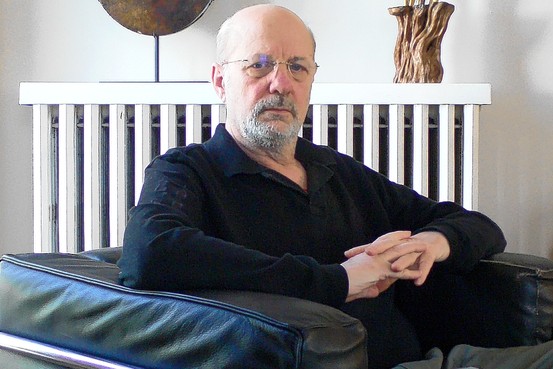

Interview with Rudolph Wurlitzer

Q: I’d like to start with your family business – because it really is one.

WURLITZER: Yeah, it was until me.

Q: Was Rudolph Henry Wurlitzer your father?

WURLITZER: My grandfather.

Q: The first Rudolph Henry Wurlitzer was born in 1831. That’s your great-grandfather?

WURLITZER: My great-grandfather, yeah. I didn’t realize it was ‘31. I thought it was later.

Q: He left Saxony and came to the States in 1853, and founded the Rudolph Wurlitzer Company in 1872.

WURLITZER: Yeah, that’s my great-grandfather. My grandfather continued it, and then my father was a part of it. He was really a Bernard Berenson-kind of scholar and was interested in stringed instruments. He left the company and then it fell apart – not because he left, but just because it became corporate and the family lost control: the usual American story. He became a stringed-instrument dealer in New York, so he was still in the music world. But I’m the last of that – I think I’m Rudolph the Sixteenth, or something! Time for a change!

Q: So there was no family-business pressure on you.

WURLITZER: Yeah, that was a great blessing. I would have been totally ill equipped for that.

Q: Were you already writing by then?

WURLITZER: I’d started writing when I was 16 or 17. Then I went to Europe for a while, France and Spain. I was in the Army in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, and I wrote while I was there to keep from going crazy – I always sort of wrote. I started publishing some short stories in the ‘60s, and then I sat down and wrote a book, I think it was in the late ‘60s, called Nog. And then I was broke, and Jim McBride asked me to work on a film, Glen and Randa. So I did ‘cause we were friends. He had another writer who’s also a friend, Lorenzo Mans, a great guy, and he and Jim were really collaborators and partners. I came in at a later date, before the shooting, and made my own crazy changes, and so it was a very free-form, kind of hippie-like film. And we were like a commune, in a way. It was great.

Q: Where was Glen and Randa shot?

WURLITZER: Some of it was shot in San Francisco and most of it in northern California.

Q: How would you describe your contribution to the script?

WURLITZER: It was considerable; I worked on every scene. But it was really Lorenzo and Jim who initiated it. It was out of their friendship that it was born. They were the true artistes.

Q: That film begins the tradition in your work of casting musicians or non-actors. That’s been almost a constant in the films you’ve worked on – even without your involvement in the casting process.

WURLITZER: Yeah, it’s funny, isn’t it? It’s funny karma: These musicians swim up and hit my windshield, and I don’t know why!

Q: Is it a preference of yours to try to keep away from professional actors?

WURLITZER: No, no. I think it’s because of the directors I worked with and the nature of our collaboration. It’s sort of off the edge of the ridge in any case; a little bit off to the side of self-conscious theatrical films as vehicles for stars.

Q: How did you come to write the script for Two-Lane Blacktop?

WURLITZER: They were looking for a writer to make Will Corry’s story work as a film, to break it out of, you know, just a Grade B movie. Monte Hellman had read Nog and he called me up and said, “I really liked this book.” Maybe he thought I was just crazy enough to do it! I completely threw out the script they had.

Q: That was the Will Corry script?

WURLITZER: Yeah. There’s nothing left but the idea. It was a great time ‘cause I didn’t know what I was doing, I just wrote. I wrote it in three or four weeks. And I knew nothing about cars. Which was great because my ignorance saved me, you know? It was a kind of innocent time.

Q: The name Floyd Mutrux has come up as an uncredited co-writer of Two-Lane Blacktop. Is that true?

WURLITZER: No. I know that he was around, and maybe his wife then worked in the production. But I don’t remember him doing that.

Q: Neither he nor Will Corry have much of a filmography – Two-Lane Blacktop is Corry’s only credit, and you say it was mostly thrown out.

WURLITZER: It was all thrown out, except for the idea of the trans-country race, and The Mechanic and The Driver.

Q: And the idea of looking at an American subculture?

WURLITZER: Yeah, the subculture: the cars and that world, which was totally Will Corry’s world.

Q: I was curious if you’d been at all involved with it yourself.

WURLITZER: When I was there, I hung out in the San Fernando Valley with all these car freaks. And it was interesting, it was like a new language. So I treated it like an autonomous world that had its own language and its own codes. That’s what drew me in, that’s how I found how to be intimate with the subject.

Q: Is that a traditional relationship, driver and mechanic, as presented in this film?

WURLITZER: Well, I think it is – I mean, not as it’s presented in the film, which is more romantic really, in the whole relationship.

Q: They’re iconic roles.

WURLITZER: That’s right, they’re icons. And I think that the mechanic, especially in racing, is a major part of the team. So there’s a dialogue between those two seminal figures. I just went with that, it was simple, and it seemed so pure. And when you cut them loose from that world, they become even more iconic and mythic and existential.

Q: Hence there are no names for these characters, only titles.

WURLITZER: Yeah, you become part of the dream. It was a very pure filmic idea. I was lucky. It was a gift, there it was, and I was able to write it through.

Q: It was a great intuitive insight on Monte Hellman’s part, that you would be the right person to re-write the Two-Lane Blacktop script.

WURLITZER: Yeah. Monte’s very pure. He’s really interesting. I’ve never worked with a director like him. I didn’t know it at the time, but in retrospect I look back and think, my God, that was a great experience – the least complicated and the most pleasurable.

Q: Logistically, it was a simple shoot?

WURLITZER: Very simple. And very innocent. It was just a magical through line, all the way through. It was like taking it one step further than the old Roger Corman days and really letting the filmmaker be completely free. And of course, when the film was released, it was too existential, too mythic, or whatever, and it didn’t have enough traditional hooks in it. But it still survives. It’s found its due, and Monte is finally being recognized as a pure filmmaker. Monte was great. It was a strange situation because he never showed the script to the actors before they were on the set to shoot the scene. They didn’t know what was gonna happen, and so the script is quite pure because they couldn’t get into it to change it. It was a great experience. Another interesting thing about that film was that no one knew how to end it. It was really Monte’s idea, because any kind of conceptual or theatrical resolution seemed inadequate, and since it was such an existential castaway drift through spontaneous phenomena, the correct and the only way to end it was the way it did end.

Q: A classic line in Two-Lane Blacktop occurs a little more than an hour in, when GTO confronts The Driver and The Mechanic with, “Are we still racin’ or what?” It just sums up the whole film – that his question could even be a question, that far into an American movie about a car race!

WURLITZER: Now with films, the powers that be always want you to tell the audience what they’re seeing, rather than reveal what’s happening. And that’s why you feel so manipulated by most films. Because what are films? They’re dreams. And if you’re being told what you’re dreaming, you’re not dreaming. So where are you? It’s so simple but profoundly dangerous for the money people. They’re all very, very anxious to have scripts and films that they’ve seen before, that are just variations on what worked before. So therefore the films don’t really breathe, or rarely breathe.

