Purists of Elizabethan drama condemned filmmaker Derek Jarman to their proscribed list after his rowdy adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. His latest film, taken from Christopher Marlowe’s tragedy Edward II, won’t win him any new friends in that camp, but for audiences eager to see how a play written circa 1592 can speak directly to the political, sexual, and psychological turmoil of circa 1992, Jarman’s Edward II is a landmark.

Edward II, England’s king from 1307 to 1327, dutifully married Isabella, the sister of the King of France, and fathered a son, Prince Edward, who would succeed him after his death. But the great love of his life was Piers Gaveston, the companion of his youth. After Edward’s assumption to the throne, his passion for the lowly born son of a knight was regarded with horror by the nobles of his realm, who ultimately rebelled against the king, made him surrender his crown, and had him executed. Reportedly dispatched in such a way that the body would be unmarked, Edward’s murder – a red-hot poker thrust into his anus – sums up the psychotic loathing with which heterosexual society regarded the king’s homosexuality.

Marlowe was careful to depict Edward’s fall as a combination of circumstances: The king’s sexuality would have been more easily tolerated had he kept it hidden or at least chosen his minions from the ranks of the nobility. But his commitment to Gaveston, upon whom he bestowed titles and honors normally reserved for the upper class, proved to be his undoing. While not ignoring the classism Marlowe exposed, Jarman focuses more squarely on homophobia as the ultimate cause of Edward’s downfall: The civil wars provoked in the nobility’s attempt to dethrone Edward are played as gay rights protests against helmeted police. (Britain’s recent Poll Tax riot is also evoked here.) Jarman has similarly refined the play’s narrative structure to good advantage. Marlowe’s tragedy is notoriously hard to stage because the characters’ alliances, successes, and failures constantly reverse themselves with such lightning speed as to strain dramatic credibility. Jarman’s film creates a potent sense of a gathering, inevitable catastrophe through a judicious cutting and rearranging of the text, but still retains the play’s fundamental atmosphere of chaos and instability. When Annie Lennox turns up to sing Cole Porter’s “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye” for Edward and Gaveston’s enforced separation, what resonates most is her repeated refrain, “How strange is the change from major to minor.”

Jarman’s decision to go Eurythmic in the middle of his tragedy is as happy – and appropriate – an inspiration as Elisabeth Welch’s rendition of “Stormy Weather” for the finale of The Tempest. But such humorous additions, like the occasional deliberate anachronisms of Jarman’s Caravaggio, have been elevated into a new narrative discourse in Edward II. The film is not a “modern-dress” version of an Elizabethan play, but rather a contemporary indictment of homophobia, classism, and political control, spoken almost completely in Marlowe’s poetry, just as Jarman’s non-narrative film The Angelic Conversation used certain sonnets of Shakespeare to provide all the verbal commentary needed in a welter of aesthetic and homoerotic imagery. Eschewing the rich canvases of film textures and treatments, which are the glories of The Angelic Conversation, The Last of England, and The Garden, Jarman’s Edward II employs more uniform visual tonalities and is restricted to stark, elemental sets with only a few, mostly contemporary props for punctuation. But the film is a tour de force in maintaining visual interest and complexity through Jarman’s unconventional use of time (Edward’s imprisonment with his executioner is intercut throughout the film), his painterly sense of lighting and color, and his freewheeling admixture of past and present.

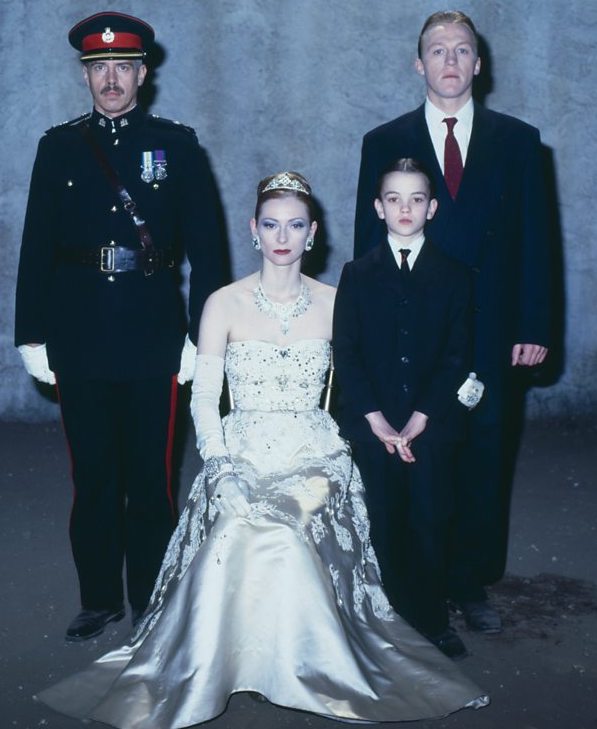

The casting is uniformly excellent. Steven Waddington has a finely honed sense of both the joys and miseries of the tormented king, and is able to keep the character consistent throughout the ups and downs of his tragedy. As Gaveston, Andrew Tiernan displays a splendid feral quality, perfectly evoking the commoner’s perverse urge to flaunt his position in the faces of the nobility. Nigel Terry’s Mortimer, although not the multi-faceted creation his Caravaggio was for Jarman, is persuasively ruthless and fearsome as the noble who ultimately dethrones the king. Jerome Flynn, as Edward’s brother Kent, and Jody Graber as the king’s young son, are equally effective in their roles. But top honors must go to Tilda Swinton as Queen Isabella, Edward’s despairing wife. This remarkable actress, so memorable in Jarman’s Caravaggio, The Last of England, and War Requiem, outdoes herself as a loving spouse who is pushed by her unresponsive husband into becoming the adulterous traitor he imagines her to be. Swinton brings an exquisite range and depth to her character; even in her final scenes, when Isabella has become more of a gorgon than Edward could have imagined (or Marlowe either, seeing as how Jarman has her murdering Kent by biting into his jugular vein!), she retains the queen’s rigid bearing and internalized sense of fear and desperation.

(This review first appeared in The Film Journal, April 1992.)

Link to:

Film: Reviews: Contents

For more on Derek Jarman, see:

Book Review: At Your Own Risk

Film Interview: Derek Jarman

Film Review: Wittgenstein