TOUCHING GOD:

SANDY DENNIS’ LIFE AND SPIRITUAL JOURNEY

by Lucinda Riva

copyright © 2023 Lucinda Riva

Lucinda Riva, daughter of beloved character actor Dort Clark, has written an invaluable reminiscence about her close friendship with the great Sandy Dennis. I am honored that she is letting this essay appear here for the first time. Originally conceived as part of a larger manuscript written in the early 2000s, it has been edited into two sections. Part One examines the early days of Sandy Dennis’ career; Part Two details Lucinda Riva’s relationship with this brilliant actor.

PART ONE

In the spring of 1957, after having done two stage productions and many television appearances, Sandy left New York for Florida and the Palm Beach Playhouse production of Bus Stop. Here she met Barbara Baxley, an actress who became a longtime friend and helped catapult Sandy to Broadway.

In a magazine article, Barbara Baxley vividly recalled acting with Sandy in that production: “She showed up and said she had all kinds of experience and had played the part, but one look and I saw she hardly knew stage right from stage left. There she was, fat and beautiful and shy and sensitive, and you could see she had this great talent, but she didn’t know anything. So we kind of nudged her around the stage and pushed her where she was supposed to go, and she caught on. Her part was a long one, but she got her lines bang like that, and she was off. Some of the others said, ‘She’s doing fine in rehearsal, but what about opening night? Maybe she’ll clam up.’ I said, ‘Listen, you don’t ever have to worry about that little lady clamming up. She never will. You just look out for yourself.’ And, of course, I was right. She didn’t.”

Following the run of Bus Stop Sandy returned to New York, where she auditioned and was cast in the title role of The Reluctant Debutante, an English comedy finishing up a successful stint on Broadway, now going out on a summer-stock company tour. With Arthur Treacher and Ruth Chatterton cast as her slightly befuddled high-society parents, the group had a mere five days of rehearsal before opening at the Lakewood Summer Playhouse in Barnesville, Pennsylvania, on June 24, 1957, for five days.

Word of her previous rave notices was beginning to spread and current reviews fed the groundswell. The next stop was Westport, Connecticut, where Sandy would shortly come to live and play many times in ensuing years at the Westport Country Playhouse. In her initial appearance, reviewers raved: “Miss Dennis, a newcomer to the Westport stage, has beauty and talent and shows a finesse and timing a seasoned trouper would envy. As ‘Jane,’ the daughter, she almost steals the show several times as the wholesome teenager, who knows what she wants out of life. She dominates the performance with her charm and skill and excellence.”

Following a stay at the Papermill Playhouse in Millburn, New Jersey, the company played the Hinsdale Theatre in Chicago, and Ann Barzell in the Chicago-American observed: “Miss Dennis turns in a magnificent performance. She is enchanting as the clear-eyed, unaffected kid with the telephone and table manners of the average teenager. She treats her elders with an amused tolerance. Miss Dennis affected a disarmingly untidy appearance that only a beautiful young girl would dare. She is perfectly the part, there is not one false move. One wonders if perhaps Miss Dennis is not acting.” This particular review is interesting in that it seems the first time this observation is being noted and raised, that Sandy is so “perfectly the part… One wonders if Miss Dennis is not acting.”

Miss Dennis was indeed acting, and she was determined to improve her skills upon returning to New York. She enrolled in the Herbert Berghof Studio where she had as acting teachers Berghof, William Hickey, and Lee Grant.

William Inge’s play The Dark at the Top of the Stairs opened on Broadway on December 6, 1957, at the Music Box Theatre. Tuesday Weld, only fifteen years old, had been hired by director Elia “Gadge” Kazan to understudy both ingenue roles of Reenie Flood and Flirt Conroy. Stage Manager Burry Fredrik recalled, “We realized we had to replace Tuesday as the understudy. She simply didn’t have enough life experience or maturity. Barbara Baxley was a very great friend of Bill Inge’s and told Bill about Sandy Dennis. Bill told me and I told Gadge, and we called her in to read. Meanwhile, Gadge himself had a candidate, a young woman working out of the Actors Studio, whom he thought would be good. So we auditioned just the two of them; we didn’t audition anybody else. Gadge said, ‘I’d like to go with my girl,’ and I said, ‘Well, I want to go with Sandy.’ So we had a little set-to, but finally he said, ‘All right, you have to direct them, so it can be Sandy.’

“The thing that fascinated me so about Sandy when she came in to audition was that she was different, that she was original, to say nothing of talented. It was that originality that made me insist that she be with the show.”

In the role of Flirt Conroy – a flapper, a jazzy girl – there is a scene where she does a little barefooted dance. Sandy refused, “I am not going to dance barefoot!”

Burry Fredrik: “And she told me a fib in order not to dance barefoot! She said, ‘I have six toes.’ There we stand, shod, and I guess six toes is possible. Many pussycats have six toes and she probably loved the idea! So I said, ‘Well Sandy, I’ll tell you what’s going to happen. If you don’t dance barefoot, then you will be fired, and I’ll have to find someone who can dance barefoot.’ So those shoes came off, and the dance went in. She repeated this story many times afterward. Very original, she was an absolute original.”

