The flashback to Vardella’s first death in 1765 is the film’s highlight, punctuated by handsome and eloquent long shots – a visual flourish Reeves would bring to high style in the location scenes of Witchfinder General. This sequence in The She Beast begins with glimpses of a young boy, his head bloodied as he runs in panic through the woods until he arrives at a church. Interrupting the funeral of a woman, he announces to the priest and the mourners that Vardella has killed his brother. With the priest’s encouragement, the enraged villagers pull torches off the walls and set out to kill the witch; but they ignore the protests of the church’s bellringer (also a little person, as wise as Castle’s Neep was), who warns that Vardella must first be exorcised by the vampire slayer Count Van Helsing, or else her curses will continue to plague the village. In a macabre touch, the little boy, left behind in the emptied church, walks up to the casket so he can gaze at the corpse.

When the furious mob descends on the cave where Vardella is hiding, she springs out at them in a startling attack, bloodying one man’s face with her claws. The crowd overpowers her and she is taken to a lake where a ducking stool is set up (a prop adapted by the canny Reeves from another film production’s catapult). But before they can execute her, Vardella declares, “On this day, be ye with your descendants cursed until eternity! Think not that ye are rid of me, for I Vardella will return! Vardella will return!”

Reeves intercuts close shots of village men – including himself in another cameo appearance – as Vardella curses them, after which, in a sadistic detail, she is nailed to the stool with a long red-hot spike, driven through her back until it protrudes from her chest, spilling her blood on the ground. The villagers then plunge the screaming witch again and again into the lake, with a joyful gusto more appropriate to a carnival than an execution.

This mayhem is vintage Reeves, and he would reinvent it in more realistic and appalling detail for Witchfinder General. Both films are reminders that the self-righteous harbor a horrific appetite for violence, a brutality that transforms ordinary people into monsters, even as they believe themselves to be heroes who are destroying monsters. Significantly, characters from this sequence in The She Beast recur in the film’s scenes set in present-day Transylvania. Count Van Helsing watches the awful execution silently from afar; his descendant will struggle to stop Vardella 200 years later. The villager who loudly rejected the bell ringer’s advice about exorcism – and who helps drive the spike into her body – is played by the same actor who appears in the 1965 scenes and is killed by the reanimated Vardella. Mel Welles – best remembered as the florist Gravis Mushnik in the original Little Shop of Horrors – gives an expert performance, both funny and repulsive, as the 20th-century hotel proprietor Ladislav Groper. He’s a drunkard and lecher, given to uttering the slogans of his country’s communist regime, although he supports nothing but his own vile habits and desires. From peeping on the lovemaking of newlywed guests to sexually assaulting his own niece, he is an utter reprobate, and Reeves uses him to define the hypocrisy and futility of the utopian ideals espoused by Transylvania’s latest regime. Calling the current Count Van Helsing “your ex-lordship,” Groper insists, “the government has outlawed black magic”; intruding on the newlyweds, he dismisses their protests, telling them, “no need to knock in the people’s republic” and “privacy breeds conspiracy.” What a joy it is when Vardella kills him with a sickle – which she then tosses aside so that it falls onto a hammer!

Groper is made to pay for the cruelty of his 18th-century ancestor as well as for his own depravity. By the same token, Reeves’ decision to include himself as one of the men cursed by Vardella is more than an in-joke; he was underscoring a despair that shaped both his films and his life. A few years after making The She Beast, he would be crushed by the burden of his own lineage, killed by the excessive and conflicting medications that doctors fed him to treat his bouts of depression – a condition that afflicted his father and his father’s father.

Reeves’ conviction that the past cannot be escaped is driven home by the fate of The She Beast’s newlyweds. The husband Philip is played by Ian Ogilvy, who first became friends with Reeves when they were both 15 years old, and who would go on to star in The Sorcerers and Witchfinder General. An excellent actor, charismatic and believable, he would make a name for himself playing Simon Templar, the heroic criminal known as The Saint, in the 1970s British television series. But unlike his subsequent performances for Reeves, Ogilvy is underutilized in The She Beast, cast in the one-note role of a desperate husband separated from his bride, who has disappeared and been replaced by Vardella. As his wife Veronica, Barbara Steele is alas even more underused. Available to the production for only a brief time, her performance bookends the film, but she brings to all her scenes the full effect of her lovely yet peculiarly unsettling presence. When they drive away from Groper’s hotel, Philip is unable to control the car as they pass the lake where Vardella was killed, and it veers straight into the water. He emerges from the engulfed car, but the only woman pulled out of the lake is the unconscious Vardella, not Veronica. Once the witch is revived the killings commence, her spree ending only when she is sedated by Count Van Helsing’s descendant, returned to the ducking stool, and plunged back into the lake. Vardella disappears in its waters, and the revived Veronica floats to the surface. But at the film’s end, after they have fled Transylvania and arrived in Czechoslovakia, Veronica announces with a thin smile, “I’ll be back” – making plain that she is possessed by Vardella, whose vengeance is unstoppable.

