Anne LeBaron, Hyperopera, and Crescent City: Some Historical Perspectives

Four decades ago Anne LeBaron first won audiences with Concerto for Active Frogs (1975), a theatrical and amusing work for voices, winds, percussion, and tape, and today that piece can be regarded as something of an overture to her career as a composer. It offers a deft and memorable statement of themes to come: concert theater, improvisation, and electronic sound, all infused with humor, ritual, and environmentalism. Throughout the ensuing years she has embraced a wide spectrum of media and styles, producing memorable scores of every stripe, from orchestra to mixed chamber groups to soloist, with and without electronics, as well as vocal works ranging from art songs and choral scores to music theater and opera. She has blended East and West in multi-cultural compositions such as Lamentation/Invocation (1984) for baritone and three instruments, with its Korean-inspired gestures and haunting long sustained tones for the voice, and her large-scale celebration of Kazakhstan, The Silent Steppe Cantata (2011). Her music can be rich in Americana, as in her blues-inflected opera The E & O Line (1993), the lively American Icons (1996) for orchestra, and Traces of Mississippi (2000) for chorus, orchestra, poet narrators, and rap artists – and, for that matter, her evocation of Edgar Allan Poe, Devil in the Belfry (1993) for violin and piano, as well as her setting of Gertrude Stein, Is Money Money (2000). LeBaron’s inclinations toward theater are another fundamental, from the harp solos I Am an American … My Government Will Reward You (1988) and Hsing (2002) to her dramatic works for soprano and chamber musicians: Pope Joan (2000), Transfiguration (2003), and Sucktion (2008), or the full-scale operas Croak (The Last Frog) (1996) and Wet (2005).

An essential factor of LeBaron’s composition is her musicianship. A gifted harpist, she utilizes electro-acoustic set-ups and extended performance techniques, many of which she has invented and disseminated. LeBaron is also a superb improviser and has honed her skills playing with an array of creative composer/musicians, including Anthony Braxton, Muhal Richard Abrams, Evan Parker, George Lewis, Derek Bailey, Leroy Jenkins, Lionel Hampton, Shelley Hirsch, Davey Williams, and LaDonna Smith. Her ability to put together changing sounds in real time also characterizes her composition, where she likewise demonstrates a sensitive ear for how different sounds relate. This talent for bringing together elements of numerous musical genres and cultures, as in her recent Breathtails (2011) for voice, string quartet, and shakuhachi,springs from LeBaron’s recognition of the relationships – compositional, gestural, spiritual – through which seemingly disparate things connect and support each other.