Q: In your introduction to the Walker book, you wrote of William Walker himself, “The fears and insecurities that insisted always on avoiding any kind of intimacy would have screamed for him to push on. It would not have mattered where as long as it was toward the margins of civilization, toward those desperate stretches of wasteland where his puritanically rigid nature could breathe.” No one could call A.D. Ballou in your novel Slow Fade or Julius Book in Candy Mountain or GTO or Glen puritans, but this terror of intimacy drives them on too. They all lie about themselves and spiel constantly, and eventually they no longer know who they are. On one level these narratives are cautionary tales, aren’t they? It’s not just whatever material opportunity these characters are running after, which is spilling through their fingers, but the opportunity to have a real life.

WURLITZER: Yeah, that’s true. I never quite thought about it that way, but that’s true. There’s a melancholy cast to them, and a vulnerability and a sense of precariousness about their identity – you don’t quite know if they’re gonna make it or not.

Q: They’re also studies in obsession, aren’t they?

WURLITZER: Yeah, and the illusions of it.

Q: Glen talks to Randa and doesn’t realize she’s wandered off; GTO talks to a hitchhiker without seeing that the person is asleep. You see this kind of frustrated communication in Samuel Beckett, people being alone together.

WURLITZER: Well, Beckett’s a huge influence on me. In fact, he was such a big influence I had to stop reading him, ‘cause he was so great.

Q: You can see it in your second novel Flats – it’s a completely original work, but it still comes from somewhere.

WURLITZER: Yeah, it definitely comes from there.

Q: So does Nog.

WURLITZER: Yeah, definitely. Beckett is great. And Céline was another one, in terms of the road and restlessness, and what it means to leave home.

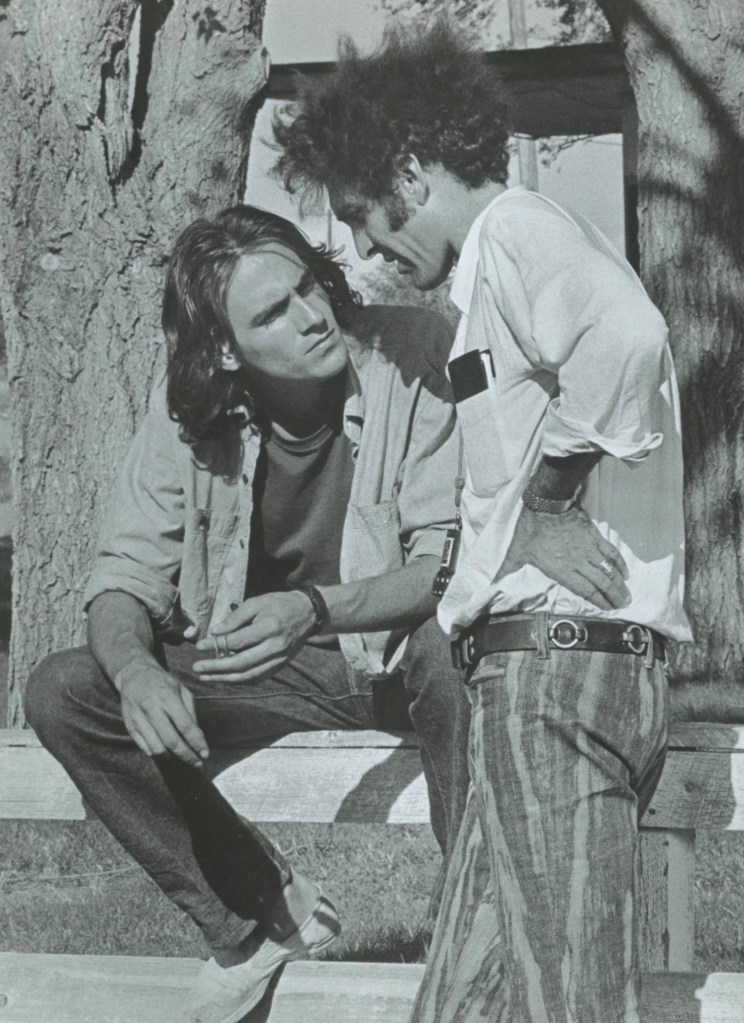

Q: Was it Hellman’s idea to cast Dennis Wilson and James Taylor for Two-Lane Blacktop?

WURLITZER: Yes. It was Monte’s casting. He’d looked around and he wanted somebody who wasn’t an actor, who was innocent and sort of outside the self-consciousness of a proper actor. Laurie Bird had never acted. Other parts were great old pros, like Warren Oates; he was great. That helped, you know, that gave it glue, gave it a different energy. The one-dimensional energy of James and Laurie and Dennis served the film, because it’s an innocent film. I think that’s what’s so amazing about the film. And Monte is very pure and innocent, in a way. That’s verboten now, that’s not allowed now. It was lucky, it was one of those moments. Because it was low budget and about cars, people didn’t really think about it.

Q: Any film that has Harry Dean Stanton making a pass at Warren Oates is always worth seeing!

WURLITZER: That was a mischievous scene. We wanted to wind up Harry Dean! And the thought of those two guys, that was great.

Q: In going to musicians for his casting, Hellman was hiring people who were non-actors but had their own special aura about them.

WURLITZER: Yeah, very definitely, people like Dennis and James were kind of mythic in their own right.

Q: The character of Randa in Glen and Randa is a lot like The Girl in Two-Lane Blacktop: a waif adrift in a hostile world, who doesn’t seem all that concerned about what the next experience might be.

WURLITZER: I never thought of that before. But I think the whole idea, especially in the West, about being an orphan – the West for me has always been a place where you could change your identity, where you could transform yourself. It was the frontier – the cultural, emotional, sexual, political frontier, where all bets were off and you could reinvent yourself. So that’s been my obsession with California – and my disillusion, finally, because now, California is even less of a frontier than here in Hudson, New York! It’s all mono-cultural now. The last book I wrote, which I just finished, Drop Edge of Yonder, is about the Gold Rush. I went back to the early days of California, when it was really chaotic and anarchistic and freeform. Possibly that’ll be made into a film. And that maybe will really close the chapter.

Q: It hasn’t been published yet?

WURLITZER: No, it’s just now being sent out. I didn’t sign up with a publisher because I thought I was going to go crazy writing this book, and I didn’t want people telling me what to do – “Is this commercial? Is it not commercial?” In a way it was risky, because the publishing world is so conservative now and afraid. My type of fiction is very difficult.

Q: You wouldn’t be able to get them to look at something like Nog or Flats today.

WURLITZER: All my older books, I couldn’t publish now. And I’m not even sure I can publish this one. But hopefully with a smaller press, you know?

Q: Pursuing this business of Randa and The Girl a little further: I was wondering if you’d seen girls like that – or boys like that – who just drifted along and were not particularly afraid of things that would have terrified their parents.

WURLITZER: I did, those were the girls that I was attracted to! And that was sort of the way I was. I was just drifting along; I didn’t know what I was doing.

Q: That’s true of a lot of your male protagonists as well, in films and fiction.

WURLITZER: Yeah, the drifter’s a big, big persona for me, a kind of prototype or archetype.

Q: There’s the opportunity not to be attached to things.

WURLITZER: That’s right, and it’s a way to break habits and early imprints and cultural envelopes, to break out of jail.

Q: It’s a sad fact that both Shelley Plimpton and Laurie Bird had such brief trajectories: Shelley retired from the scene not long after Glen and Randa, and Laurie made only a few films and then took her own life. This feeling of something that’s precious because it’s so fleeting, hangs over both films with them.

WURLITZER: Yeah, that’s true. I’d say one of the central themes that haunts me – in general, obviously with my life and also therefore with my work – is impermanence. And how it seems that this country used to be, or still is a song or hymn or dirge to impermanence, you know, that everything changes. Now the acceleration is so fast. That was one of the great promises of this country, and now I think it’s one of the great terrors, because the acceleration and change is so fast.