After the play had run in New York for a month, one day Kazan, Bill Inge, and Saint Subber came to see the understudy rehearsal. Sandy had just been cast. As they watched, Kazan turned to the three, “If there was the ‘name value’ here with these understudies to the extent that we will need out on the road, these are the people who should play the national tour.” Burry Fredrik adds, “When we did the national [touring] company, I wouldn’t have anybody else but Sandy play Reenie. Sandy had no arrogance; not at the beginning or the end. Consequently, I had no difficulty with her, other than dancing barefooted! She did what she did so wonderfully well, the best, and with great depth.”

Eileen Heckart played Sandy’s aunt. “I first met Sandy in Dark at the Top of the Stairs; she was the understudy to Judy Robinson. The thing that killed me about her was – she was a very quiet little girl – she carried tomes with her every night to the theatre. Now, none of this was light reading. I remember she had books on the Spanish-American war, Napoleonic history, law books. At that time she was seeing Gerry O’Loughlin. They were very quiet, very discreet, but I couldn’t get over the books. The only frothy books I remember her reading was one mystery writer she liked, P.D. James. Sandy kept saying, ‘Oh she’s just wonderful; you must read her.’

“I’ll never forget when she went on as understudy in Dark at the Top of the Stairs; I think she only went on for two performances when Judy was sick. Boy, she was good! Much better than Judy, and the amazing thing was that that usually never happens with understudies because they don’t have enough chance to work. Boy, she was solid; she was in there!”

After one such performance, Sandy received a handwritten letter dated April 18, 1958, from Stockbridge, Massachusetts. It read: “Dear Sandy, I’m sorry to have missed your performance, but I was up here at the time. However, I have heard very glowing reports of your work. I knew you’d be good. Best wishes, William Inge.”

Notice of Sandy was increasing in the press. In the New York Journal-American on Tuesday, October 28, John McClain titled his column “Light Behind ‘Dark Stairs’” and wrote: “High in the upper reaches of the Music Box Theatre on W. 45th St. where The Dark of the Top of the Stairs has been operating for a year is a cavernous chorus dressing room now occupied by one small doll. This is Sandy Dennis who understudies the young girl roles in the William Inge drama.” He described the nightly checking-in-routine of understudies everywhere and listed the titles of books Sandy had hefted to the theatre to read: Aesthetics and History, Collected Sonnets of Edna St. Vincent Millay, McCullers’ The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, Zola’s Nana, Gide’s The Immoralist.

At the new year, the company prepared to go out on tour with Sandy now in the ingenue role of Reenie. In a letter to her parents, Sandy described her holidays and the upcoming tour:

1/1/59

Dear Mom and Dad,

Just time for a letter before I leave for the theatre. Had a nice “new years eve” I went to a party given by the Strasbrugs Strasburgs (spelling) Everybody famous was there including me, of course, Ha Ha. I drank six glasses of gingerale and practically died of a full bladder because I couldn’t find a john. Today I went to an eggnog party given by Albert Salmi and his wife who is Peggy Ann Garner, so I am full of parties for a while.

I sort of halfway expect my two female roommates and Joe home on Sunday or Monday. I hate staying alone (some of the time) I’ve stayed with Evans a couple of times, but she lets her pet hamster out at nite and I can’t help but put him in the mice and rat family. I mean really she should have cats, don’t you think so Daddy?

Thank you all for the X-mas presents. I loved everything. The chest of drawers cost fifteen dollars so I took the other ten and put $2.50 with it and got the golden pocket-watch on the gold necklace I wanted! So there, everybody should be happy.

Lemo sent me $5.00 which I shall thank her for and I shall certainly write and thank Gram and Adrienne.

We take off in about two weeks. I’m taking my trunk, but have to get the lock fixed first as I broke it in a fit of rage trying to get it open once.

Oh guess what – we are not going to Des Moines, but to Omaha instead. April 9–11 it’s a split week but that’s better than nothing. Do you think maybe you can get over – I mean for a few minutes Ha! Hey I have to go to the bathroom.

I still haven’t got the apt. cleaned up completely yet, hope I can tear into it tomorrow before the others come home, cause it’s always nice to come home to a clean house.

The paint job really looks good. You wouldn’t believe it. Gaby is absolutely devouring food. She (he) sounds like a toilet being flushed.

Well you-all that’s about the extent of my news, so will close now.

Love and kisses

Sandy

In Sandy Dennis: A Personal Memoir Sandy wrote of her experience in The Dark at the Top of the Stairs: “The set was a midwestern house in the 1920s. Stained glass around the front door, blues, yellows, red and a deep purplish color. A huge lamp hung over a round wooden table in the living room of this house. There was a rocking chair and a familiar man’s chair. To the back at the center of the stage were sliding doors that opened to a parlor with a player piano. Everything seemed patterned, dense and full of touchable color. There was a staircase I believed in even though it ended in a wooden platform where we stood to wait for our exits and entrances. When the curtain went up and the lights came on the train of fake leaves hanging behind the stained glass of the door would begin to move, gently blown by a hidden fan. I would stand on that stage watching the scratching of leaves on the glass creating shadows I had seen as a child in those long days that never ended, in a time that exists only in memory, and I would be transfixed, transported into that space we have no name for. In the split of a second I would recover, come hurtling back into reality.

“For over a year I lived in this set. I made friends. I met a man and fell in love and stayed in love for many years and still love in an old way. Then one night the play ended. I would come back to this theatre two more times to play. Three years of my life spent in this theatre on 45th St., where at nineteen years old I had stood in the back of the theatre and watched an actress [Kim Stanley in Bus Stop] who took my breath away. I watched something I had dreamed of, but wasn’t quite sure existed. The last time I left this theatre that lady was my friend.”

