Where Is The Other Side of the Wind?

or

¿Quien Es Mas Macho: Orson Welles, John Huston, o Ernest Hemingway?

When Orson Welles died on October 10, 1985, at the age of 70, he left behind a cluttered legacy that rivaled Charles Foster Kane’s wilderness of statuary at the end of Citizen Kane. He’d been working on numerous films in his last years, mostly adaptations, which now exist as fragments: Don Quixote, The Merchant of Venice, The Deep, Moby-Dick, The Dreamers. But the inventory also includes an original project called The Other Side of the Wind, which Welles began shooting in the summer of 1970 and had essentially completed before his death. Yet this film too has become the stuff of legend, unseen and unavailable for decades, despite the dedicated efforts of his collaborators to retrieve it from oblivion.

A scathing satire of Hollywood, The Other Side of the Wind also sends up Hemingwayesque machismo, and the film originates with Welles’s own relationship with Hemingway. Writer Peter Viertel, in his memoir Dangerous Friends, recalled a 1958 encounter with Welles in Biarritz, when their conversation turned to the bullfighter Antonio Ordóñez – and to “Papa” Hemingway:

Welles was a fervent Ordoñista […] His relationship with Hemingway was less than cordial, and I joked with him about the love and admiration he shared with Papa for the young matador from Ronda.

He confided in me that he was writing a screenplay about an old man’s obsessive admiration for a young torero; the protagonist of his story was an aging movie director intent on recapturing the magic of his youth by following a young bullfighter around Spain. […]

“Are you writing about yourself or Papa?” I asked him.

“About both of us,” he bellowed before succumbing once again to uproarious laughter.

This version of The Other Side of the Wind, then entitled The Sacred Beasts, lost its bullfighting angle in the 1960s, when Welles saw the corrida as having become too touristy and phony. The character of his protagonist, however, was brought into focus through his collaboration with the Yugoslavian writer Oja Kodar. Most familiar from her appearance in Welles’s F for Fake, which she also co-scripted, Kodar first met Welles in Zagreb in 1961, when he was preparing The Trial, and became not just his collaborator but his companion as well – that is, whenever he was away from his wife, Paola Mori (who’d played Arkadin’s daughter in Welles’s Mr. Arkadin). Kodar told Jonathan Rosenbaum that she gave the director character his itch for seducing the girlfriend of his leading man: “[He] gets a real kick from the idea of sleeping with his leading man […] he is not a classic homosexual, but somewhere in his mind he is possessing that man by possessing his woman. And at the same time, just because there is hidden homosexuality in him, he is very rough on open homosexuals, as so many of those guys are.”

This slant fit right into Welles’s experience of Ernest Hemingway, who’d personally instructed him in unnecessary roughness and homophobia. The two first met in the spring of 1937, when the 22-year-old Welles was asked to read Hemingway’s narration for The Spanish Earth, Joris Ivens’ documentary on the Spanish Civil War. Years later, Welles described their encounter for Cahiers du cinéma and turned it into a baroque Wellesian film sequence, complete with bullfighting metaphor. Telling his interviewers that he’d found some of Hemingway’s lines “pompous and complicated,” Welles said he’d recommended some cuts:

This didn’t please him at all, and since I had, a short time before, just directed the Mercury Theatre, which was a sort of avant-garde theatre, he thought I was some kind of faggot and said, “You – effeminate boys of the theatre, what do you know about real war?”

Taking the bull by the horns, I began to make effeminate gestures and I said to him, “Mister Hemingway, how strong you are and how big you are!” That enraged him and he picked up a chair; I picked up another, and right there, in front of the images of the Spanish Civil War as they marched across the screen, we had a terrible scuffle. It was something marvelous: Two guys like us in front of those images representing people in the act of struggling and dying.

As for Hemingway’s take on Welles, Viertel’s Dangerous Friends describes a genteel social gathering one afternoon in 1948, when John Huston asked Papa why Welles didn’t narrate The Spanish Earth. Hemingway answered, “Every time Orson said the word ‘infantry,’ it was like a cocksucker swallowing.”

