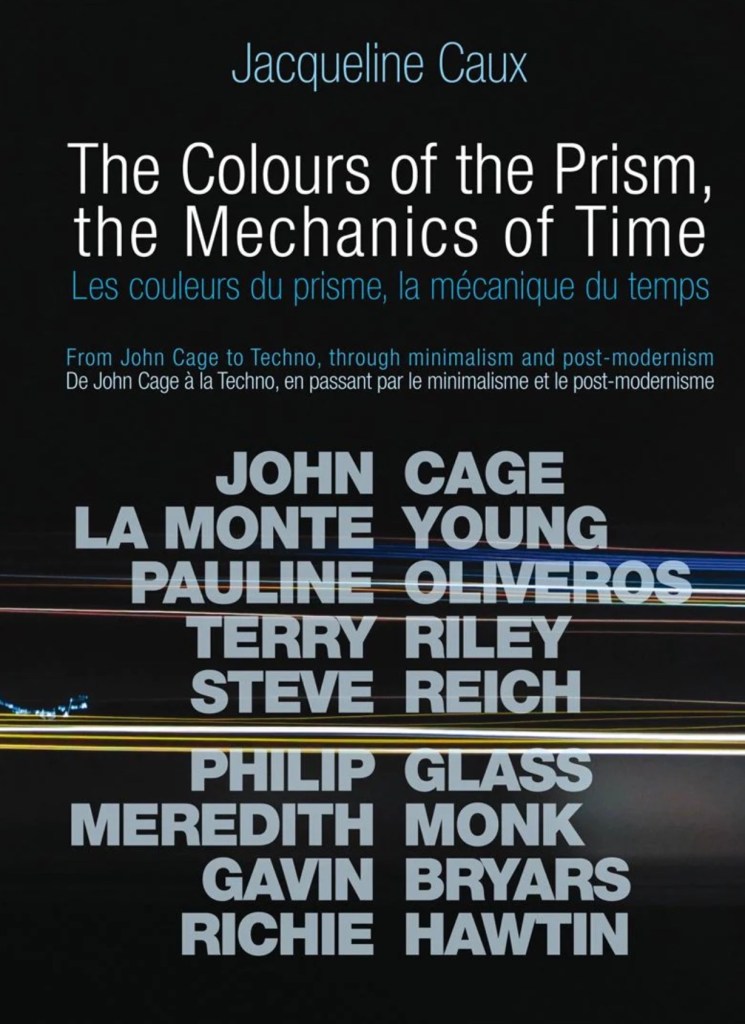

Daniel Caux – musicologist, music critic, and organizer of numerous concerts and events – passed away in 2008, a year before his wife, producer/director Jacqueline Caux, completed her film Les couleurs du prisme, la mécanique du temps. Utilizing his script as well as archival footage and audio of her husband discussing this music, she provides a helpful introduction to the eight composer/musicians who are featured in the film. Pauline Oliveros, La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Meredith Monk, Gavin Bryars, and Richie Hawtin (a.k.a. Plastikman) get about ten minutes apiece to talk about their work and play some of it for the camera. The film’s use of archival commentary by the late John Cage, an essential figure in the development of postmodern music, also provides insights and a greater context for these composers.

Through his innovation of chance and indeterminate composition in the 1950s, Cage wrote scores devoid of intellectual and emotional content, in which any hierarchy of importance among the sounds was strictly avoided. The result was a non-dramatic music that opened the doors for different forms of minimalist composition in the 1960s and ‘70s. The sub-genre of minimalism most successful with audiences has been the use of repeated patterns against a constant pulse, and that approach is the film’s primary focus with sequences on Riley, Reich, Glass, Monk, and Hawtin. Due acknowledgement is made of their major works, with snippets of landmark ensemble music by Riley (In C) and Reich (Music for Eighteen Musicians) and major operas by Glass (Satyagraha) and Monk (Vessel). The welcome inclusion of Young, Oliveros, and Bryars brings greater range to the film’s sound world. There are the dense colors of Young’s masterpiece The Well-Tuned Piano, which he plays on a piano retuned in just intonation (a tuning system that follows the intervals of the overtone series rather than the chromatic scale of equal temperament, which has defined Western music). Oliveros’s Bye Bye Butterfly, a classic of spontaneous electronic music, is excerpted, and she also performs a brief improvisation on accordion (also retuned in just intonation, although the film doesn’t mention it). Bryars is heard speaking in class with his students and playing contrabass in a performance of his Laude Cortonese, a reinvention of Italian madrigal.