Actor/director Martin Fried: “We went to Lee Strasberg’s private classes together. These classes were phenomenal: this was before Brenda or anything. It was like a little ‘star-time’: there was Mike Nichols, Elaine May, Roy Scheider, Geoffrey Horne, Marilyn Monroe used to come, all-star; it was amazing how many people came out of that. Classes were always full of at least 30 people; Strasberg selected you. You had to wait to get in. So he would interview you and if he thought that he would be good for you – he had that privilege then. I went through that interview, so I know the kinds of questions he asked. Sandy would’ve had no problem. He would ask who’s your favorite actor; he wouldn’t get into any Method stuff – he’s a very practical man, Strasberg. And she absolutely adored him. He treated her like anybody else, but he always appreciated talent.”

Jack Lemmon: “I first met Sandy was when I was doing ‘Face of a Hero’ [on Broadway]. I had done it earlier as a ‘Playhouse 90,’ and it was what one might call a ‘successful unsuccess.’ People were very confused by it, and the switchboard lit up like a Christmas tree at CBS. In 1960, we did the play, I think. Bob Joseph, who wrote it and everyone else thought we knew what was wrong, and why people were confused, and where it could be helped very easily and it could make a hell of a play. I said, ‘Well, okay I’ll do it with John Frankenheimer,’ and that was terrific. Except after I’d committed, Frankenheimer couldn’t do it. They ended up getting Alexander MacKendrick, whom I love dearly, but he’d not had that much experience in the theatre. That was the first time I met Sandy. When she read the part in audition, I was blown away. I was blown away right away. It was just absolutely wonderful. There was so much more to that part, after she gave one reading, than I’d realized. And this was a cold reading! She had this one big scene; it was just terrific. She was the best thing in the play, no question of that. Ed Asner was very good in a supporting part; he was very strong.

“Sandy was outstanding. That talent was a light turned on full. Every night. I didn’t get to know her well then, because she wasn’t that gregarious, and I didn’t like to stop her or talk to her too much backstage, because she always seemed to be concentrating. I thought, ‘Well, she’s preparing,’ which I think half the time she was, so I didn’t want to disturb her too much, so I didn’t really feel that I got to know her that well at that point. Then I would see her after the play from time to time, socially or whatever, we’d bump into each other, at Downey’s. Over the years, she’d be very kind and show up at a luncheon being given for me in New York – which was very sweet.”

Porter Van Zandt, the stage manager of A Thousand Clowns: “I was there for all the readings. We read in the lounge out front. Sometimes, often, we’d read onstage, but also out in the lounge. I certainly knew of her and seen her in that one show she’d done before, The Complaisant Lover. She read a number of times, as did a few others. She was up against some other people, there were some good actresses. It was a great role, and she was wonderful in it. She knocked us out at the readings, she impressed everyone there, but we did read her several times. I would read with her. I usually read with everybody. I do remember reading a number of times with Sandy and I thought she was just brilliant. And so she was finally cast. And it was a good cast as you know.

“I enjoyed working with her. I enjoyed her as a person; a lot of people thought she was terribly mannered, and she was, but I never saw Sandy do anything on the stage that was false. I liked her as a person immensely; she had a great sense of humor. She was quite shy: at a time in Clowns, I remember quite well, I did have great respect for her, and I did like her a lot, and I worked with her a lot.

“Sandy was not egotistical. She was extremely shy, but she had a demanding inner integrity that caused her a lot of conflict. In those days, she didn’t know how to handle work situations gracefully. She panicked if she were pushed to betray herself. This business is very difficult for someone like Sandy, with her sensitivity and defenselessness.”

Gene Saks, who co-starred in A Thousand Clowns: “I first met her when she was going with an actor named Gerry O’Loughlin. He was in the Actors Studio with me in the early days. Sandy was in a show [in Boston, 1959] with Myron McCormick, Motel, with Siobhán McKenna. I heard that this young actress was outstanding and talented and that she sort of ran away with that play – which didn’t make it. I believe Gerald was in it, I think that’s where they met. I met her through Gerald.

“The first time we really met was in Clowns. In Clowns her dressing room was right near me, and she had this wonderful relationship with Barry [Gordon]. I didn’t have any big scenes with her except for a moment in the play when she came to the door and I said, ‘Minnie Mouse – he said your name was Minnie Mouse!’

“In Clowns she had the same kind of thing where what she did was – you never knew [as an actor] when she would speak. It used to drive Billy Daniels – who acted with her all the time – he used to go crazy. But you know, there was something about it that he liked. He’s a very serious actor, and he was very aware that it shouldn’t be exactly the same every night. He played with that, he played with her. He sort of loved it, but at the same time it made a nervous wreck of you. It was perfect – the girl was completely unsure of herself. She burned the whole chicken. Sandy was enchanting.

“I thought that Sandy and Jason had been lovers throughout Clowns. Every one of the men that I knew that she was with had a very dark side, very unpredictable, possibly violent side: Gerry O’Loughlin did, he was a dark guy. I liked him a lot, worked with him quite a bit at the Actors Studio. I was married to Bea Arthur at the time, we were both at the Studio, and worked together on projects. She loved Gerry, and so did I. He was always unpredictable, given to dark moods, very much Black Irish.”