Whatever actually happened between Welles and Hemingway, it’s clear that some serious buttons concerning sexuality and masculinity had been thumbed. In The Other Side of the Wind, Welles pried out those buttons with his depiction of director Jake Hannaford, the macho survivor of a bygone Hollywood, who’s now scrambling for end money to complete an artsy sex-&-violence extravaganza that he hopes will salvage his flagging career. Ultimately, he’s forced to confront his own repressed sexual desire for his film’s handsome young leading man, and the knowledge drives him to take his own life.

“This director who isn’t me” is how Welles described him to the American Film Institute, joking at the obvious parallels between Hannaford’s estrangement from Hollywood and his own tangential career. Of course, as he’d admitted years earlier to Viertel, a good deal of autobiography had gone into the character along with a good deal of Hemingway. But Hannaford also became a full-blown entity for Welles: “If I were a 19th-century novelist, I’d have written a three-volume novel. I know everything that happened to that man. And his family – where he comes from – everything; more than I could ever put in a movie. His family – how they were competing with the Kennedys and the Kellys to get out of the lace-curtain-Irish department. I love this man and I hate him.”

Hannaford’s name reflects a variety of inspirations, starting with Welles himself: “Jake” was a long-standing nickname he’d received from no less of a man’s man than Frank Sinatra. Hannaford has aural similarities to the name Hemingway, of course; even more plainly, it alludes to John Ford, the legendary director who’d been the patriarch of Hollywood’s Irish Mafia – what Welles called “all those hairy good companions of Ford’s famous clan,” he-men such as John Wayne and Ward Bond. Jake Hannaford also points to John Huston, and not just because they share initials. Huston’s name came up even as Welles was telling his biographer Barbara Leaming that Hannaford was based on another Irishman, the silent-film director Rex Ingram: “He was considered a great filmmaker at one time – and he wasn’t. He made terrible movies. They’re awful! He was a great fascinator like John, in the high style of a great adventurer, a super-Satanic intelligence, and so on. He was a great director as a figure, in the way that John is. That’s why John is so perfect for it.”

John Huston – boxer, big-game hunter, gambler, drinker, womanizer – spent his life perfecting the role of the Hemingwayesque macho; the role of Irishman too, having become an official Irish citizen in 1964. He was also far chummier with Hemingway than Welles ever became (although Viertel suggests that Papa never stopped being amused by the thought of former-boxer Huston as a “light heavyweight”). The two directors had been friends since the mid 1940s, when Huston scripted Welles’s The Stranger; he subsequently directed Welles in Moby Dick, The Roots of Heaven, and The Kremlin Letter. In looking to Huston for his Jake Hannaford, Welles was also trading on stories about Huston when he was broke and stranded in London during the early 1930s. Of Huston’s many biographers, only Axel Madsen mentions him “rolling drunks and homosexuals in Hyde Park.” His source is apparently Peter Viertel: traumatized after having worked with Huston on the scripts of We Were Strangers and The African Queen, Viertel wrote a nasty novel about their collaboration called White Hunter, Black Heart, in which “John Wilson” tells “Peter Verrill” of “the early years of his life, which he had spent in London. He had been terribly poor and out of a job, and had taken to rolling drunks and fairies in Hyde Park. I had heard the stories before, but they sounded much better told in their actual locale.” More evidence can be found in another roman à clef, Charles Hamblett’s The Crazy Kill, a novelization of the author’s time on location with Huston during the shooting of Moby Dick. Although Hamblett regarded his subject far more worshipfully than did Viertel, he also recalled the same dirty little story, again as a familiar anecdote. Here however it’s offered in tribute, as part of a catalog of the down-to-earth types who can testify to the wonderfulness of “John Simpson”: “And someone will tell you how he shook down a couple of lilies and placed the proceeds on an eight-to-one winner at Longchamps and lost it all to some dame he had been shacked up with.”

No such anecdotes are to be found in Huston’s autobiography An Open Book, of course. But there is a chapter devoted to The Other Side of the Wind, in which Huston called Hannaford “a director […] who comes to the end of his rope. Orson denied that it was autobiographical in any way, nor was it biographical as far as I was concerned.” In terms of the particulars about Hannaford, that statement of course is true. Equally true – whether it actually happened or not – is the exchange between Welles and Huston which Lawrence Grobel reports in his bio The Hustons: Huston asked, “What is The Other Side of the Wind?” and Welles replied, “It’s a film about a bastard director who’s full of himself, who catches people and creates and then destroys them. It’s about us, John. It’s a film about us.”