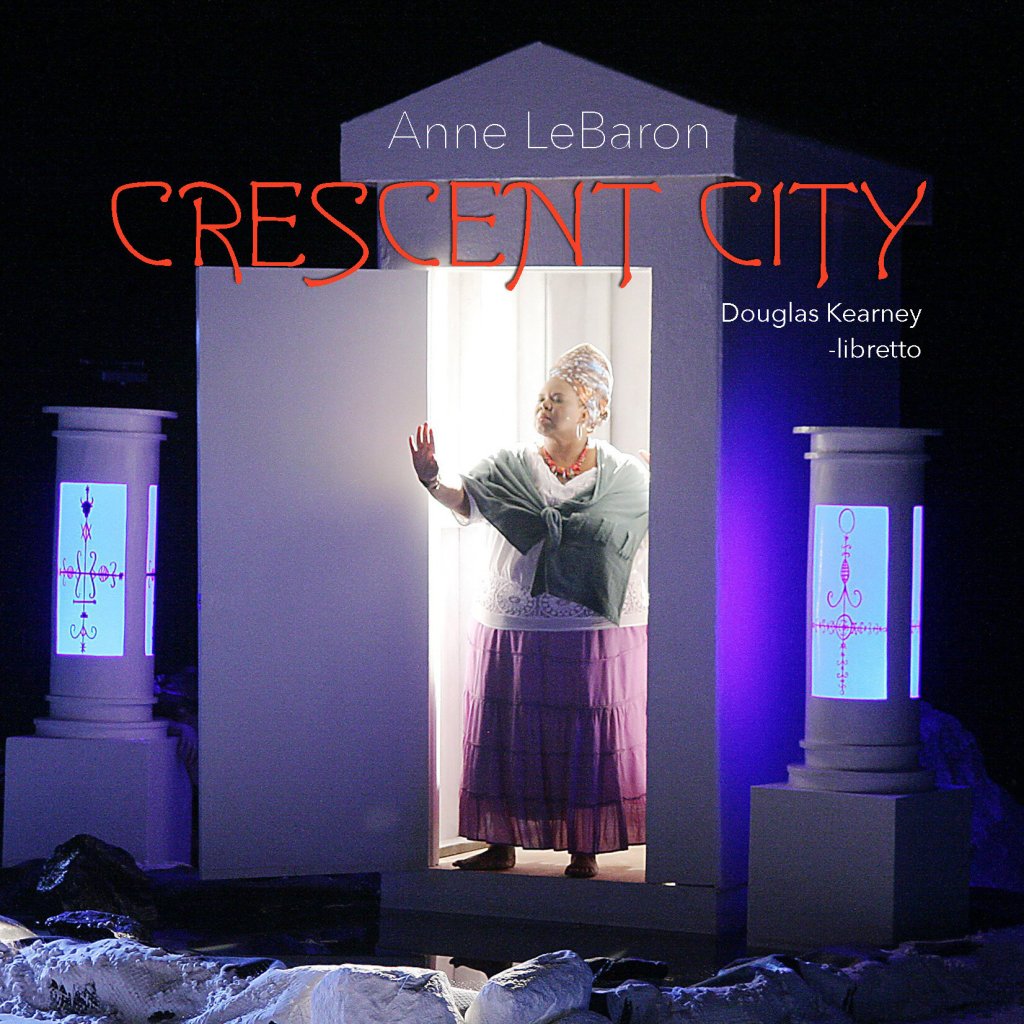

Her gift for creating dynamic connections was raised to a new level of expression with the 2012 premiere of Crescent City, which embodies LeBaron’s concept of hyperopera, defined in her notes for the program: “an opera resulting from intensive collaboration across all the disciplines essential for producing opera in the 21st century – in a word, a ‘meta-collaborative’ undertaking. Collaborative relationships, which are normally, in opera, cemented in established top-down hierarchies, are reassessed, encouraging a more holistic process of artistic collaboration among composer, librettist, director, designers, musicians, and vocalists.” Hyperopera might seem to have roots reaching back to Richard Wagner’s vision of the Gesamtkunstwerk (the united/total/universal artwork that would synthesize architecture, scenic painting, singing, instrumental music, poetry, drama, and dance). However, LeBaron’s concept of hyperopera goes further by breaking down the usual hierarchical structures that define the roles of individuals on creative and production teams, and shifting these into a more lateral and inclusive collaborative engagement.

For most of the 20th century, the cost and logistics of opera production made the genre increasingly inflexible, and no modernist opera composer became the kind of game-changer Wagner had been. It was the postmodern avant-garde – notably Robert Ashley, Meredith Monk, and Robert Wilson – who transformed opera in the 1960s and ‘70s. In his epochal video opera for television Perfect Lives (1977-1980) and the major works that followed, Ashley used small groups of players to create a non-dramatic multimedia form of music theater, centered in improvisation and rooted in electronic sound, blending pop, jazz, rock, atonality, and noise.

With Robert Ashley’s death in 2014, the question of new directions in 21st-century opera has become more acute – and Anne LeBaron’s development of hyperopera is even more urgent. Like Wagner and Ashley, she sees in opera the perfect nexus for the arts, and her hyperopera Crescent City (2012), with a libretto by Douglas Kearney, can be regarded as a bridge between those masters of 19th- and 20th-century opera. LeBaron, like Wagner, relies on the voices of the operatic tradition; but as in Ashley’s operas, you’re just as liable to hear those voices in pop, blues, jazz, rock, or experimental stylings. She abandons the Wagnerian orchestra and, like Ashley, combines her singers with smaller and more specialized forces of instruments and electronic sound, which also move readily among stylistic genres; unlike Ashley, the instrumental and vocal parts are, for the most part, as faithfully notated as the score of Parsifal. LeBaron also differs from Ashley in that she is not a minimalist. Her music at certain privileged moments can become completely still or hushed with simplicity or lost to the world, but she has not walked away from contrast, drama, and story. Like Wagner, she aspires to create a repeatable theatrical drama that will rivet an audience; but like Ashley, she fragments her opera through a prism of video work and performance freedoms and simultaneities.

Also like Ashley (and unlike Wagner), LeBaron believes in collaboration. For Ashley, collaboration took place among the immediate musicmakers: himself and the other vocalists, along with the instrumentalists and sound designers. But while LeBaron suitably tailored parts to her players – she could write Marie Laveau’s part so startlingly low only for a contralto of Gwendolyn Brown’s range! – the collaborations in Crescent City’s realization occurred on an even deeper level. The world premiere production, conceived and directed by Yuval Sharon, engaged six visual artists to participate in the collaborative process by designing and building installation set pieces as the various locales of the opera’s action. Lighting, video, and sound designers also worked together in the development of Crescent City.