George Segal later co-starred with Sandy Dennis in the film of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf: “The moment she was onstage in Clowns, you can see from the force of her personality why Jason would be infatuated with her. She could project that ‘entrancing’ thing off the stage so effortlessly. Sandy always came from a different direction, as did Judy Holliday. They were really smart women who were beyond the bullshit; they couldn’t do that batting-the-eyelashes thing. They were too honest! Sandy was much deeper and much smarter than any of the characters she played.”

Theater director Nicholas Martin was another good friend of Sandy’s: “Sandy did things and said things that had a life! She had a real respect and love for man’s folly – her own, mine, and yours. As well as an enormous reverence for humanity. She would laugh at that description, but she would recognize it. Right next to all the fart jokes, the belching contests, was this extremely elevated, highly moral, individually moral woman who could laugh at herself, first of all. And she never said anything boring!

“The greatest thing she ever said to me was just two words in one of those ‘relationship post-mortem’ discussions, the ‘wisdom that-comes-from-suffering-again’ type. I said, ‘What I want to know is where do we get a chance to use this wisdom that we have achieved through suffering?’

“Sandy said, ‘Oh, I know the answer to that one…’

“‘Well, what is it?’

“‘Somewhere else…’

“I thought that was brilliant. I remember it so distinctly because she was so quick with it; it wasn’t rehearsed or some platitude. It never was with her.

“People constantly talk about how she was contradictory; once she said to me, ‘I cannot read novels; I just don’t read novels.’

“Six months later I saw her with a big stack of novels and said, ‘What are you doing?’

“She said, ‘Well, why wouldn’t I be reading these?’

“‘You said you never read novels!’

“She said, ‘Oh, I never said that!’ And she meant it. She merely went about her business. But there was a certain power in her, in her freedom of expression, that everybody else remembered what she’d said.”

PART TWO

In 1962, my father Dort Clark was doing live television, following his Broadway appearances in South Pacific, Wonderful Town, and Bells Are Ringing with Judy Holliday. I was fifteen years old, growing up in the theatre and adrift in a shifting world, feeling the currents, the unnamed breezes. The Cuban missiles blockade was smoldering to a crisis, and we all mourned Marilyn Monroe’s tragic death. Actors and theatre folks form a tribal community with a shared and generous spirit. “There’s no people like show-people…” painted the colors of my childhood.

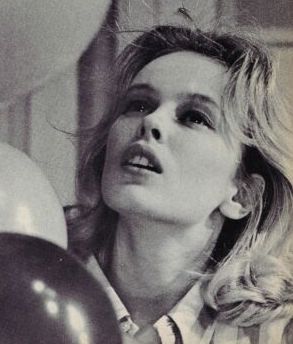

One burnished October afternoon, I attended a matinee of A Thousand Clowns, the comedy hit starring Jason Robards and a newcomer, Sandy Dennis. Although accustomed to watching talented actors, I was struck to stillness seeing Sandy Dennis. As she stood onstage with squared shoulders, splayed feet, and a cloud of curls the color of shiny pale tea framing her mobile mouth, I could feel her breath in my lungs.

After the performance, Jason Robards, a family friend, guided me to Sandy’s dressing room. She leaned against the doorframe as Jason in his gravelly baritone introduced us: “Sandy, I want you to meet Cindy, she’s from an old theatrical family. She’s Dort’s kid. Sandy, Cindy. Cindy, Sandy.”

A shy lightheadedness enveloped me. I dropped my eyes, heard a roaring inner wind, and the solid world cracked open and swirled downward. Sandy dipped her head to glance into my eyes and, looking into her eyes, I was home.

“Come,” she said, her long-fingered, nervously elegant hand enclosing mine, her head inclining sideways, bashful and soft. “Come, eat with me… come…”

She led me across the threshold, and the axis of my life rotated quietly.

One day, she commented that I was her younger self, her little sister, as shy and serious as she had been. Her smiling deep glance assured me that she knew me without questions, without slopping over into my soul. She did not suck the air out of a room. As physical stroking encourages a cat to stretch in openness or a baby to breathe deeply, I stretched and breathed, merging in and out of Sandy in baby steps, learning myself. We joined with the grins of accomplices.

“You’re so sensitive, what a serious funny girl you are,” she said, laughing and shaking her head. Changeable as light striking water, she was more spontaneous and authentic, simply truer than anyone I’d known. Sandy’s unapologetic ease with her own contradictions showed me freedom, as surely as if she’d finger-spelled the word into my hand.

Languid as a lioness, she was earthy and amused with quick eyebrows, but she had a stiletto mind, a spacious spirit. There was nothing ordinary about being in Sandy’s presence; the simplest pursuit – doing the laundry or strolling together with Cookie, her half-collie dog on late-fall days – acquired a glinting sheen.

“Don’t take yourself so seriously” was the ongoing message taught in many ways; Sandy relished keeping me slightly off-balance. Walking down Eighth Avenue, a sudden shove from her shoulder or hip would hurl me off-stride, frequently careening into other people. “Whoa, ha, ha…” she whooped, but her arm yanked me back and kept me from falling. I learned to attune, to anticipate, and my quick sidestep would allow the force of her shove to carry her off-balance, and now both of us laughing uproariously. I’d never let her fall.

Through Sandy’s eyes, I came to see the sacred in the ordinary. We drifted through and devoured books, one a day. In our reading, we touched, stretched and lived in a safer, more gracious world. She set me a reading-list of her favorite authors – Willa Cather, Rebecca West, Rosamond Lehmann, Elizabeth Bowen, James Joyce, and Dostoevsky were discussed in long slow afternoons as Sandy showed me how to fold bed sheets or sort the laundry, darks from lights. How much to fill a washer, which products to add and when, all facets of the laundry became intriguing.