Q: There’s a loss of identity and meaning because everything is so disposable – anything can be thrown away. Yet again there’s the opportunity to avoid attachment. One of the beautiful things about your films is how they bring a different argument to the table. But at that time in the early 1970s, you weren’t involved with Buddhism, were you?

WURLITZER: No, I wasn’t, not at all.

Q: But the ground was fertile for it.

WURLITZER: Right, that’s true. And it’s not just Buddhist, you know. I think we all are involved in the American crazy phenomena that we live in. This paradigm of reinventing yourself always seemed the great promise of this country. And now it seems deeply threatened. We’re drifting into a totalitarian, post-1984 kind of… It’s deeply disturbing.

Q: Mussolini said that the fascist state was the corporate state, and that’s what we have.

WURLITZER: Yeah, I think he was right. That’s what we have. One of the things that’s wrong with the film business now is that it’s such a corporate endeavor, and films cost so much money. So it’s the lowest common denominator.

Q: For them to invest in a film like Two-Lane Blacktop is inconceivable today.

WURLITZER: The films that I did couldn’t be made now, and the books that I wrote couldn’t be published now.

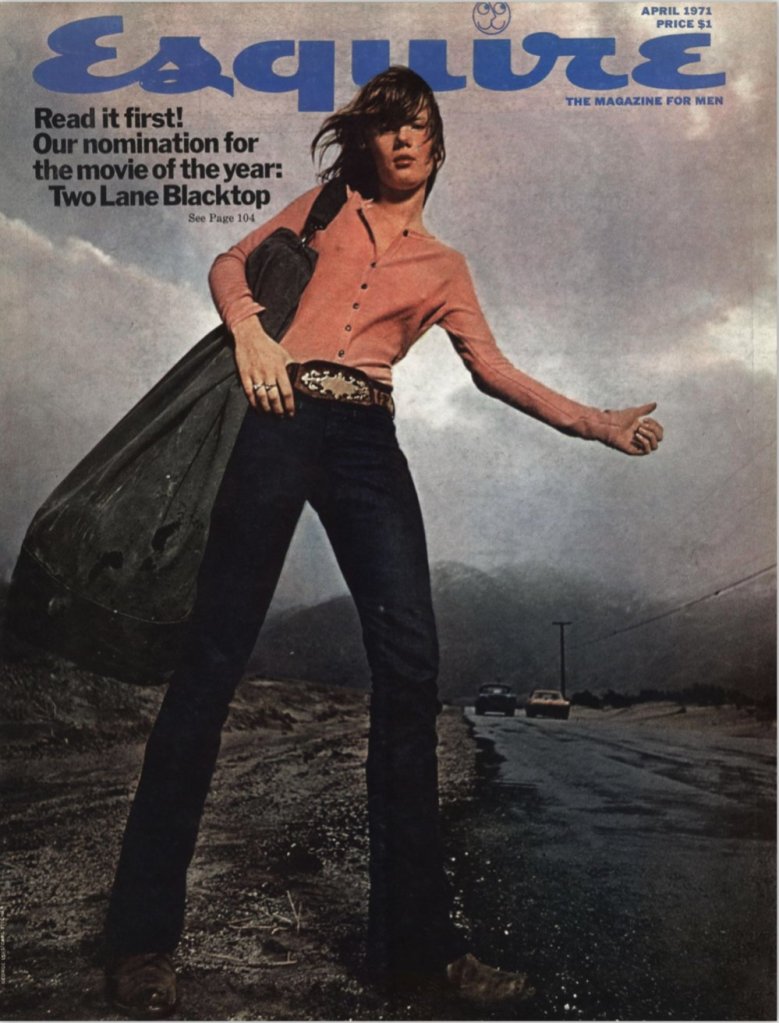

Q: Esquire Magazine swooped on Two-Lane Blacktop before its release and published the screenplay as its cover story; but wasn’t that publicity actually disadvantageous for the kind of film it was?

WURLITZER: Yeah, it was.

Q: What were they trying to do? Were they just showing off that they were ahead of the curve, or was there someone there who actually understood what you were doing?

WURLITZER: I don’t remember who the editor was. They didn’t know anything about films, but they really liked the read, you know?

Q: They’d only read your script and hadn’t seen the film?

WURLITZER: Yeah, it was way before the film was shot. So then, after the film came out, it didn’t turn out the way they’d imagined it would, so there was a certain backlash. But it was amazing they’d published the script. It was lucky. I look back on those days and how one thing seemed to lead to another, and it was all so free form and there were so many interesting wacky individuals involved. It was a golden time and it didn’t last long; by the early ‘80s it was almost over. After every weird novel I’d write, I would be broke, and luckily, people asked me to write a script. Billy the Kid came along and I did that. Then I wrote another book, Quake – which was probably a portrait of Peckinpah in a way, cause he was like being around an earthquake, you know? But he was great.

Q: Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid draws a deliberate parallel between some of the era’s rock icons and the outlaws of the past.

WURLITZER: Right. I really saw Billy the Kid as the kind of outlaw on many different levels. I mean, I saw him as not only just a deracinated kid from Brooklyn, who ended up in the West and became an outlaw, but I saw him as challenging certain kinds of taboos. I saw him as a sexual outlaw. In my first discussions with Peckinpah, I wanted to cast Mick Jagger because there was this great story that I’d discovered in my research, of Billy the Kid walking down the street of a town, completely drunk, dressed as a woman. And I thought, that’s really interesting, we’ve got to make this in the film, this is great, this will really completely insult all the Western fans and it’ll be great! Of course, it insulted Peckinpah! Being an old Western guy, he was horrified! That was the last thing that he wanted and that was the first thing that he cut out. Peckinpah really is a mythic character. I think Pat Garrett was his last film that really was personal for him.

Q: I’ve read that his condition was deteriorating even as he was making it.

WURLITZER: Yeah, he was pretty outrageous through it. But he held it together. I think he was both Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, they were both sides of him: the Pat Garrett side that had to survive in an essentially corrupt world, and hated himself for it, and Billy the Kid, who is pure and innocent even though he was a killer – a kind of Rimbaud figure that, because he was that way, inevitably had to die. I think the scene that was probably most revealing in Pat Garrett for Sam Peckinpah was the last scene, when Garrett’s looking in the mirror. It’s really Peckinpah looking in the mirror and seeing his recapitulation and seeing into the depths of his shadow self.

Q: The Wild Bunch and Major Dundee and Ride the High Country are also concerned with the threat of selling out one’s ideals.

WURLITZER: And those are his best films; they’re his most personal films, when he’s dealing with his own agony and despair and courage, his outlaw self.

Q: Your Billy the Kid script was originally written for Monte Hellman?

WURLITZER: It was, and I always wondered what it would have been like – it would’ve been a totally different film. It wouldn’t have been better or worse, it would’ve been just very different. I think it was purely a commercial choice that the studio and the producer Gordon Carroll went with Sam: They probably thought the film would make more money.

Q: Because of the poor box office of Two-Lane Blacktop, Hellman was eased out of the project and Peckinpah was brought in?

WURLITZER: That’s right, yeah, that’s what my take was. I don’t really know what the back-room talk was, but that’s what I think happened. I was just the humble scriptwriter, you know? I didn’t have any control over it. It’s interesting because Monte, in Sam’s later years, I think did produce a film for Sam. He also helped Sam edit several films. You know, everyone suffers the slings and arrows of the studio system.

Q: Did you have any direct dealings with James Aubrey at MGM during the making of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid?

WURLITZER: One, but mostly it was an ongoing test between Sam and Aubrey. And finally Aubrey took away the editing process. He was a bad guy.

