Conlon Nancarrow

Few musical instruments are as malleable and adaptable as the piano. Its timbres can be altered; its strings adjusted to sound a variety of tunings; its interior played with a subtlety and range rivaling that of its keyboard. While these possibilities continue to be explored and developed by composers throughout the world, an ever-growing number of composers, musicians, and music lovers are paradoxically becoming devoted to music written for the piano’s lowliest, most neglected incarnation: the player piano. The magical music of Conlon Nancarrow has won them over.

Since the late 1940s, Nancarrow has labored in the peace and solitude of his Mexico City studio, creating his amazing Studies for Player Piano. This music seems to belong more to the world of our dreams than to everyday reality. Glissandi and arpeggios shoot past at lightning-fast velocities, seeming to fuse into the sounds of an unearthly gong. Trills tear at you like machine-gun fire. Musical lines spin out and pile up, as the lone player piano splits and divides into an array of pianos, resurrecting the best monster-concert tradition of Gottschalk.

Equally astonishing is the vast expressive range of the Studies. The music can be haunting and delicate or blisteringly intense. Some Studies are witty and lighthearted; others are severe, almost forbidding – cyclones of unprecedented sonic force.

Conlon Nancarrow was born on October 27, 1912, in Texarkana, Arkansas. “We had a player piano in the house when I was a child,” he said, “and I was fascinated by this thing that would play all of these fantastic things by itself. And so from then on I had this way in the back of my mind.”

His early musical development was typically American. His studies included Western concert music counterbalanced with time spent performing popular music. Interestingly, Nancarrow played jazz trumpet for many years, but he has never played the piano.

In the mid-1930s his composition studies were perfunctory, and by 1938 he was off to Spain, fighting fascism as a member of the Lincoln Brigade. He resumed composing when he returned to the United States in 1939. It was at this time that Nancarrow read Henry Cowell’s New Musical Resources, which suggested using the player piano to perform difficult rhythms. For Nancarrow the book was “a big push ahead.”

Unfortunately, this was also a period of mounting frustration, both artistic and personal. Performances of his music were infrequent and inept, as musicians floundered in the rhythmic complexities of his scores. Moreover, Nancarrow felt profoundly disillusioned with American politics, so he immigrated to Mexico, arriving there late in 1940. By the end of the decade, he had abandoned composition for traditional instruments and turned all his attention to composing for the player piano.

Nancarrow’s early Studies, like the instrumental works that preceded them, display a fondness for jazz and blues. This quality is especially pronounced in works like No. 3, the extraordinary “Boogie-Woogie Suite,” and No. 12, with its amazing evocations of flamenco guitars. With these Studies, it is not only our image of the piano disintegrates; the musical genres themselves seem to explode and reshape right before our ears.

As Nancarrow became more familiar with the capabilities of the player piano, however, his music became increasingly less referential, and it is the later Studies that most clearly exemplify his all-consuming interest in tempo. Sometimes his investigations are quite straightforward. Study No. 21 consists of two simultaneous lines: One starts quickly, at about 37 notes per second, and continuously decelerates, while the other begins slowly and continuously accelerates, finishing at an astonishing 111 notes per second. Other Studies venture into even more unusual territories.

The majority of these pieces involve canonic procedures. Nancarrow jokingly describes this device as a compositional shortcut: When writing in this way, he has to compose only one melody! Of course, the real value of canon is that it permits listeners to follow the temporal relationships more easily. When you’re trying to track, say, 21/24/25, you need all the help you can get! This question of the limits of perception pinpoints the importance of Nancarrow’s music. His Studies are redefining our ability to hear.

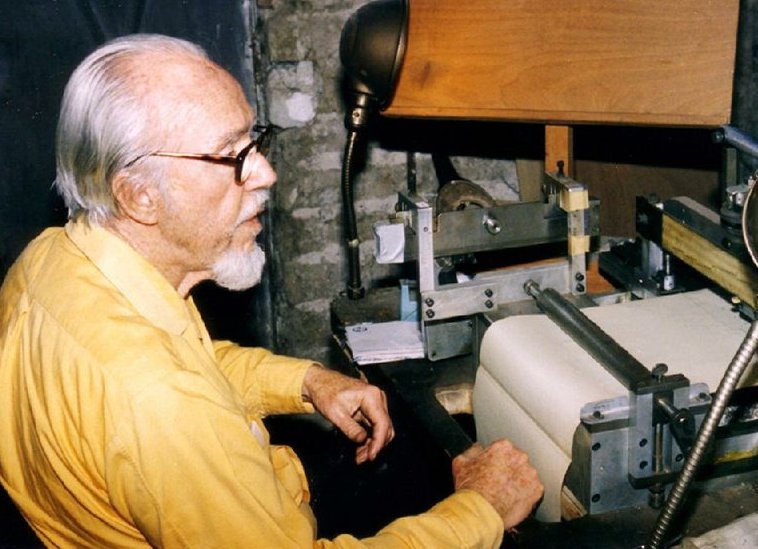

When Nancarrow composes, he begins with only a rough score; the piece is edited and finalized as he punches it out. Punching a roll is a lengthy, painstaking process, taking months to complete. Originally, Nancarrow worked with a machine that advanced by tiny, fixed increments, which limited how precisely he could control duration and attack. Eventually he modified the machine in such a way that he could punch a hole at any point on the piano roll, thus enabling him to create the gradual and subtle changes of tempo which are the glory of his Studies.

After having been ignored for many years, Nancarrow has begun to receive various grants, commissions, and awards. The American Music Center has given him its Letter of Distinction. The MacArthur Foundation recently awarded him a substantial sum of money with which to carry on his work. Nancarrow is a private, rather shy man, and much of this recognition is due to the efforts of a younger generation that has recognized his greatness more quickly than most of his contemporaries did. Without the support and enthusiasm of Peter Garland, James Tenney, Charles Amirkhanian, Eva Soltes, and others, Nancarrow’s fate could well have been that of Charles Ives or Harry Partch; he might have been another unique, seminal American composer who never received proper recognition in his lifetime.

Happily, this possibility is now impossible. 1750 Arch Records has been steadily releasing all the Studies, and more and more people have come to enjoy the unique beauty of Nancarrow’s music. His treatment of density and speed; his urge to realize sounds never before heard; his pragmatic, get-it-done attitude, which has led him to get extraordinary results from the most ordinary of instruments – these qualities speak to a profound need in musicians and audiences alike, and they have placed Nancarrow at the forefront of contemporary American music.

(This essay first appeared in Keyboard Classics, May/June 1984, under the title “The Great Player Piano Revival: A Newfangled Approach.”)

Link to:

Music: Essays: Contents

For more on Conlon Nancarrow, see:

Film Dreams: Luis Buñuel

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music Book: Soundpieces: Interviews with American Composers

Music Lecture: “Intense Purity of Feeling”: Béla Bartók and American Music

Music Lecture: My Experiences of Surrealism in 20th-Century American Music

Music Lecture: The Secret of 20th-Century American Music

Music: SFCR Radio Show #26, Surrealism in 20th-Century American Music