Hawtin, an exponent of techno music, may seem out of place in a film devoted to what could be called contemporary classical music, but the Cauxes make a case for techno’s lineage out of pulse-driven repeated-pattern minimalist music. Hawtin, then in his late thirties, is also the youngest composer featured in the film (all the others are in their sixties or seventies), and the film insists that the growth of techno since the late 1980s represents the true “innovation and soul-searching” in contemporary music. Audiences, however, may be hard pressed to hear that depth as they observe Hawtin in performance before an enormous crowd, moving knobs and levers to generate a cold and bloodless electronic dance music that doesn’t move anyone in his sea of listeners to dance.

The inclusion of Hawtin may be a matter of taste, but other aspects of the film are less defensible, starting of course with its pretentious, arbitrary, and forgettable title. Then there’s the perennial problem that confronts all documentarians of music: making a film about something that’s invisible. Caux alas doesn’t always stick to performance footage, and her visuals to accompany music can be hit and miss, with clichés such as subways in New York and trolleys in San Francisco alongside evocative and stylish shots such as the dance of wind-blown newspaper in the street. But these minor flaws won’t stop anyone with a serious interest in music from enjoying this film and learning a good deal more about some of the most important musical figures of our time.

(This review first appeared on filmjournal.com in June of 2011.)

Link to:

Film: Reviews: Contents

For more on these composers, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

More Cool Sites To Visit! – Music

For more on John Cage, see:

Music Book: Sonic Transports – Glenn Branca essay, part 1

Music Book: Sonic Transports – Glenn Branca essay, part 15

Music Essay: The Beaten Path: A History of American Percussion Music

Music Lecture: “Intense Purity of Feeling”: Béla Bartók and American Music

Music Lecture: King of the Omniverse: Sun Ra and His Arkestra

Music Lecture: The Secret of 20th-Century American Music

Music: KALW Radio Show #3, Ancient China in 20th-Century Music

Music: SFCR Radio Show #4, Postmodernism, part 1: Three Founders

Music: SFCR Radio Show #8, Daoism in Western Music, part 1

Music: SFCR Radio Show #19, The Percussion Ensemble

Music: SFCR Radio Show #22, Neo-Classicism, part 3

Music: SFCR Radio Show #25, Schoenberg in America

Music: SFCR Radio Show #29, Electro-Acoustic Music, part 1: New Instruments

For more on John Cage, Philip Glass, and Steve Reich, see:

Music Book: Soundpieces: Interviews with American Composers

For more on Philip Glass, see:

Film Interview: Rudolph Wurlitzer

For more on Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and Terry Riley, see:

Music: SFCR Radio Show #32, Riley, Reich, and Glass

For more on Meredith Monk and Pauline Oliveros, see:

Music: KALW Radio Show #4, Women’s History Month

For more on Pauline Oliveros, see:

Music: KALW Radio Show #6, Gender Variance in Western Music, part 2: Female-to-Male Representations

Music: KALW Radio Show #7, In Tribute

Music: SFCR Radio Show #17, A Tribute to Pauline Oliveros

For more on Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley, and La Monte Young, see:

Music Book: Soundpieces 2: Interviews with American Composers

For more on Pauline Oliveros and La Monte Young, see:

Music Lecture: The Secret of 20th-Century American Music

Music: SFCR Radio Show #5, Minimalism

For more on La Monte Young, see:

Music: SFCR Radio Show #31, A Tribute to La Monte Young