Q: Peckinpah certainly resisted the temptation to make this film fit the pattern of The Wild Bunch or Major Dundee. He understood the kind of script you’d written – and had been a fan of Two-Lane Blacktop, I recall.

WURLITZER: In those brief days, there was an opening for that kind of thing, where you could have original language. Sam did impose a few scenes on the film, cause he had a deal where if he used some of his own scenes he’d get an extra $25 grand or something. So some of the violence comes from an old TV Western of his that he’d dusted off. It didn’t matter because Sam was such a strong crazy character that, in this case, he couldn’t really shoot himself in the foot – the myth and his personal involvement with the story were too deep. He was great. And that’s another case where, at the end of the thing I just left, I couldn’t take it anymore.

Q: You were there for the duration of the shooting?

WURLITZER: Yeah, and I’d actually played a small part in it: the scene at the beginning, where they’re holed up in this shack and Billy gets captured. I’m one of the outlaws and I get killed. And Sam was really happy about killing me! I had to run out the door and get shot and fall over a fence or something, and he kept doing take after take. And he said, “I just love to kill writers!” It was funny. In those days, Sam had his posse, all the old actors like Slim Pickens, that had been on numerous films with him. They loved him and they were protective of him. And they understood him.

Q: You almost never see a bad performance in a Peckinpah film – and that’s a tribute to his casting skill as well as his directing.

WURLITZER: That’s really true, that was part of his talent, his amazing casting instincts.

Q: He brought in Kristofferson?

WURLITZER: He brought in Kris. I think Jon Voight was another person that was looked at – and it was Voight that decided not to do it. I don’t know why he turned it down, but he did. And then Kris came in. Then Dylan came into the film at the last minute, and that changed the balance a bit. He became more of a strange observer, a witness. I had to write his part almost the day before shooting.

Q: I love when he’s reading the labels on the tin cans!

WURLITZER: The thing with Dylan is, if you gave him something that was minimal and concentrated, he could bring his own genius to it and make it poetry, you know? That was how that happened. And how “Knock, Knock, Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” happened was, he and I were riding back to Durango from Mexico City, and he wrote most of it on the plane, on the back of an envelope. He kept saying, “We gotta get a song for Slim, when he’s dying.” So we just laid it in.

Q: You didn’t get a writing credit on Coming Home.

WURLITZER: I didn’t really want it then. Now I wish I had, because it won an Academy Award, but the main writer was Waldo Salt, and I revered him so much. I was a friend of Hal Ashby’s but I didn’t know why he asked me – maybe Waldo was doing something else. And I was very shy about trying for any credit, it would have made me uncomfortable. I never challenged it because I thought it was Waldo’s script; I just rewrote what was already existing. I mean, in my black heart, I would have liked to! It would have helped, you know? But on the other hand, it was correct, I think. If it was now you’d probably get your lawyer on the case, but I’m glad it’s not now.

Q: Can you describe what your contributions were to the final script?

WURLITZER: Let’s see if I can remember. I wrote some of the scenes with Jane in the hospital, and the sex scene, and went through the whole script and turned it up at various places and added some juice here and there.

Q: It was a true re-write; you didn’t just do one or two scenes.

WURLITZER: It was a real re-write. And I was actually writing while they were shooting a lot too. Those situations are always difficult. I really did that for Hal ‘cause I liked him so much. He and I had other things that we were trying to get on but never did. He was another great figure of that era, and it was a privilege to work with him. I miss him. If those guys were around now, I’d still be writing scripts!

Q: Assuming they could get a gig today.

WURLITZER: They probably couldn’t!

Q: After Coming Home you began working on an adaptation of the Frank Herbert novel Dune for Ridley Scott, didn’t you?

WURLITZER: I did that, yeah, and I departed too much – I made some rather radical changes in the book and Frank Herbert was quite upset, to say the least.

Q: Again, sexual unorthodoxy created some trouble: You’d gotten into an Oedipal thing with Paul and his mother, hadn’t you?

WURLITZER: Yeah, I crossed the line! I got spanked on that one.

Q: Can you tell me about the work you did with Michelangelo Antonioni in the mid 1980s?

WURLITZER: We did a film based on a short piece of his called “Two Telegrams.” It was sad because the film was going to get on – it was on, in a way, but he had a massive stroke. Then it was very difficult after that. He kept trying to get it on but he was really limited.

Q: Did he lose his speech after that stroke?

WURLITZER: Yeah. And I went through lots of drafts after that, mostly out of appreciation and respect for him, to keep him active and involved and engaged. We would go and try to get the money, and everyone was too intimidated by him to say no – but they couldn’t say yes either. It lasted for years. But just the other day I got a letter from his wife saying that some French producer wanted to buy the script and they would probably sell it to him. Who knows?

Q: How did you first get together with Antonioni?

WURLITZER: He came to New York looking for a writer to work with on this, and I was recommended to him. David Mamet was another guy that they were thinking about, but I think Mamet wanted more to do his own thing. And I was so honored to work with him, you know, to be around him and see how he thought. He was a sort of a deity for me, so I couldn’t say no. It was a long difficult project that was very sad. But he’s amazing, I mean, he’s like what, in his mid 90s and he’s painting.

Q: And these short films of his were just made recently; apparently his wife functions as a go-between when he films.

WURLITZER: Yeah, she’s an extraordinary woman, totally devoted. She’s been amazing with that whole process with him. It’s a profound and complex love story, their journey together. It hasn’t been easy but it’s been extraordinary. She’s courageous.

Q: You acted for Robert Downey Sr. in his film America.

WURLITZER: That was fun. I love Bob Downey, he’s a good friend, he’s great. I never saw it, but it was fun. He was in one of his crazier periods, so it was really off the wall. I have nothing but great feelings about him. He just did a wonderful documentary, Rittenhouse Square; it’s really sweet and totally wonderfully relaxed and without forced guile. I think that’s what he’s doing now, working with in that way – I think he’s like me, burned out with this… But he’s great, he’s still doing it, you know? He’s amazing.

Q: Besides Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, you also acted in Two-Lane Blacktop and Walker. Was there ever a point where you wanted to do more acting?

WURLITZER: No, I prefer to be behind the lens. I’m not an actor – I look very nervous!

Q: How come you didn’t give yourself a little part in Candy Mountain?

WURLITZER: I would have but I was co-directing it, so that it was a complicated exercise, and I had my hands full, psychologically.