Peggy Cosgrave, Sandy’s best friend, recalled, “No one could do the laundry the way she liked it, and she had to do yours too. She loved to fuss over the products – put Downy in this, do this separately – so you just let her! She needed to be needed that way. It made her feel good, not just to be doing her own things, but to be doing yours, and to see them all laid out.”

Nicholas Martin, another good friend, concurs: “Once I said, ‘Honey, these are not one hundred percent cotton sheets,’ and she said, ‘Oh, if you wash them 10 or 12 times a day, they’ll be fine…’ And she meant it; that washing machine was never off. Never. She loved the laundry. She would go through my bags and take out stuff so she could wash it. It was an expression of love, a goyish version of Jews cooking for you.”

Whether in showing me how to set my hair in “rag-curls” like hers, or pouring over the Ouija board, or walking Cookie in fading golden light, we told each other stories. Sandy loved stories. “Tell me about…” was her invitation and I entertained with tales of my sisters or school; it knocked me out to see her laugh. Her laugh broke into sparkles and spun me in circles, inciting more outlandish stories, just to hear that laugh.

“Now you tell me a story,” I pleaded, following her from room to room as she carried laundry. I pestered her for anecdotes of her Nebraskan childhood, swallowing the details like the bourbon-soaked red cherries, orange slices and green olives filched from her drinks. I became drunk on her stories, giggling at tales such as the time she threw a cast-iron skillet at brother Frankie’s head, or when, in first grade, she recited the alphabet proudly, but backwards from Z to A, and was sent home for impertinence.

Retaining a bloodthirsty imagination, I loved her memory of the hanging body. In Sandy Dennis: A Personal Memoir, she wrote: “I must have been three that summer I saw someone hanging from the basement ceiling. How long did I wait in that empty store, my pennies in my hand? I shifted and counted the tiny Xs that ran across the front of my smocked dress. I walked the length of the counter to the door at the back of the store. It was open and led downstairs to the basement. Halfway down the stairs I saw hanging from the ceiling a person, a grown sexless person. Everything was very still… I turned and walked back up the stairs and stood at the counter in front of the glass jars filled with jaw breakers… I slipped the three pennies from my hand onto the counter, stood on my tiptoes and lifted the tin lid of the slanted glass jar, picked three black jaw breakers and walked out the screen door that closed behind me with a gust of sealed air… That summer I knew it was wrong to take something. It was the first occasion I remember of a moral decision made entirely on my own. The color and heat of that day, the taste of licorice. The sidewalks ribboning home, the empty lot on the corner tall with weeds and hollyhock. The silence of that thousand-year-old endless afternoon. The sexless hanging body remains a mystery. I recognized death, but without compassion or fear.”

One gloomy February afternoon, she and I were settled in her dressing-room awaiting the delivery of dinner. The theatre was hushed in the lull between performances. A protected, timeless sense closed down over us like a glass bell. The room shimmered in overheated silence, sliced only by the hissing of steam-heat and the spitting of sleet against the blackened window. As Sandy rested, I sat on the floor struggling with the plant phylum of biology. Always, Sandy mirrored to me my emerging intelligence; she had reassured me I could master science, promising, “I’ll buy you any puppy you want, yes indeed” for higher grades. The bribe has worked; now I received A’s, and intended to name my puppy Sandy Dennis, or Eli Wallach if a boy. I felt her eyes on me and glanced up.

“Hon, you’ve done so well… but, you know, I can’t really buy you that puppy; it’s just not, mmm, practical. But, uh… I have something special, yes.”

Excited, she rose and tucked obscuring curls behind her ear as she rummaged in her enormous bag on the makeup table. Turning, she thrust out a small velvet box.

Inside the blue box, nestled in dark blue satin, shone an exquisite gold antique pocket-watch on a golden necklace chain. Stunned, I looked into her eyes to see a little diffidence, a soft shyness.

“Ah well, it was mine, you know… I, uh, bought it when I first came to New York. I want you to have it now, my Cindy.” No gift had ever meant so much, and I wore it constantly.

On an icy evening of snapping-blue twilight, as the city’s lights flashed across frigid air, skyscraper to skyscraper, we waited to cross Broadway at Times Square. We were hunched against the roaring traffic and the stinging snow, peering through ice-studded scarves, when Sandy grabbed my shoulders, turning me to face her, and shouted peremptorily (at times, she was so bossy), “Look at me, look me right in the eye!”

Mystified and freezing, I couldn’t do otherwise.

“Your eyes don’t track right,” Sandy yelled above blaring taxi horns, “They’re off-center. When were your eyes were checked last? Huh? And how about the dentist?” We ran through traffic and into a bakery to buy dinner: a huge fudge-frosted chocolate cake. Then I bought our tickets for Breakfast at Tiffany’s and Sandy smuggled the cake into the movie-theatre. We hunkered down in the front seats, devouring the cake with our fingers and bawling over Audrey Hepburn hugging her soaked orange-tabby cat to her skinny chest in the drenching rain.

“Tomorrow, we upgrade your health,” Sandy announced, wiping still-wet eyes with her wetter scarf as strains of “Moon River” followed us up the aisle. We sprinted through snowbanks back to the Eugene O’Neill Theatre for her evening performance.