Possession is also the dominant theme of The Sorcerers, but here the titular witchery is metaphoric, represented by the old woman Estelle Monserrat, whose husband Marcus has devised hypnotic machinery that enables the couple to dominate another person’s mind and feel whatever their subject feels. As Estelle, Catherine Lacey delivers the stand-out performance of her long career, which includes working with Alfred Hitchcock (The Lady Vanishes, her first film), Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger (I Know Where I’m Going!), and Alexander Mackendrick (Whiskey Galore!). She is a perfect match for the great Boris Karloff as Marcus, and the conflict between the two becomes the engine of the film’s drama, rather than their victim’s internal struggle.

Marcus’ dream is to use his scientific breakthrough to bring new life and sensations to people shut away in hospitals and nursing homes, but Estelle redirects their psychic control to obtain stolen goods and live out forbidden thrills, losing her mind and compelling their thrall to commit murder. The Monserrats’ battle escalates in viciousness, and she boasts to her husband, “My will is stronger than yours.” In a mad fit Estelle destroys his laboratory, using his own cane to smash his machinery so there can be no deprogramming. Only when her mind is clouded by alcohol can Marcus assert sufficient control to have their proxy crash his car and die in flames – which immolates the Monserrats as well, their bodies charred black while their clothing remains undamaged.

As the man whose mind is enslaved in The Sorcerers, Ian Ogilvy always maintains a realistic naturalness, even when his actions are not his own. It’s an expert performance, drawing out the audience’s compassion in his moments of lucidity, when he is overcome by confusion, guilt, and terror at his inexplicable behavior. By nature a volatile and spontaneous character, he is the perfect subject for the Monserrats, and Marcus encounters no resistance when he in effect picks up the bored young loner who has just walked away from a date with his girlfriend.

Marcus offers him “Dazzling, indescribable experiences – complete abandonment with no thought of remorse,” while Estelle promises, “intoxication with no hangover, ecstasy with no consequences.” The ultimate voyeurs, the Monserrats are of course offering exactly what they will derive by controlling him. They’re also describing the allure of the movies – sitting in the dark and experiencing vicarious, guilt-free thrills of sex, violence, crime, murder. Along with this implicit criticism of its own medium, The Sorcerers is also a prescient takedown of 21st-century virtual reality, the latest wrinkle in our long history of inventing artificial forms of existence. For the 1960s the film was also a slap at the drug generation, and Reeves made sure to depict the operation of Marcus’ hypnotic machinery in a psychedelic scene evocative of an acid trip.

All of these avenues of unreality, however, lead only to one place, the inner core of the individual, which in Reeves’ films is a hidden cauldron of desire and violence. When Estelle persuades Marcus to let their subject steal a fur coat for her, she tells him what it means “to be human,” saying, “We all want to do things, deep down inside ourselves, things we can’t allow ourselves to do. But now we have the means to do these things without the fear of consequences.” And Marcus, despite his noble aspirations, has to admit to her about their long-distance experience of suspenseful thievery, “I did enjoy it.”

Reeves developed The Sorcerers‘ battle of wills between wife and husband at Karloff’s urging, so repelled was the veteran actor by the original script, then entitled Terror for Kicks, in which both Monserrats were predators. Finding the characterization immoral and unacceptable, he insisted that his role be made more sympathetic, and Karloff’s instincts provided a great boost for the film, animating its narrative with the growing conflict between Marcus and Estelle, which in turn made the plight of their psychic victim all the more uncertain and harrowing.