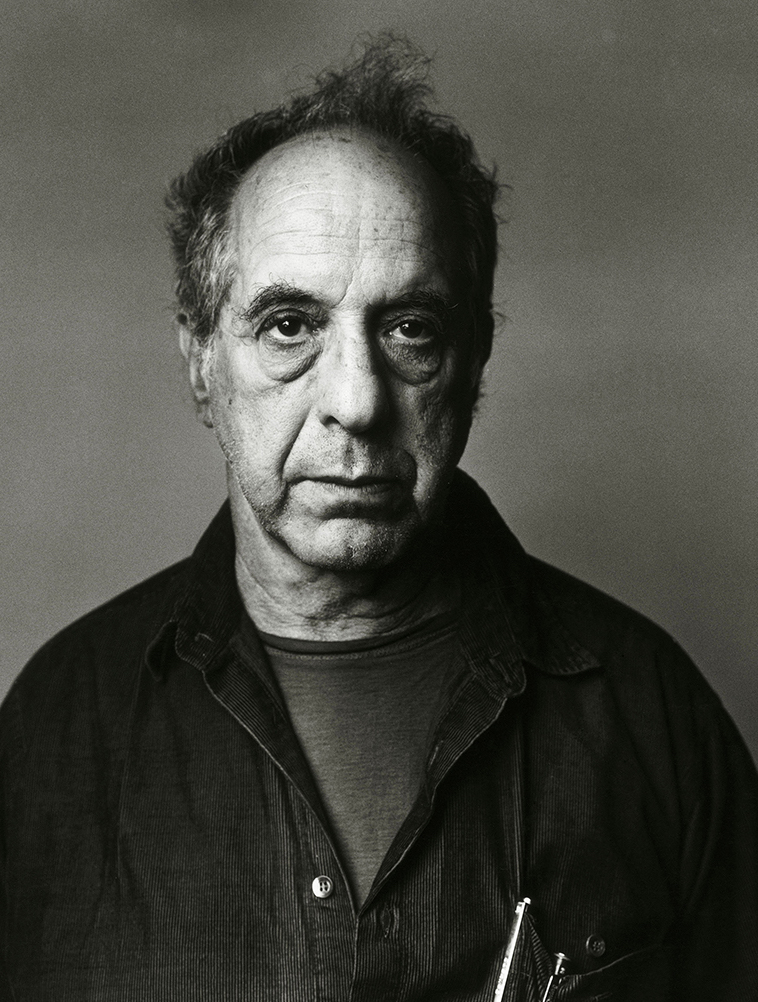

Q: Could you explain the different duties between yourself and Robert Frank in co-directing that film?

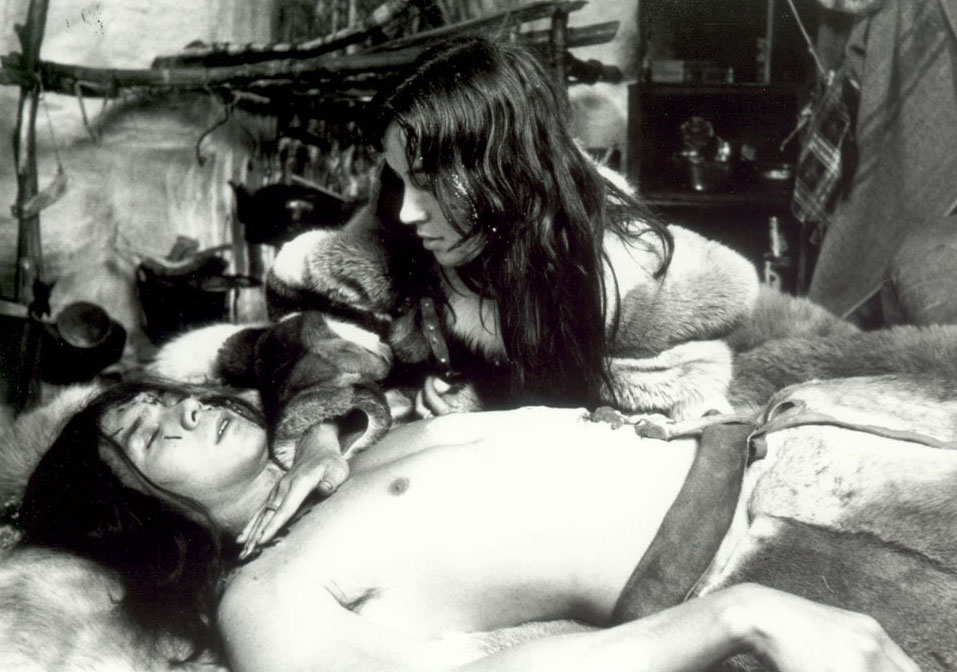

WURLITZER: Basically, having two directors is impossible. We went through the casting together, the locations, and we shared a lot together in terms of how the film was conceived and how it was originated. We both have places in Cape Briton where it was shot, and we had both worked together on two little films before that. And it was obvious that Robert had to control the visual dynamic of the film, and in a sense my role was difficult. I had to sublimate myself to how he worked, so it was difficult. But we got through it.

Q: Was one of you more involved than the other in working with the actors?

WURLITZER: You know, that was such a low-budget film, and there were so many set-ups, and always in a different location – we did go over it with the actors and rehearsed before the scene was shot, but not nearly as much as most films.

Q: There are a lot of the non-actors in the cast, and if you rehearse them too much you can lose what makes them interesting.

WURLITZER: No, you just go. And Robert’s sort of genius is that he’s one who lives best in the spontaneous moment. He always tries to find the original moment, the unstudied moment.

Q: It’s a still photographer’s sensibility.

WURLITZER: Yeah, exactly. But this film, I think, was difficult for him, because even though it was a really low-budget co-production, it was by far the biggest film he’d ever been involved in, with set-ups and location managers and art directors, stuff that was alien to him. So we did without as much as we could. He’s a very intimate person, and so his choices were always for what was most intimate. The beginning of the film, the New York part, is the most problematic for me; then, as soon as we got out on the road, things started to work, and the Cape Briton part, the Nova Scotia part, for me is the most satisfying and authentic part of the film.

Q: Had you written the script with the idea that it would be your vehicle to become a director?

WE: No, I just wrote it. I never thought of it that way. It was a collaboration and it was about our friendship – we’d taken a lot of road trips together. I didn’t project anything but itself. It was enough just to do the fucking thing, you know, to get through it. I actually, really just thought about surviving it. I didn’t have ambitions past that. We didn’t even know if it would get distributed.

Q: There’s no American money in Candy Mountain, it’s a Canadian-French-Swiss co-production – it could have been ignored completely here.

WURLITZER: That’s right, yeah. That’s another film that couldn’t be made now.

Q: Did Frank approach you about sharing the direction?

WURLITZER: Yeah, it was always sort of understood that it was a collaboration: I would do the writing, he would do all the visual part of it, and somehow we would be in agreement enough not to go at each other! We had a few moments and it was difficult. One had to swallow one’s ego at times. You had to serve the film to get through it. But I would never do that kind of thing again, I would never direct with anyone. Because it doesn’t work really, basically – even though I like the film and I’m glad we did it. But I’m too internal a person. I was tempted to direct several times, and almost did, but I was scared about what would happen to me. I didn’t trust myself, I was afraid I would become too self-inflated. And I didn’t really like that aspect of my character, the manipulation part of it, the dictatorial part. That’s what most directors feed off. The part of me that was attracted to it scared me. I thought, “I’m not sure that I want to go down this road.” And I often wonder about that, because there are times when I think I should have; I should have taken it on and seen what would happen. If I had it to do over again, I might. Even though I don’t think it would have been that great for me. I mean, it’s so toxic, it’s such a loaded thing to do. And I didn’t trust myself. I thought there was a part of me that maybe wanted it too much.

Q: Has this train left the station, or might you still put together a project that you would direct as well as write?

WURLITZER: Maybe, but probably not. I’m so off the grid! Somebody would have to come into the kitchen and say, “Would you do this?” And I don’t think that’s gonna happen! First of all, they don’t even know if I’m alive! “Is he still around? Oh my God!” If you’re over fifty….

Q: Candy Mountain is a dream in terms of the casting. Was the casting handled by both you and Robert Frank, or did you have certain actors in mind as you wrote the script?

WURLITZER: I think people’s names came up, you know? Like I always thought that Dylan would have been great. We had names that we thought of, that couldn’t do it for one reason or another.

Q: Besides the musicians, Candy Mountain has all these wonderful character people like Rockets Redglare and Roberts Blossom and Mary Margaret O’Hara. The film seems, on one level, to be a forum for talent like that to do its thing.

WURLITZER: Yeah, that’s the kind of world and culture we lived in. In those days we were very friendly with Jim Jarmusch.

Q: Is it true that he was in the film but got cut out?

WURLITZER: Yeah, not because of him but just because the scene didn’t quite work. But he had a subtle influence on the tone, all down on the Lower East Side. We also had a casting director that was in tune with our world. Rockets Redglare was a friend of Jim’s, and Robert Frank is this iconic figure down there, so people always wanted to work with him. Tom Waits was somebody who’d worked with Jim and was a friend. I knew Dr. John and that wonderful woman, Rita MacNeil, who sings at the end – she’s very famous in Cape Briton, a local Canadian singer.