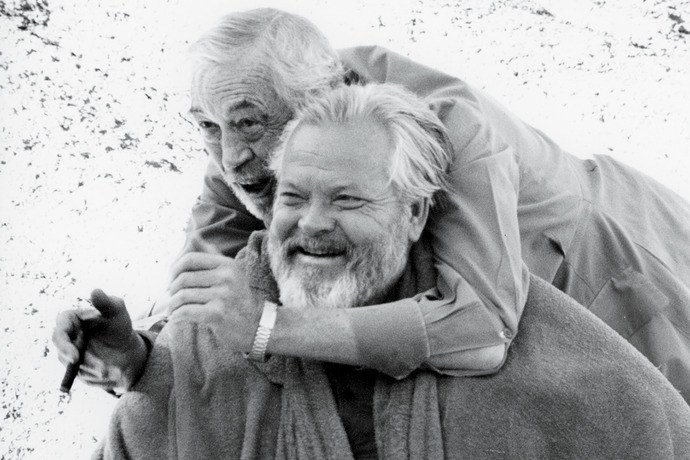

The Other Side of the Wind was so much about them both that Welles struggled for years over which of them should play the lead. He may have first approached Huston as early as 1969, during the shooting of The Kremlin Letter: Early in 1974, while on the set of The Other Side of the Wind, Huston told After Dark magazine, “Several years ago, Orson told me he had an idea for a film and he’d said he’d like to have me do it. I automatically said yes. But I didn’t get the script he said he would send me. Some time passed and I heard he was making the film. I assumed he had given someone else the role we’d talked of earlier. But not at all.” Welles had begun shooting with the part still uncast, planning to cut Hannaford into the rest of the footage once he’d made up his mind who would play him. Peter Bogdanovich recalled “Orson in Paris pacing up and down the street at night, arguing with himself as to who should play the old director, he or Huston – wanting to keep the plum role for himself: ‘Why should I give that great part away!?’ – but feeling that Huston was better for it.” Once he gave Huston the nod, though, Welles seems never to have regretted it. In 1976 he told The New York Times, “John Huston gives one of the best performances I’ve ever seen on the screen. When I get to the Heavenly Gates, if I’m allowed in, it will be because I cast the best part I ever could have played myself with John Huston. He’s better than I would have been – and I would have been great!”

Huston was equally impressed by Welles. “I had enormous regard for Orson,” he told Grobel. “More than any other director I have ever seen, he arranged the words, wrote the scenes overnight, did the lighting and the set decorations, took a camera and shot the scene himself – it was awesome.” Huston summed it up to After Dark: “Orson was just at his best – which is a hell of a big thing to say.” He’d also reported his enthusiasm to Viertel, whose Dangerous Friends turns The Other Side of the Wind into a Huston film, not unlike the way Welles had turned his own introduction to Hemingway into a Welles film:

Orson had always scoffed a little at Huston’s personage, probably because he recognized a rival act when he saw one, but before they had finished the first week of working together he fell under the spell of John’s charm and larger-than-life personality, feelings that were mutual. John told me that he had enjoyed the experience […] because the movie was “such a desperate venture.” Halfway through many of the scenes a bailiff would arrive to confiscate Orson’s camera or the lighting equipment, which made the work the kind of perilous undertaking John enjoyed, an adventure shared by desperate men that finally came to nothing.