These script revisions also brought out autobiographical overtones for Michael Reeves – an important subtext in The Sorcerers, considering that the Monserrats are controlling a young man named Mike Roscoe. It’s no accident that, even before he loses his autonomy, Mike is chided by a friend for his “bloody artistic temperament.” The film’s reverberations of Reeves’ own parents are deepened by the spectacle of Marcus being eclipsed by Estelle’s greater power. Reeves’ father died suddenly in 1952, only a few days before the eight-year-old Mike, an only child, was sent to a boarding school far from his Essex home; his paternal grandfather also died later that same year, just two days before Mike’s ninth birthday. The boy’s consolations were the movies, with which he was already besotted (his father had given him 8- and 16-mm cameras), and his mother, who became the dominant presence in his life. The full extent of Betty Reeves’ possessiveness, however, was revealed only after her adult son had been rendered impotent by the drugs his doctors were prescribing. One of those doctors, in a shameful breach of professional ethics, introduced Reeves to another of his patients – Ingrid Cranfield, then suffering from anorexia – in the hope that an affair would develop between them and revive Reeves’ libido. As Cranfield recounts in her moving 2007 memoir At Last Michael Reeves, this doctor “gave me instructions. ‘Suck it,’ he said, ‘if you can bear it.’” He also told her that “Michael’s mother, now in her sixties, had tried to cure him of his impotence by getting into bed with him and coaxing him. She was a woman, after all.”

Witches are the explicit focus of Reeves’ final film, Witchfinder General, only this time there are no actual witches, only women (and men) who are falsely accused. The monsters in this film are the profiteers and the self-righteous – the sadists Reeves had taken a swipe at with the cruel 18th-century villagers of The She Beast. From its opening image, a far shot of a gallows being erected in an idyllic countryside, Witchfinder General depicts mid-17th-century England as a world of natural beauty, blighted by the barbarisms of people. The opening scene depicts the hanging of an accused witch, the tormented woman screaming and screaming and screaming as she is led to her death, a priest reciting an especially lurid passage from The Book of Revelation, the angel who announces, “Come! Be gathered together to the great supper of God, that you may eat the flesh of kings, the flesh of captains, the flesh of mighty men, and the flesh of horses and of those who sit on them, and the flesh of all men, both free and slave, small and great.” These lines have special relevance: King Charles I will soon be toppled and executed by the forces of Oliver Cromwell, and Captain Richard Marshall will battle to the death with mighty man Matthew Hopkins, the witchfinder (introduced sitting on his horse, watching this execution from a distance), at the cost of both their souls.

Ian Ogilvy stars as Marshall, a soldier in Cromwell’s army, seen battling royalists in a brutal gunfight amid the country’s lush forests. Richard visits his beloved Sara and leaves her in the care of her uncle, the town priest, so he can return to England’s civil war; on the road from town he encounters a group of villagers awaiting the arrival of Matthew Hopkins. Once among them, Hopkins has Sara’s uncle arrested, tortured, and imprisoned for witchcraft. He spares the priest further abuse only after Sara submits to his sexual advances. But when Hopkins returns the next evening to force himself on Sara again, this time he is observed by his despicable assistant Stearne. Reeves’ recurring theme of voyeurism accelerates the plot, with Stearne then overpowering and raping Sara as well – after which Hopkins rejects her and condemns her uncle to death. When Richard returns to his traumatized fiancée, he brings her into the church, now desecrated and vandalized by the irate villagers, and conducts their own marriage ceremony; he also holds up his sword and pledges to take revenge on Hopkins. That moment in their wedding is Richard’s only real bond: When Sara embraces him before he leaves to rejoin the army, he automatically pulls away from the touch of his despoiled wife, in his own way as repelled by her as Hopkins was.

Although promoted by Cromwell himself from cornet to captain, Richard shuns this duty as well, and he deserts his responsibilities to pursue Hopkins and Stearne. When his comrade in arms Trooper Swallow protests, “It’s madness,” Richard offers no denial, replying only, “It’s justice. My justice.” He tracks the witch hunter to a village where Hopkins is busy dispensing his own justice, having an accused witch tied to a ladder and then dropped into a flaming pyre. In a classic instance of the misogyny that characterizes rapists, Hopkins refers to this atrocity as “a fitting end for the foul ungodliness in womankind” and muses, “Strange isn’t it how much iniquity the Lord vested in the female.”

Reeves makes sure to depict numerous children in the crowd that witnesses this execution. He also shows some of the youngsters roasting potatoes in the remnants of the fire, an image that recalls the little boy who ran to the church in The She Beast: Urged to tell where they can find his brother’s killer, he first demands, “If I tell you, will you kill her?” Only after he is assured they will, does he reply, “She’s in the cave above the lake.”