Q: Harris Yulin is another very underrated talent.

WURLITZER: We considered a lot of people for that role. We wanted somebody that was very grounded and solid at the end of the film, that could hold and be a little bit perverse. So he came into it. We had thought about other people for that, but they weren’t available. And Harris, he was fine.

Q: His character has a lot in common with the director Wesley Hardin in your novel Slow Fade: An authority figure who no longer wants the authority and is looking for a chance to sell out.

WURLITZER: That’s right.

Q: Which puts the final lie to the quest that he’s been pursuing.

WURLITZER: Yeah. Part of the journey, part of the conceit, if you will, is to continually pull the rug out from what you think you’re going towards or what you’re projecting. It’s always something else that happens, you know? Julius in Candy Mountain has this one obsessive goal, to find this guy and make some money off it or become famous, and what he finds is the opposite of what he was looking for, which is often what happens, isn’t it? Isn’t that what the journey of life is often about?

Q: He undergoes a dismantling process, as his resources are stripped from him during this journey. And at the end of the film, when Julius is penniless and hitching a ride, you’re left wondering if perhaps now he’s a better person.

WURLITZER: One hopes that he’ll learn something and that that experience will season him in a way; that he hasn’t lost too much of his innocence, but will have lost some of his naivety and his profane ambitions.

Q: Some of his illusions.

WURLITZER: Yeah, so he’ll be more in the moment, rather than driven toward some conclusion that doesn’t exist in the first place.

Q: This quality in your work reminds me strongly of the novelist Nathanael West.

WURLITZER: Yeah, I love him.

Q: There’s a straight line from The Day of the Locust to Quake.

WURLITZER: Yeah, that’s very much L.A. I always wanted to make Quake into a film. And now it would be even better, you could do it now.

Q: When Walker’s brother is shooting people during the burning of Granada, I’m reminded of Quake and the insane militia that takes over after the earthquake.

WURLITZER: That’s true, I hadn’t thought of that.

Q: A catastrophe letting out the evil in people.

WURLITZER: All the demons can come out of the jar. You can say that it was the unconscious bursting forth, and the demons come out. That’s what’s happening now, isn’t it, in this culture?

Q: Is there a chance that someone will make available the two earlier films you made with Robert Frank, Keep Busy and Energy and How to Get It?

WURLITZER: I think a museum in Houston owns the rights to Energy and How to Get It, which is the best one. And what they do with it, I don’t know. That’s a strange little film. It’s about this mad inventor who is in this town in Utah; he’s about 45 and living with a woman 75 or something like that, and he was a disciple of Tesla’s. So we went out there and filmed him. I wrote the script as it was filming; we sort of improvised the whole thing as it was happening. William Burroughs plays an energy czar! It was good. It was a lot of fun doing it. I haven’t seen it in a long time. I don’t know how it would hold up, but it was very good at the time.

Q: There are odd prescient things in your work, even down to the prominence of Hudson on the New York State map that appears on the video box of Candy Mountain!

WURLITZER: Yeah, go figure, that was before I even knew Hudson existed!

Q: In Slow Fade Walker loses his wife to a snakebite, and a few years later you adapt the Max Frisch novel Homo Faber, which also involves such a death. And there’s that moment in Candy Mountain when Julius falls asleep behind the wheel of the car – which is how your stepson lost his life in 1992.

WURLITZER: That’s true, yeah. You don’t know what you’re unlocking. That’s why I’m always terrified of – you know, my inclination is towards a certain unfortunate kind of nihilism. It’s an old habit that I feel deeply ambivalent about, so now I’m very self-conscious about how to end something. I don’t want to have everyone fall off the cliff, ‘cause I know I’ll be coming right after them!

Q: A Tucson unit is credited in Walker. The whole film wasn’t shot in Nicaragua?

WURLITZER: It was all shot in Nicaragua except for the scenes with Vanderbilt. They were shot in Arizona with Peter Boyle. Universal is really afraid to release that film, I suspect for political reasons. They would probably say no, but I think they’ve kind of taken it off the shelf, and that’s really too bad, ‘cause it should be in the conversation. But it’s too radical for this culture right now.

Q: In a funny way, the film has fallen victim to the curse Vanderbilt attaches to Walker himself: “No one will remember him.” People who discuss William Walker find themselves wrapped in obscurity. There’s an almost willful refusal in this country to be aware of who he was and what he did.

WURLITZER: No, they don’t know about him at all. It would be so great to show it now! Bush’s middle name is Walker, right?

Q: That’s the W in Dubya, all right! I find that films which use anachronisms tend to be received harshly by the critics.

WURLITZER: The anachronisms were Alex’s idea. They weren’t in my script.

Q: But wonderful things like Walker on the cover of Time Magazine, they go down so effortlessly. Far from diluting the story, they provide the perfect touches.

WURLITZER: Yeah, that was his skill at improv, that’s what makes it interesting to see now.

Q: At that time you were saying extremely positive things about working with Alex Cox.

WURLITZER: Yeah, I love Alex, Alex is great. He’s one of the few people I’d like to work with again.

Q: You’ve told me that he was feeling you out just recently about a new project.

WURLITZER: Yeah, there’s one idea that we have that could be shot here in Hudson. I could stay at home! It would be nice. If I ever write again, maybe I’ll get to write the script.

Q: What do you think the problems were that derailed his career here in the States?

WURLITZER: I think he’s a real true original. I think he’s fearless and he perhaps picks fights that he shouldn’t. He should be working. He’s a unique character, really talented, really smart, and fun to work with. He just had really bad luck with the powers that be.

Q: A lot of musicians also turn up in the cast of Walker.

WURLITZER: Yeah, Joe Strummer was a friend of his, Dick Rude was a friend of his. Yeah, his casting is always original. The cast was great.

Q: Was Ed Harris the Walker you envisioned?

WURLITZER: Yeah, I thought he was brilliant, I thought he was fantastic. He was inspired, totally concentrated and maniacal.

Q: An extremely difficult role too.

WURLITZER: Really hard. I thought it was a great performance.

Q: The Walker book details how Nicaragua, despite having no infrastructure or amenities to support a film crew, was actually a very cheap and efficient place to shoot.

WURLITZER: Really cheap. It was a great place to make a film.

Q: Nobody was treated with hostility down there for being American?

WURLITZER: No, not at all. One of the great experiences I’ve had was being there and making that film. It was a real privilege.

Q: Your presence there was itself an act of solidarity with Nicaragua.

WURLITZER: It was, that’s why we did it there. Alex was completely insistent on it, he wouldn’t have done it anywhere else.

Q: He’d been down there before and seen the possibilities.

WURLITZER: They kept saying, if you want to do something for us, why don’t you do something? Walker was his idea. He came up with the idea, and it was a very courageous film to make. And sometimes you have to pay a big price for doing something courageous.

Q: It’s appalling to think that a studio could back a film and then be afraid of it when it’s completed.

WURLITZER: Yeah, they just pulled back.

Q: And then there’s nothing to be done.

WURLITZER: No, they own it.

Q: It received such scant distribution that now it’s become a cult film – as have several other films you’ve worked on.

WURLITZER: Yeah, Mr. Cult Film. I wish I had one that wasn’t a cult film!

Q: But none of these films are obscure, or different for the sake of being different. It’s always about the story.

WURLITZER: Yeah, I never think, “Oh, this is a cult film.” I always think, “Wow!” I just think of the story and let it fall where it falls.

Q: Are you an uncredited co-writer of the Burt Reynolds film Malone?