“Nothing,” fortunately, is way off the mark. This story has a happier ending than The Treasure of the Sierra Madre or The Man Who Would Be King. But after Welles’s death, The Other Side of the Wind almost did become more of a John Huston film. Late in 1986 Kodar and Bogdanovich approached the 80-year-old director to help complete the film, even though he was already committed to begin another project. Seeing Huston confined to a wheelchair and hooked up to an oxygen tank didn’t inspire confidence in Kodar that he could also take on The Other Side of the Wind – and in fact by then he had less than a year to live; his sublime James Joyce adaptation The Dead would be his last film. Huston suggested that his son Danny could take over for him if he wasn’t up to it, but the idea seemed foolish to Kodar: Why entrust Welles’s vision to someone who wasn’t around for any of the shooting? This particular adventure did finally come to nothing, once Danny leaked the story of his father’s consultation with Bogdanovich. The New York Daily News reported it – “It looks as if Orson Welles’s unfinished The Other Side of the Wind will finally be finished – by John Huston” – and the already fragile negotiations to retrieve Welles’s film were further complicated, with the middlemen singing a tune along the lines of, ‘If you’ve got Huston on board, then surely you can pay a little more for it…’

Dominique Antoine, Wind’s French co-producer, told Jonathan Rosenbaum that, by then, “the film was very nearly completed,” because Welles had already assembled “a rough cut with the aid of no less than eleven movieolas, arranged in a semi-circle.” The catch was and continues to be who actually owns the footage. The hideous story of the film’s legal entanglements and rights confusions is an international nightmare worthy of Gregory Arkadin, filled with thieving Spaniards, duplicitous Iranians, and litigious Frenchmen. (Leaming’s bio Orson Welles spells it out in gruesome detail.) With Welles’s death – and the death of his widow, Paola Mori, in an auto accident a year later – the task of extricating this film from its legal limbo became even more difficult. Kodar and Bogdanovich didn’t announce any real progress until 1991, when Variety reported on their efforts with the help of Frank Marshall.

Executive producer for Steven Spielberg and the director of Arachnophobia and Alive, Marshall had been line producer on The Other Side of the Wind from 1972 to ’77, a job that required him to do, as he told this writer, “everything!” from assembling the crew to cooking their meals. Welles also wouldn’t hesitate to telephone Marshall at 5 A.M. and instruct him to gather everyone to his Arizona location simply because the light was beautiful on that particular day. “Working with Orson was a 24-hour job,” he recalled. “His creativity knew no bounds.”

Back in 1991 Marshall told Variety that the shooting of The Other Side of the Wind had been completed – “It’s just a matter of getting the stuff assembled. It would be nice for the history of movies to get this thing done at last. We’ve talked to a couple of studios. It always comes to the crux of, ‘If you’ve got the rights, come talk to us.’” Early in 1999, Marshall told Film Journal International, “Peter Bogdanovich and I are very close to putting together the financing to finish that movie.” In the fall of 2002, he told this writer that out of everyone who has considered the film, the cable network Showtime was “the only serious company to take a look at it.” Showtime’s lawyers have taken on the task of hammering out the film’s ownership problems, after which the final assembly of the film can commence. Nevertheless, as of this writing, the rest is still silence…

If you want to see footage from The Other Side of the Wind, all that’s currently available are a pair of excerpts shown as part of the AFI’s Life Achievement Award ceremony for Welles, which was televised in 1975 and is available on videocassette. Hosted by Frank Sinatra, it’s the standard parade of film clips and testimonials, but towards the end Ol’ Blue Eyes announces, “You know, so far tonight we’ve talked a great deal about Orson’s many achievements in the past. Now how about a look at the future of our gifted friend?” In Touch of Evil, when Welles asks Marlene Dietrich to read her Tarot cards and tell him his future, she replies, “You haven’t got any. Your future’s all used up.” That film, made in 1958, was the last time Hollywood hired him as a director. Seventeen years later, still struggling to turn the situation around, Welles screened two clips from his current project.

The first features Jake Hannaford’s birthday party: a media circus where the great man is hounded by the cameras, lights, and microphones of a horde of reporters, documentarians, and other cinemaniacs. “The joke is that the media are feeding off him, but they end up feeding off themselves,” Welles told film critic Joseph McBride – who’d approached him for an interview and was immediately enlisted to play an annoying critic who pesters Hannaford. Huston is in his element as the lionized auteur, hiding his displeasure at the omnipresent media with a false, grinning heartiness. The scene includes glimpses of Peter Bogdanovich as a young director whose megasuccessful career has eclipsed that of his idol, and Susan Strasberg, playing a shrewish film critic who tries to challenge the boy’s club of directors.