A whirlwind of dentist and doctors’ appointments resulted in new medication for asthma and brand-new contact lenses. Being freed of thick glasses, or from having to myopically braille my way through life, brought me closer to a more beautiful, grown-up world.

Some evenings, we’d join her crowd at Downey’s. The restaurant was a theatrical hang-out, a refuge for dedicated young actors, writers, directors, for the stars and the starving. Jim Downey, florid owner and Irish uncle to all, would urge “Eat, eat… when you get famous, you’ll pay me!” Downey’s was a second home; my father’s photograph hung among the actors’ 8×10 glossies above the bar.

Often appropriating the round front booth were Brenda Vaccaro, Mark Rydell, Geraldine Page, Rip Torn, and other Actors Studio members; we’d squash together making more room as newcomers arrived. Shy, I’d slowly fade, quietly meeting no eyes. Sandy would order two vermouth cassises and shoot me conspiratorial winks. The adults talked, and her hand would glide one vermouth cassis to me as I leaned against her.

Brenda Vaccaro, her voice loose, deep, and amused, sometimes joined us when we poked through dusty antique stores on the Upper West Side. “Sandy and I had met at an Actors Studio Benefit. Sandy was in A Thousand Clowns; I was in The Affair. I wore a grey long skirt and a grey V-neck sweater, a pullover, and she saw me all in grey with my brown hair and said, ‘That girl’s going to be my friend.’” After picking up groceries at the corner market, we’d return home where I’d “research adulthood” in observing Sandy and Brenda discussing their boyfriends, trading incomprehensible private jokes, soon howling with laughter. The humor eluded me, but I soaked in their contagious slyness, and then we’d all be honking and snorting, rolling on the floor peeing in our pants until Sandy would suddenly remember, “Oh heavens, honey, Cookie needs a walk. Would you, uh, be so kind as to take her out, you know, on a little walk?” Sandy, the guardian of my innocence.

In another attempt to safeguard my morals, Sandy had told me that she and boyfriend Gerry O’Loughlin were married. One day, while arranging a bowl of early yellow tulips, I idly asked, “Why don’t you wear a wedding-ring?”

She flashed angrily, the narrow pink end of her tongue lizardly darting, “Nobody has the right to make me wear anything I don’t want to! It’s entirely up to me.” I observed these fireworks with a calm and particular interest; this display of temper was yet another Sandy.

In childhood, we had each endured flamboyant, histrionic mothers who courted being the focus of all attention, possessing no sense of personal boundaries. Consequently, Sandy and I shared a horror of intrusion, and were utterly repelled by the self-indulgence of emotional excess. We had a tacit understanding.

Sandy’s niece Michelle Dennis later told me, “Before Sandy died, she told me that she felt Yvonne [Sandy’s mother] had molested her as a kid. Sandy said, ‘A child is the one thing you can’t distance; if someone were to ridicule or hurt her, I couldn’t bear it.’

“Sandy wouldn’t know how to deal with any pain or conflict the child would encounter. There was a part of Sandy that was so empathetic that it was almost too scary. She could not deal with any living creature being hurt. Yvonne was terrible to Sandy, divisive and mean to Sandy’s friends. Yvonne was bigger than life, wild, flamboyant, demeaning, and promiscuous. She wanted to be the star.”

***

In early April, Sandy filmed another “Naked City.” Some scenes of the episode, “Carrier,” were shot on location at the Children’s Zoo in Central Park. I watched for a while, then wandered away.

The park felt cool and empty; city dogs ran in circles around the trees. I trailed them aimlessly. Change pressed in on my chest. Gasping against the wind for a breath, I forced myself to think about leaving New York, my family’s upcoming move to the coast, and about Sandy’s sadness at leaving A Thousand Clowns.

“It’s time to move on,” Sandy’s agent had advised. “Take the new contract with Warner Bros.-Seven Arts; you can’t pass that up!”

Within me, Sandy’s voice, “No crying, don’t let them know, no crying at all.”

***

“Cookie, come on, let’s go home… down, girl,” she ordered as Cookie wiped muddy paws on her tan trench coat. They hurried across West End Avenue; she must return her manager’s phone call and change before class. Pulling a sweater-tunic over her black turtleneck and skirt, she thrust her feet into loafers. Then, wrestling with her enormous book-filled bag, she nearly strangled herself by slamming her long scarf in the door.

In Lee Strasberg’s private class, Sandy took a seat, looking for Brenda Vaccaro. Visiting the class was a member of the Playwriting Unit of the Actors Studio, Muriel Resnik, who had finished her first script, Any Wednesday. Sandy Dennis had been mentioned to her as a possibility for the female lead, but Resnik preferred Barbara Harris or Zohra Lampert. Resnik knew that Sandy had won a Tony Award for her performance in Clowns, but she hadn’t seen the play and only vaguely remembered Sandy as a fat English teenager from the prior season’s The Complaisant Lover.

“I watched with enormous interest,” Resnik recounted. “She wasn’t thin but she wasn’t a fat English teenager either, and contrary to my memory of her, she was pretty. I went right home and called the boys [producers George W. George and Frank Granat], told them I’d been wrong, and now wanted Sandy Dennis for the role. She’d be very good as Ellen but must lose weight.”