When Hopkins discovers that Sara is also in this town where he is killing witches, he has her arrested so he can draw the vengeful Richard into a trap. Once he has captured them both, Hopkins has Sara tortured before the chained-up Richard – whose only reaction is to quietly tell Hopkins, “I’m going to kill you.” Stearne is instructed by Hopkins to bring Richard closer to Sara’s torment, but Richard overpowers Stearne, kicking him in the head with such viciousness that he loses an eye. The swiftness of this sudden violence is made more horrifying when Richard grabs an ax off the torture chamber’s wall and slams it into Hopkins’ body.

Swallow and the other soldiers, arriving to rescue Richard and Sara, come upon this scene of stunning brutality, Richard chopping into Hopkins again and again. Witnessing the insanity he had warned against, Swallow ends Hopkins’ agony by shooting him. But the gunshot does not free Richard from his madness – he can only turn on his friend and snarl, “You took him from me!” over and over. The film ends with Sara also caught in an unending loop of horror, and like the accused witch victimized by Hopkins in the film’s opening scene, she can only scream and scream and scream.

Scream and Scream Again was the horror film Reeves would have directed in 1970, had he lived, and it would have reteamed him with Vincent Price – an unexpected collaboration, insofar as the two men fought constantly in making Witchfinder General. Reeves, disappointed at not having Donald Pleasence play Hopkins, was determined not to indulge Price in the humor and flamboyance that the actor had brought to his other horror films. They clashed throughout production, and stories abound of Reeves’ insulting treatment of Price, and of Price’s fury at Reeves. Ogilvy recalled the director telling his star, “Could you take it DOWN a bit?” and “I really don’t want one of these Edgar Allan Poe performances. I actually want a real man.” That last remark was a double-edged shiv, with Price being bisexual and prone to camp off- and onscreen. (Price would say of Ogilvy, “Oh my God! She’s so pretty and she rides that fucking horse so well!”) To the film’s composer Paul Ferris, Price declared, “That young Michael Reeves, he’s so young, so handsome, so talented, and I hate him!” Summing up the tensions is a photograph of the two men on location, each turning away from the other as if repulsed by his very sight.

Yet despite it all, Price was willing to join Reeves again, realizing just how powerful a performance he had given in Witchfinder General. In April of 1968 he wrote to “my dear Michael,” admitting, “in spite of the fact that we didn’t get along too well – mostly my fault as I was physically and mentally indisposed at that particular moment in my life (public and private) – I do think you have made a very fine picture and what’s more I liked what you gave me to do!” But the various projects that were proposed for Reeves along with Scream and Scream Again – the Poe story The Oblong Box, biopics De Sade and Bloody Mama, the incest drama The Buttercup Chain, an adaptation of the Walker Hamilton novel All the Little Animals (which Reeves was especially keen to film) – all would pass into other hands after his death in February of 1969.

Although some have called Michael Reeves a cult figure, such a description is lazy and misleading – no one refers to Jean Vigo or James Dean as cult figures. Condescension to the horror genre has prompted such an underestimation. The truth is, Reeves was a born filmmaker, whose life ended far too early. Possessed by the specter of the witch, in his art and his life, he also possessed his own extraordinary gifts and a unique personal vision. His legacy has changed not just how we see films but how we see ourselves as well, forcing us to confront the hatred and cruelty that underlie our passion for condemning the lives of others.

(This essay, written in 2022, appears here for the first time.)

SOURCES

“the controlling influence”

“ceases to be a standard horror movie”

Robin Wood, “In Memoriam Michael Reeves,” in Movie, Winter 1969–70, p. 2.

“gave me instructions”

“Michael’s mother, now in her sixties”

Ingrid Cranfield, At Last Michael Reeves: An Investigative Memoir of the Acclaimed Filmmaker. Lulu, 2007, p. 16.

“Could you take it DOWN a bit?”

Benjamin Halligan, Michael Reeves. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003, p. 136.

“I really don’t want”

John B. Murray, The Remarkable Michael Reeves, His Short and Tragic Life. Baltimore: Luminary Press, 2004, p. 147.

“Oh my God!”

“That young Michael Reeves”

Murray, The Remarkable Michael Reeves, p. 152.

“my dear Michael”

“in spite of the fact”

Murray, The Remarkable Michael Reeves, p. 206.

Link to:

Film: Essays: Contents

For more on Michael Reeves, see:

Film Dreams: Michael Reeves