“Glimpsed” is indeed the operative verb here, because Welles continuously fragments the flow of visual information. He intercuts footage from all those cameras wielded by the media, juxtaposing a multitude of different angles, lighting, and textures, and even throws in some still photos. His frenetic editing style suggests a cinematic equivalent of cubism, only with time being overlapped as well as space, insofar as the cutting includes repetitions of action caught by the different cameras of the spectators. This radical approach to shooting and editing negated traditional continuity concerns, and so Welles didn’t shrink from shooting Hannaford scenes without a Hannaford; he was also free to revise casting during production, as his conception of the characters changed – or as his actors became unavailable. When McBride’s scenes were shot, Peter Bogdanovich was playing a hack writer who was trailing Hannaford to compile an interview book with the great man – a parody of his own relationship with Welles, as the two were then in the thick of the conversations that would eventually become This Is Orson Welles. The role of the superstar younger director was then being played by the comedian and impressionist Rich Little – whom Frank Marshall recalls walking off the set of The Other Side of the Wind simply because “he had to go”: Little’s other commitments had finally made it impossible for him to continue acting for Welles. Once Bogdanovich took over the role, Welles’s parody cut much closer to the bone, as Bogdanovich was then riding high on the box-office success of The Last Picture Show, What’s Up, Doc?, and Paper Moon.

Frankly, it was bizarre of Welles to think that his ticket back into Hollywood would be an avant-garde parody of the industry. But at the AFI celebration, he still believed he had a shot at getting help from The Players in finishing his film. In his acceptance speech, rather than launch into the James Mason routine from A Star Is Born and start pleading, “I want a job,” Welles screened a second clip from The Other Side of the Wind. In it, his longtime colleague Norman Foster (who co-directed and signed Journey into Fear) plays a Hannaford stooge who screens excerpts from Jake’s unfinished feature for an underwhelmed studio exec.

Welles’s slice-and-dice editing also characterizes this scene, even though no spectator cameras are present for the frosty viewing-room meeting. Only the clips from Hannaford’s film introduce a different visual feel, one far more familiar and coherent. Unfortunately, Hannaford’s story is neither familiar nor coherent; with its insertions of “scene missing” titles and its arbitrary, symbolic action, the footage is more confusing than Welles’s prismatic editing of the real-life scenes. Hannaford’s movie emphasizes the glossy, reflective surfaces of high-rises, department stores, and office buildings, and suggests no one so much as Michelangelo Antonioni – a director whom Welles disliked almost as much as Rex Ingram. His point is that the emperor has no clothes, that Hannaford is making a lousy movie; but the shots of the cute male lead tailing the icy beauty Oja Kodar actually look good. They’re good looking, however, in a way that Welles disdained and would never have resorted to for himself. They also fail to impress the studio head, who realizes that Hannaford is making it up as he goes along.

This scene is just one more score that Welles was settling with The Other Side of the Wind: Mr. Big, a former actor turned mogul, is plainly based on Robert Evans, who had turned up his nose at distributing F for Fake when he was head of Paramount. Charles Higgam, a pompous critic played by Howard Grossman, is Welles’s lampoon of author Charles Higham, whose book The Films of Orson Welles gave new life to the tales of Welles’s neurotic inability to complete his films. Susan Strasberg’s role of Juliette Rich is a takeoff on Pauline Kael, who had earned Welles’s ire with her vicious essay on Citizen Kane, in which she accused him of trying to steal credit for a screenplay that she alleged was solely the work of Herman J. Mankiewicz. (Her exercise in pseudo-scholarship has long been thoroughly debunked.) Welles may even have been settling a score with “rival act” John Huston by having his old friend live out on film the catastrophe of repression. And in depicting the collapse of Jake Hannaford, Welles was also most definitely closing the books on Ernest Hemingway: The date of Hannaford’s birthday party is July 2, the anniversary of Hemingway’s suicide.