Leaving the Studio in the late afternoon, Sandy walked the few blocks to Downey’s, dropped into a booth, and greeted the newspaper columnist waiting there for a brief interview. Over ground sirloin smothered in onions, Sandy discussed her upcoming contract with Warner Bros.-Seven Arts: “$15,000 per film for seven films. My agent said to grab it, but I don’t know. All I want to do is act. So what do I do? I get involved with lawyers and contracts and money, and that’s not what acting is about. I’m looking to buy a house in the country, in Connecticut, around Wilton or Weston. I love to stay home, and the animals need more space. I’m a simple person; I close my eyes and dream of things I’ve seen on PBS.”

Her eyes shuttered momentarily; she drifted within, observing: “My house will be filled with roses full blown. Nothing, no one will eat these soft fragrant petals and leaves. My table will be laden with vegetables. Friends will come and we will toss salads and dry herbs and always the gardener, like the reserved yet feeling butler in English novels, will watch with affection and humor. I will lovingly arrange fragrant multicolored flowers in vases on polished tables. Perhaps in this vision I will be photographed stretched languidly on a great down blue-and-white patterned sofa with books, one golden retriever at my feet and a matching orange cat.”

***

The following Saturday, April 27th, was Sandy’s 26th birthday; the day spread ahead like honey in the sun. In the park, daffodils and forsythia were yellow dots against the new grey-green lace of spring; we bent our heads together into the scudding breeze and planned the dinner.

I’d composed a birthday poem. For weeks I’d secretly, furtively persevered in iambic pentameter and rhyming schemes, in swirling calligraphy, lettering the verse in black India ink against a watercolor-wash, blues, pale yellows, pinks. Now I unearthed it from beneath a mountain-in-the-closet of one hundred rolls of toilet-paper, a quantity-buy of which Sandy had been so proud. Showing off her bargain to Brenda, she’d crowed, “I thought Gerry was gonna shit!”

Brenda, quick with a comeback, “Well, isn’t that what you want him to do?”

I rolled the poem into a scroll, tied it in her favorite blue ribbons, and nervously placed it by her plate. For Sandy, who loved to give presents, being a recipient could glaze her eyes with oceanic remoteness. Vulnerability or extravagance was too embarrassing. Backstage, I’d observed her graceful acceptance of a fan’s effusive attention; only later, she’d roll her eyes at the emotional display. She hated it.

Gerry and I studied her as she opened and read the poem while lacing the satin ribbons through her slim fingers. I dropped my hot face into my hands, then looked up, stammering, but she silenced me with an upraised index finger and arched brows. Her hand fluttered to her throat, her eyes glistened. I wondered if she was acting. With a tiny shake of her head, she rose, passing behind me to center the poem on the mantelpiece. Then, her hands came down lightly on my hair and arms encircled my neck.

“It’s wonderful, incredible!” and she kissed my hair and we were all gently relieved, a soft tension lightened by a spasm of my surprised disgust at tasting her capers on veal, “Yechhh!” Laughing, Sandy and Gerry spewed peas and potatoes.

That night, lingering and quiet, she sat on my bed.

“When I was your age, I didn’t want to live with my mother, either, ah, I wanted my Aunt Adrienne, who I loved more than anyone. But they sent me to live with Aunt Lemo in Elmira, New York. She and Uncle Ced… they never spoke to each other. Can you believe she taught marriage, family, love courses? Ahh, it was just horrible, the most repressive, ‘You have to do this, you have to do that.’ I hated the whole summer. I’ll never forget it. A better summer was when we went to Colorado, and I saw The Time of the Cuckoo with Shirley Booth. I scooted down front, sitting on the steps as close to the stage as I could. Mmm, I sent Miss Booth my very own St. Christopher’s medal with a note, a poem I wrote.” She looked at me. “I was just your age.”

Smoothing the white quilt, she considered me a long soft while, “Ohhh, you, too… you’re a serious, funny girl.”

***

California, 1963. Like an ebbing tide, New York actors had begun traveling “out to the coast” to find work, staying at the Beverly Hills hotels, the Chateau Marmont above the Sunset Strip, or the Montecito Hotel above Hollywood Boulevard.

As Sandy entered the dim and cool lobby of the Montecito, she saw her name among others in small white letters upon the black “NEW YORK GUESTS” felt board, standing near the entrance. This board was a favorite meeting spot in the hotel; all the emigres enjoyed discovering who else from New York was registered. Here in the lobby, in the lounge and by the pool, contacts were cultivated, friendships forged, and on-the-road stories swapped.

Sandy surveyed her sixth-floor room. It was small, containing a pull-down wall-bed, a tiny kitchenette, and tinier bath, altogether dismal and crowded with the scratchy-plush furniture. She leaned on the peeling paint of the metal windowsill and stared into mid-distance. Lining Hollywood Blvd. were desiccated palm trees like pineapples on steroids, which flapped their fanning leaves. The smoggy air leached colors from all it touched: the sky, the leaves, the pavement, all were overlain with a grey wash. Any remaining color was boiled into blanket-whiteness by a blinding sun. Where was the softness, the grey-green of an afternoon rain shower? This desert land with its assaultive light confused her.

But Brenda Vaccaro was also here filming television episodes; they’d meet for dinner later.

***

In the spring of 1963, my father had been forced by economics to make the difficult decision to move our family to California. Fewer Broadway shows were being produced; audience numbers had declined; there had been a damaging newspaper strike as well as one by Actors’ Equity. My father faced the colossal gamble of selling our three-story home in Summit, New Jersey, and uprooting us to the coast.