WURLITZER: Yeah, I did quite a bit of work on that. I never saw the film, but the English director was Harley Cokliss and it was shot in British Columbia and Vancouver. It was a gig, you know? I can’t remember too much about it.

Q: Were you brought in just to do a re-write, knowing that you wouldn’t get a credit on it?

WURLITZER: Yeah, a wash and rinse!

Q: Were you at all involved with Christopher Frank who wrote the original script?

WURLITZER: No, never met him.

Q: What struck me about the film is that it’s a Western, only set in the present and without horses!

WURLITZER: That’s right, it is!

Q: It’s a funny tribute to the durability of that kind of storytelling.

WURLITZER: That’s true. I hadn’t thought about it, but that’s true. Wow – I haven’t thought of that one since I worked on it!

Q: Right around that time you told Film Comment magazine, “I’ve been scarred up by Hollywood.” Were you thinking especially of the projects that couldn’t be realized, or was it more the general ignorance and greed and cruelty there?

WURLITZER: Yeah, the whole thing, the whole display. It takes it out of you. The writer is always in such a precarious place. There’s always a desperate struggle to preserve your integrity and autonomy, in an essentially collaborative medium where you don’t have any real power. So you’re at the mercy of who you’re working with. And as films became more and more expensive and global, the individual is diminished. So it became more cruel, in the way corporations are cruel. It’s very hard now to go into a meeting and have to do a song and dance to sell the idea for a script, when there are four or five marketing people in the room with the producers. I can’t do it. For me, the act of writing is an act of discovery, and so I get sort of perverse – I don’t want to tell the whole thing because it sort of destroys it for me. By the time you sit down to write, you’ve gotten all these notes about what kind of a film it should be and where it’s going – and then why do it? It just becomes a kind of agony; it just gets harder and harder, the more you do. That’s what I meant about getting beaten up. You lose sight of your unconscious and you lose sight of why you’re a writer in the first place. It’s not about money, it’s about the journey of finding a story that resonates in the deeper levels of your psyche. When that’s taken away for openers, you get damaged. So you have to run away. What finally destroyed Peckinpah was the nature of the enemy. He was no longer fighting a Jim Aubrey or some profane producer, he was fighting the corporate impersonal system, and that’s what robs you of your soul. He couldn’t breathe in that, and I can’t either. The corporate reality of the system destroys you, it’s much more lethal, because you’re destroyed before you get in the room.

Q: And there’s no shirt collar to grab and yell, “You S.O.B.!”

WURLITZER: No, there’s no bad guy. Everyone’s very pleasant!

Q: But all the humanity’s been taken out.

WURLITZER: Yeah, and all the passion and the spontaneity and the creativity. Endless notes from people who know nothing about films or the creative process, all about how to make a film as accessible to the most amount of people and attract celebrity stars. It’s deadly. It’s no fun.

Q: No fun to see those films, either. It all seems terribly ersatz.

WURLITZER: It is, so one doesn’t even go anymore, you know?

Q: Trying to penetrate the conventional Hollywood scene to do creative work just doesn’t seem sensible. It’s like trying to teach your dog to dance the polka.

WURLITZER: Yeah, it’s not possible. It’s so futile, you know? It’s an interesting strategy as you get older, to try to figure out how to keep going and not be stuck in the waiting room – a very bad place to be!

Q: By the late ‘80s, most of your career in film is with European productions.

WURLITZER: Yeah, I found myself having to go to Europe to work. Europeans are difficult in other ways: They don’t pay you; they don’t really treat you as well as you might think; you’re not protected at all, you’re not in any writers guild. So it’s difficult too. But there are also people like Volker Schlöndorff who is an immensely talented individual and well read. He has tremendous respect for writers and the creative process, and is very brave in his way.

Q: Did he approach you to adapt Homo Faber into the film Voyager?

WURLITZER: He did, yeah. But even he has trouble. I don’t think he could work in this country again. Maybe he could.

Q: It would have to be something very marketable.

WURLITZER: It would have to be a different thing than he does. But Europe has become like this country now.

Q: The Julie Delpy character in Voyager is related to both Randa and The Girl in Two-Lane Blacktop.

WURLITZER: Yeah, she was sweet and innocent. That was an interesting cast.

Q: Sam Shepard gives a very good performance.

WURLITZER: He does. Sam was great, I think this is one of his best performances. He was really good.

Q: Did you write the film solo or co-script it with Schlöndorff? I’ve seen it credited both ways.

WURLITZER: In this country, I have the sole credit, but in Europe, you know, it’s the “auteur”! I prefer to go with the credit in this country.

Q: The only American production you’re involved with during these years is Wind.

WURLITZER: I forgot about that one too! That was another re-write. That was a very difficult film. There were lots of scripts.

Q: A slew of writers are credited on it.

WURLITZER: There was about twenty, I think. I did most of it, but finally I couldn’t continue because the director was very difficult with writers – as often happens with cinematographers who direct: They have trouble with language. He could never make up his mind about what he wanted. I worked hard on it but it wasn’t a satisfying experience.

Q: Judging from the film, Ballard just wanted to tell an old-fashioned story built around competitive sailing.

WURLITZER: Yeah, that’s right. It was all about sailing, and everything else was kind of sublimated to those images.

Q: It’s beautiful to look at.

WURLITZER: He’s a great cinematographer. He has a great eye.

Q: Francis Coppola was executive producer of Wind. Did you have any involvement with him?

WURLITZER: There were a couple of meetings where he said some very smart things – be careful not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. But Carroll was on his own track and compulsively changing things all the time. So finally you didn’t know which end was up or what was real and what wasn’t. It was a very difficult experience.

Q: A lot of writers are also credited for Shadow of the Wolf.

WURLITZER: That one, I did the first drafts. The director was very insecure and in fact shot the whole thing on a set in Montreal. He couldn’t handle the Far North. So he lost touch with what was original and unique about what that story could have been. And that wasn’t a good experience either. I just walked away.

Q: There’s not much anyone can do with Jennifer Tilly and Lou Diamond Philips as Inuit, but there are some very powerful moments in that film.

WURLITZER: Yeah. I liked a lot of the script I wrote for that. I was sorry that they compromised it; it could’ve been a good film.

Q: There’s a line in that film, which made a great impression on me: “We must go on living and wait for the white man to change.” As an openly queer person living in this country, I have to go on living and wait for straight America to change.

WURLITZER: We have to go on. There’s such a temptation to be negative and apocalyptic and despairing, ‘cause we really live in a pit of darkness. But all the more reason why we have to, even if it seems against the grain, we have to be positive, be as light as we can, be as generous as we can, because the times demand it. And the darkness is very seductive. I mean, the common ground for most conversations now is, how awful it is. But that’s all the more reason to be generous and to be communal and to be – even if it seems crazy – to be positive.

Q: Because the alternative isn’t simply annihilation, it’s assimilation – into a way of thinking and being and relating which is repugnant and delusional.

WURLITZER: And dangerous. You feel at times that the whole planet is endangered, and who knows what’s gonna happen?

Q: Little Buddha describes a whole other approach to relating to the world and recognizing delusion; but you’ve written that the experience left you with “burn-out and self-recrimination.”

WURLITZER: It was very hard for me. Maybe it’s not really fair because I probably knew too much and not enough about the subject and what it could have been. I think the director took the easy way out. You know, I’m probably the wrong person to ask about that film, because people tell me that they really like it and that it’s positive and the kids like it. But from where I am, I see that it could have been so much more, it could have really taken on more. As it was, though, I think it took on about as much as the people involved could take on. So I choose to be positive!

Q: Did you write with Mark Peploe?

WURLITZER: No, I did the whole script. He actually did very little on the end.