Welles originally conceived Jake Hannaford, “this director who isn’t me,” as an old man devoted to a young Spanish bullfighter in an attempt to recapture his own youth and innocence: another Charles Foster Kane, dying as he calls for the lost toy of his childhood. On May 6, 1988, Welles’s 72nd birthday, his ashes were buried in a dry well on the ranch of the bullfighter Antonio Ordóñez in Ronda, Spain. When Orson was 18 years old, he’d spent the summer there, learning how to fight in the corrida.

(This essay first appeared in Cineaste, Winter 2003.)

SOURCES

“Welles was a fervent Ordoñista”

Peter Viertel, Dangerous Friends. New York: Doubleday, 1992, page 356.

“[He] gets a real kick”

Jonathan Rosenbaum, “The Invisible Orson Welles,” Sight & Sound, Summer 1986, page 168.

“pompous and complicated”

“This didn’t please him at all”

Juan Cobos, Miguel Rubio, & J.A. Pruneda, “A Trip to Quixoteland: Conversations with Orson Welles,” Cahiers du cinéma, No. 5, 1966, reprinted in Interviews with Film Directors, Andrew Sarris, ed. New York: Avon Books, 1967, pp. 546-47.

“Every time Orson said the word ‘infantry’”

Viertel, page 46.

“This director who isn’t me”

AFI Life Achievement Award to Orson Welles, February 1975.

“If I were a 19th-century novelist”

Orson Welles & Peter Bogdanovich, This Is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins, 1992, page 171; emphasis Bogdanovich’s.

“all those hairy good companions”

Welles & Bogdanovich, page 27.

“He was considered a great filmmaker”

Barbara Leaming, Orson Welles. New York: Viking Press, 1985, page 472; emphases Leaming’s.

“light heavyweight”

Viertel, page 47.

“rolling drunks and homosexuals in Hyde Park”

Axel Madsen, John Huston. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1978, page 34.

“the early years of his life”

Peter Viertel, White Hunter, Black Heart. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1953, page 26.

“And someone will tell you how he shook down”

Charles Hamblett, The Crazy Kill. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1956, page 15.

“a director […] who comes to the end of his rope”

John Huston, An Open Book. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980, page 342.

“What is The Other Side Of The Wind?”

“It’s a film about a bastard director”

Lawrence Grobel, The Hustons. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1989, pp. 676-77.

“Several years ago, Orson told me he had an idea”

Viola Hegyi Swisher, “Orson Welles and Five Years of The Other Side of the Wind,” After Dark, March 1976, page 66.

“Orson in Paris pacing up and down the street”

Welles & Bogdanovich, page xxii.

“John Huston gives one of the best performances”

Charles Higham, “The Film That Orson Welles Has Been Finishing for Six Years,” The New York Times, 03/19/76, page 15.

“I had enormous regard for Orson”

Grobel, page 676.

“Orson was just at his best”

Swisher, page 66.

“Orson had always scoffed a little”

Viertel, Dangerous Friends, pp. 389-90.

“It looks as if Orson Welles’s”

Marilyn Beck, “Coast To Coast,” The New York Daily News, 12/06/86, page 6.

“the film was very nearly completed”

“a rough cut with the aid of”

Rosenbaum, page 168.

“everything”

“Working with Orson was a 24-hour job”

Frank Marshall, interview with the author, 09/17/02.

“It’s all shot”

uncredited, “All’s Welles That Ends …,” Variety, 10/01/91, page 2.

“Peter Bogdanovich and I are very close”

Ed Kelleher, “Glory Days,” Film Journal International, February 1999, page 45.

“the only serious company to take a look at it”

Marshall, interview with the author, 09/17/02.

“You know, so far tonight we’ve talked a great deal”

AFI Life Achievement Award to Orson Welles, February 1975.

“The joke is that the media are feeding off him”

Joseph McBride, Orson Welles. New York: Da Capo Press, 1996, page 194.

“he had to go”

Marshall, interview with the author, 09/17/02.

Link to:

Film: Essays: Contents

For more on The Other Side of the Wind, see:

Film Dreams: Orson Welles

Film Essay: Orson Welles and the Other Side of Nicholas Ray

For more on John Huston, see:

Film Dreams: John Huston

Film Interview: Danny Huston

Film Review: The Dead

Film Review: Under the Volcano