A thick paint of grey anger and desolation covered me when I thought of leaving New York; nothing penetrated. My one lifeline was Sandy. On arrival in California I was to live with her at the Montecito. On the phone, Sandy tried to reassure us both, “It’ll be fine, really, Brenda’s here… We can go to bookstores, and, mmmm watch old movies late on TV, and eat coffee ice cream.” We excelled at those pursuits.

And so we bravely attempted. There were no bookstores within walking distance of the hotel; neither Sandy nor I could drive. We walked down Cherokee Avenue to Hollywood Blvd. for dinner at Musso & Frank Grill. My lungs raggedly seized in the smog; I could barely keep a breath. The hot dry air felt grisly, particulate, a red-grey element that one tangibly walked through, as if piles of burning tires encircled the city.

One morning we woke at a primordial hour; she had an early call at Universal Studios. We drank instant coffee in bed, then I watched as Sandy brushed out her rag-curls and applied her moisture cream, Antoine’s, the scent of security to me in these months.

“Brenda’s driving you…?”

“Mmm yes, yes… she’ll be here any minute. Fittings will be all morning, then we’re meeting Mark Rydell for lunch. What’ll you do?”

“I want to finish my book, then go to the pool, I think.”

Brenda arrived in a flurry; together, they left in a whirlwind. I slipped into a quiet morning of sunlit reading.

The door slammed open, too soon to be Sandy, I thought, as Sandy exploded into the room, incensed, scowling, a stalking cloud of anger. Brenda followed, exclaiming in her smokey voice, hands waving like herons. With eyes narrowed, Sandy paced, smoking like a fiend, upraised index-finger jabbing the air emphatically and shouting, “I will act big boobs, not wear them… They can’t make me, those sons of bitches!”

Uncomprehending, I looked to Brenda for a translation.

Brenda said, “She flipped out! I dropped her off at the studio and left. She went to Costume, and she flipped out! She called me to come back to Universal and pick her up. They wanted her to wear a girdle, and she flipped out! She walked off the show! She’s crazy! I said, ‘Sandy, honey, if that was me, I’d’ve worn two girdles!’”

Sandy, still pacing and yelling: “I felt like a freak, you know, not enough bosom and too many teeth, that’s the feeling they give you! They started stuffing falsies down my blouse, telling me to get my teeth filed down and capped. Capped! After seven years of orthodontia, I still smile with my hand over my mouth!”

***

Before the summer ended, Sandy did complete one TV show, “The Fugitive” for Quinn-Martin; production went smoothly. The star, David Janssen, adored working with her in an episode called “The Other Side of the Mountain.” She played an enterprising backwoods girl dressed in loose blue jeans and a large shirt – no falsies, no girdle.

My heart shattered into a million weeping pieces. The day loomed when Sandy would leave, and I missed her in advance, even as we’d sit talking. Squirreling away images like acorns against a barren winter, I’d memorize her abrupt, haphazard movement, her breezy voice, her wry stubborn ways. My eyelids stung with unshed tears.

One night, Sandy was out with friends. Vibrating, I swallowed pills, and dragged the tip of a fingernail scissors across the thin skin of my wrist. My skin was pale, not bronzed like the blonde surfer-bunnies who giggled on beaches at beefy teenaged lifeguards. I watched pointillistic red beads ooze like tiny pomegranate seeds. I crept into a corner beneath the desk in the dark.

The clatter of a door key, the darkened room moved, then Sandy’s face over me faded in and out of a fuzzy mist. Her hands cupped my chin, shook my head sharply, “Hey… hey… hey…” Hands passed roughly over my eyes, moving wet hair. The light spilling from the bathroom was blocked by her face coming close, gazing deeply. “Oh jeez…” Her face disappeared, then her hands lifted my head, a wet cloth wiped my face and crusty wrist. A bandage, a blanket, sips of water and silence until Sandy collapsed onto the couch, struck a match, and demanded crisply, “All right then, what is this? Tell me!”

Not relishing this role, she swiftly smoked about 47,000 Parliaments, the tips of orange glow-light pulsing as she pulled. Her chin tilted upward, as she blew feathers of smoke into shadows, and I sobbed aloud the tears that had been waiting on the edge. She hated crying but I couldn’t be a grown-up now, too alone to live. The terror sat crushing my chest, no air, sobbing and frantic, pulling for air, wheezing, no air, frantic, gasping blackness, terror… Surprising me in softness, Sandy was beside me. She led me to the bathroom and folded me over the sink of steaming water under a draped towel tent. Her hand stroked my back in a slow sweep, “Blow out, in, slow, blow it out… match my breath, Cindy honey, come on, breathe with me.” I leaned against her solid love.

We breathed the same breaths as her circling touch drained the terror and she murmured I would live.

“But I ha-ate it here, these deplorable idiots…”

“No, no, no, now, you’re just loving what you’ve known, but you know that. It’s just the ache of something new, not forever, no. Ahh, come on, you’re my serious funny girl… We’ll always be friends. We’ll write and talk on the phone and visit, you’ll come back to New York.”

Her words, her voice, had the power of incantation.

“Come, come,” she said, pulling down the wall-bed in the dark. Alongside her, I curled in like a blind baby hamster, breathing raggedy breaths to her calm cadence, hiccupping residual tears.

“Shh, don’t cry… shh, baby… you’ll make me feel bad.”

I wailed, “Okay-y-y…”

Being with Sandy was the least lonely I’d ever been.

Link to:

Film: Essays: Contents