Q: He’s Bertolucci’s brother-in-law, isn’t he?

WURLITZER: Yeah, and he comes in on a lot of his films. I don’t think what he did helped it at all. But it wasn’t much. I reached a point where I couldn’t go on, and then my stepson was killed and so that was it for me. It was a difficult passage.

Q: Were you more involved with the American story or with Siddhartha’s?

WURLITZER: I was probably more involved in the Indian and Nepalese part. But as happens with some European directors, I don’t really think Bernardo’s that skilled or comfortable with this country, and I think the American part is the weakest in some way. But you can’t do anything about it – these maestros are gonna do what they do.

Q: Had that always been part of the film’s concept, to combine present-day Americans with a religious story of the past?

WURLITZER: Yeah, I think that was the hook for a Western audience, which Bernardo felt was necessary. I think he kind of hid behind the fairy-tale element, the children’s story. And the film lost its edge, it didn’t risk being dangerous. Because it is a dangerous idea: Siddhartha taking that journey, leaving home and abandoning his wife and going into the jungle and confronting his demons. It was fraught with issues and dilemmas that were very difficult to make simple for an audience and make it play without making it simple minded. That was probably in some ways the most difficult experience I’ve had – and I’ve had a lot! It was a brave thing for him to try to do, and there are some things in it that I think are probably good. But he was out of his element in the East – although I must say that the film he did in China, The Last Emperor, was great.

Q: Did you receive any negative feedback from Buddhist groups here in the States, who thought you misrepresented the faith?

WURLITZER: It didn’t affect my life, but I’m sure a number of them did. That doesn’t really bother me. They’re deluded too. You know, people that are on a certain path are rarely satisfied with what their perceptions of something could be, including myself. But I live such a reclusive life… And you know, movies, like dreams or like newspapers, they fade away. People can’t quite remember, you know? Which is fine.

Q: Is it true that you had been working on an earlier version of Ghost Dog with Jim Jarmusch?

WURLITZER: That’s a bad story. I had worked for a long time on a script that I was gonna direct at one point, a Western called Zebulon. Jim was interested in it and we worked together for a few weeks until it was clear to me that we just saw it in different ways, and so we didn’t continue. But then he took my story and made it into his own and I was very upset by that. A lot of it was quite, quite similar to my script, and I even thought of doing something about it. But then the film was already made, and it’s just not my nature: It seems totally futile and past the point to go to court about it, because everyone loses – except the lawyers. And then you think about it too much, and it contaminates you. So you just let it go. But that was a tough one, because I worked many, many years on that script. It went through many, many changes with different people being involved in it. But this book that I’ve written, Drop Edge Of Yonder, reclaims a lot of it. Maybe it’s for the best.

Q: I was going to ask if you tried to salvage the material in some way.

WURLITZER: I could never do it as a script, the script was ruined for me. He took the essence of the script and I could never, never get back to it. But that’s show biz!

Q: Had you an advance word that Jarmusch had done this, or had you not known until Ghost Dog was released?

WURLITZER: I didn’t really know. No, I was quite shocked and I went into a kind of depression over it. Other people too, that were involved in it.

Q: They’d lost their shot with it too.

WURLITZER: Yeah, he had taken it, co-opted it. I mean, I’m sure he feels he has his own way of rationalizing it, but… Anyway, they’re all just dreams, aren’t they? Some work out and some don’t.

Q: I was fascinated to see that you’d written the libretto for Philip Glass’ opera on the Franz Kafka story “In The Penal Colony.” How did that project come together?

WURLITZER: Well, Phil and I are old friends, and we’ve always wanted to work together. So we did and it was a good experience. I’d like to do another one with him. It played in various cities in Europe, and here in New York and Seattle and Chicago. It’s a small piece so it can travel easily.

Q: Did you have to invent Kafkaesque material, or was it more a matter of shifting what he does into this different medium?

WURLITZER: I think my libretto was very true to Kafka, and I used him as much as I could.

Q: He’s a character in the opera, isn’t he?

WURLITZER: Yeah, but I didn’t write that. That was introduced by a director, which was upsetting to me cause I didn’t think it worked. But the European versions, when different directors come in, they don’t use that. That’s the great thing about doing a stage thing, you can get another shot! It’s not frozen on celluloid.

Q: Is the Shinobi script in turnaround, or might it become active?

WURLITZER: I heard from the producer: That almost got on in L.A., and then the studio that was doing it went belly up – I can’t remember the name, a small studio. Now the producer says that he wants to do it in Japan and direct it himself as an independent Japanese film. We’ll see. His name is Mata Yamamoto, he was one of the producers on Wind. And he’s a real character, so who knows? With the Japanese you just don’t know.

Q: I’ve read that someone named Stuart Beattie was doing a re-write on your script.

WURLITZER: Yeah, but now he’s gone back to my original script – so he says. I don’t know, the company that owned it for a while sort of dumbed it down a bit.

Q: It may have more luck as a Japanese production than as an American.

WURLITZER: It would be better. It would be a more interesting film, certainly. I hope they do it, but I haven’t heard from him in a while. I hear from him every six months, saying, “Yeah, we’re doing it, I’m translating it into Japanese, and we need to get together and work on it.” And then six months go by! I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about it.

Q: “100 Centre Street” gave you an opportunity to write for television here in the States.

WURLITZER: Alan Arkin is a friend of mine – he’s the one that got me to do it. That was fun because it was for Sidney Lumet, and he’s great. It was wonderful to sit down and write an episode, take it in to Sidney, and then he would shoot it. So I thought, “Wow! This is great!”

Q: He has a co-script credit on a couple of them. Did you write with him or did he change some things?

WURLITZER: I think some of them were his original ideas. But you know, the great thing about that process for me was Sidney, and that there was no ego attached. I just was happy to be part of the process, and whoever worked on it was fine. I didn’t feel anyone was ruining my golden words! ‘Cause TV is a different medium, I never did anything like that. And I only did it for a short time. It was just a unique set up with a very good vibe. And Sidney is really gracious and inspiring to work with.

Q: What’s been the biggest disappointment in terms of trying to get a project off the ground which just wouldn’t happen? Was it adapting Slow Fade?

WURLITZER: That was difficult. I did that for Alex Cox and he couldn’t get it on. Some English people recently asked me to do it, but I don’t think they will. No, the hardest was that Zebulon thing. I worked so many years on it, and was gonna do it myself. Hal Ashby was gonna do it at one point, and he died, unfortunately. Richard Gere was involved with it for a while. Lots of people were. It just was one of those doomed projects. That was the hardest ‘cause it took the most out of me, it happened over many years. Another lesson in something. I just guess you have to let go. You can’t hold onto these things.

Q: Maybe there’s some way to publish that script.

WURLITZER: I’ve been asked to put out some of my scripts that didn’t get made on the internet and I might do it, just for the hell of it. It’s a brave new world – I don’t know much about it!

Q: Alex Cox said that you had been developing another script to be shot in Nicaragua.

WURLITZER: We did two other scripts together. One was called Zero Tolerance, part of which could have been shot in Nicaragua; maybe he was referring to that. Then we did another one called Body Parts, which is about an evil doctor in Mexico, who’s stealing body parts. But neither of those got on. He was probably referring to Zero Tolerance, which was a really political film. Somebody recently asked about Body Parts, but I don’t know – I don’t even have an agent anymore!

(This interview, conducted on June 27, 2005, in Hudson, New York, appears here for the first time.)

Link to:

Film: Interviews: Contents

For more on Philip Glass, see:

Music Book: Soundpieces: Interviews with American Composers

Music Lecture: “Intense Purity of Feeling”: Béla Bartók and American Music

Music: SFCR Radio Show #32, Riley, Reich, and Glass