Hyperopera can also claim inspiration from Harry Partch, a composer especially relevant to Anne LeBaron and Crescent City. When Deadly Belle headlines at The Chit Hole, her wheezy and woozy accompaniment is a chromelodeon: a harmonium retuned to Partch’s system of 43 tones to the octave. LeBaron has also written for Partch instruments in her 1994 chamber piece Southern Ephemera and plans to include them in her next hyperopera, Psyche & Delia, an investigation of LSD.

Harry Partch took the Gesamtkunstwerk idea so seriously that he built his own instruments as objects of sculptural beauty, tuned them to his own just-intonation system, and featured them onstage in his music theater works. They were played by costumed musicians who not only interacted with singers, actors, and dancers, but also were charged with singing, acting, and dancing. But woe to those who call what Partch did any kind of “opera.” As Partch explained in his notes for the premiere of Water! Water! (1961), “Singing is always involved in these works, recitatives and choruses frequently, yet they are never opera.”

An apocalyptic satire that features a Deluge, Partch’s Water! Water! – although not an opera – serves as a kind of missing link between Kurt Weill’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny and Anne LeBaron’s Crescent City. The same can also be said of a few other not-operas of roughly the same time. Manuel de Falla’s scenic cantata Atlántida (completed posthumously by Ernesto Halffter in 1961 and revised in 1976) includes the submergence of Atlantis; the Biblical story of Noah and the Flood is retold by Benjamin Britten in Noye’s Fludde (1957) and by Igor Stravinsky in his “musical play” for television, The Flood (1962). Of course, the rogues gallery that populates Bertolt Brecht’s city of Mahagonny as it rises and falls makes it an essential precursor for Crescent City. The fundamental vision of LeBaron’s hyperopera, however, is not the political analysis of Brecht and Weill but rather the common concern of Partch and Falla and Britten and Stravinsky: our fatal, catastrophic disconnect from the undying spiritual forces that surround us. People have settled for what they can buy and sell, what they can eat and fuck, and none of that helps when the waters start rising.

Throughout Water! Water! Partch wove his own English rendition of the first two lines of Chapter 8 of the Dao De Jing: “The highest goodness is like water. It seeks the low place that all men dislike.” Water does indeed seek the lowest point, and no place is lower or more detestable than the shambles that is Crescent City. Which means that the oncoming flood must be a good thing. (The imminent hurricane does already have the name Charity.)

Responding to Marie Laveau’s plea, the jaded Loa (gods and goddesses from the Vodou pantheon) deign to manifest themselves, prowling the streets of Crescent City like angels in Sodom as they search for good people to justify sparing the city from disaster. But the only people who attract the Loa and become their ‘vessels’ are social misfits: a pair of cokehead nurses, a drag chanteuse, men who kill. (These characters become possessed by their archetypal Loa, so that each singer takes on two roles.) Marie Laveau, like an improvising composer who is expert at putting different things together, truly understands the old maxim, as above so below. In Scene 6 she declares, “All my power don’t come from Loa. Some of it comes from lower,” and makes a suggestive movement. These two power sources – as well as an appetite for poetry and pun, gods and lowlifes – make themselves available to you when you have one foot in dirt and one foot in water and are home on land and in the river. And when you have all that, so what if your name is mud?

(This essay first appeared in the liner notes of the Innova 878 CD release of Crescent City, October 2014.)

Link to:

Music: Essays: Contents

For more on these composers, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

More Cool Sites To Visit! – Music

For more on Robert Ashley, see:

Music Book: SONIC TRANSPORTS: “Blue” Gene Tyranny Essay, part 6

Music Book: Soundpieces: Interviews with American Composers

Music Essay: You Can Always Go Downtown

Music Lecture: My Experiences of Surrealism in 20th-Century American Music

Music: SFCR Radio Show #5, Postmodernism, part 2: Minimalism

Music: SFCR Radio Show #12, A Tribute to Robert Ashley

Music: SFCR Radio Show #35, Electro-Acoustic Music, part 3: Musicians and Synthesized Sound

For more on Anne LeBaron, see:

Music Book: Soundpieces 2: Interviews with American Composers

Music: KALW Radio Show #1, A Few of My Favorite Things…

Music: KALW Radio Show #4, Women’s History Month

Music: KALW Radio Show #5, Gender Variance in Western Music, part 1: Male-to-Female Representations

Music: KALW Radio Show #6, Gender Variance in Western Music, part 2: Female-to-Male Representations

Music: SFCR Radio Show #6, Postmodernism, part 3: Three Contemporary Masters

For more on Harry Partch, see:

Music Essay: The Beaten Path: A History of American Percussion Music

Music Essay: The Built Environment in American Music

Music: SFCR Radio Show #4, Postmodernism, part 1: Three Founders

Music: SFCR Radio Show #8, Daoism and Western Music, part 1