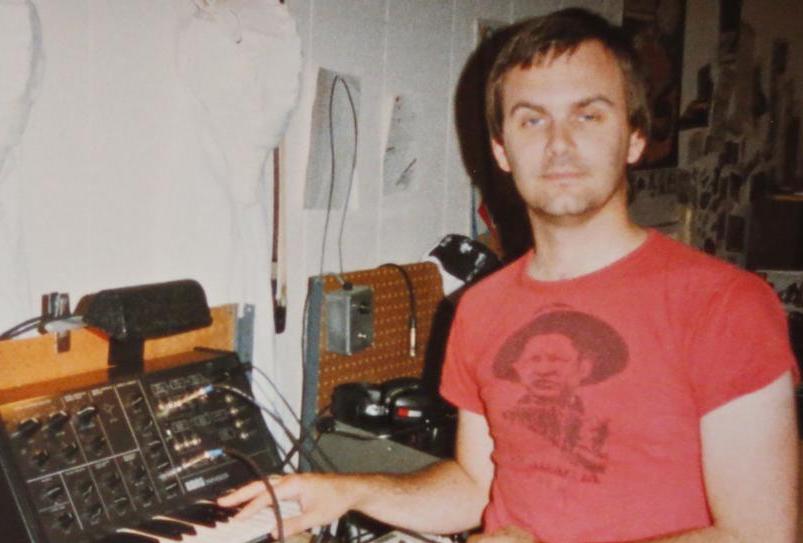

Philip Perkins and His Music

It is reported that, in a particularly hysterical moment, Mahler envied Beethoven his deafness: There was someone totally free from the distracting sounds of the world, someone who could create his own sonic universe with perfect attentiveness. Mahler’s lament is emblematic of the traditional concert-music attitude toward both composition and dissemination: Get in that soundproof room, shove those twelve tones around, and then get a bunch of people in another soundproof room and have your piece played for them. The result, of course, is the situation Cage described: Music reduced to “a vehicle for pushing the ideas of one person out of his head into somebody else’s head.”

At first, composer Philip Perkins would seem to be Mahler’s opposite. In Apartment Life, Perkins uses recordings of day-to-day urban sounds to create what he calls “an apotheosis of a great, ever-changing city song that continues night and day all around us.” Perkins’ greatest musical asset is his unMahlerian appreciation of that ongoing song. (In fact, were we to push him to an hysterical extreme, Perkins might cry out for blindness, so that visual impressions wouldn’t distract him from the aural activities around him.)

Nevertheless, Perkins and Mahler enjoy more common ground than first meets the ear. Mahler absorbed the sounds of his youth – nature and rural life – and transformed them into his symphonies. Perkins goes a step further, using the actual sonic events of urban and suburban life for his music. But he uses them with a gourmet’s appetite for “banality” which is utterly Malherian. All the familiar stuff is there: construction noises, dogs, buses, unintelligible voices, birds, a downstairs neighbor playing disco records, wind, children off playing somewhere. These sounds are musicalized through a variety of electronic processes, and not just slapped onto a record or cassette. Yet Perkins manages never to destroy their basic integrity – and by preserving that, he preserves their ability to heal us.

Here then is the real difference between Mahler and Perkins. If Mahler is going to heal people, it’ll be by making them ride the roller coaster of his ego, with all its dramatic conflicts and spiritual obsessions. Perkins realizes that only we can heal ourselves, through our own attitudes, our own calm and peace with the world around us. Unlike Mahler, Perkins doesn’t want to be liberated from the world; he wants to be liberated by it. Not an easy task, when you consider the abrasive nature of contemporary American life. But Perkins is an artist of rare talent, and the success he achieves is remarkable.

Part of the secret of this success is Perkins’ sophisticated feeling for timbre. Take, for example, two sections of Apartment Life. For “Ear to the Ground,” Perkins used a contact mic on a large concrete and steel foundation to record ever-changing deep bass harmonics, which he then further alters. In “Party Mix,” he manipulates the voices of several simultaneous conversations into one sustained event of amazing beauty. Equally impressive for their timbral invention are the four “Bird Variations” on his album Neighborhood with a Sky. In these, mysterious rustlings and activities are melted into staticism; machinery, voices, nature, and electronic sound fuse into four haunting aural landscapes.

Vital to the beauty of all these pieces is Perkins’ highly developed sense of duration. Not unlike Morton Feldman, Perkins has a very astute feeling for how long he can sustain an event before it should either be altered or replaced by something else. His music is almost never overlong or monotonous – in fact, I sometimes wish he would dwell longer on some of his pieces.

Perkins’ music is not based exclusively on recorded sounds. His sensitivity to the basic sonic stuff of American life is expressed in his facility for Americana noise. His gift for a sweet, folksy sound is most notable in a charming piece on Neighborhood, “The Black and White Cat.”

This feeling for Americana is also used more self-consciously: In Neighborhood’s “Retreat,” a chunk of an old country western recording is smoothly introduced into a piece otherwise dominated by the sounds most suggestive of garbage trucks and water gurgling down a series of drains.

As the description of “Retreat” suggests, there is also a streak of humor in Perkins’ music – more as a gentle sense of amusement than as outright musical jokes. The humor comes from the unusual juxtaposition of sounds; a fundamental aspect of city life, where millions of people simultaneously perform their own peculiar, noisy lives. There is a quiet comedy to “Rico in the Birdhouse,” where a live trombonist performs elaborate multiphonics in a zoo’s birdhouse (which seems to contain even more children than birds). My own favorite is “Reading the Mail” in Apartment Life: Perkins picks up a CB conversation and distorts it with both changes in reception and his own studio and tape alterations. Part of the piece’s deadpan humor is the unexpected, but not inappropriate addition of organ chords under the speech of an amazing CB character who calls himself the Wolfman. The vocal timbre of the Wolfman is as striking and vivid as a characterization by The Residents. (Incidentally, among the people thanked on Neighborhood are “the Grove St. boys.” Hmmm…)

The most extraordinary feature of Perkins’ music is the way it generates a truly childlike sense of wonder and fascination. In listening to his pieces, we become witnesses to events without knowing their references or associations – essentially, the perspective of a child. It is rare enough for a filmmaker to re-create this deeply resonant feeling; in music, the effect is virtually unprecedented. (There are glimmers of it in Ives and Cage.) Through the same means, Perkins also creates the illusion of slow motion. Sounds enjoy a freer, more unhurried tempo, one that we don’t ordinarily recognize in our haste to link them causally with other sounds. The result is a gentleness and peace that give Perkins’ music its special beauty. Even the gusty winds and noisy dogs of “Este’s Request” have nothing ominous about them. By refusing to place them in the dramatic or causal contexts with which we associate them, Perkins makes them both more immediate and less specific. It’s not the wind threatening a farmhouse or even the wind outside your window, but Wind; not dangerous dogs snarling at you, but Dogs. Listening to his music, you become more conscious of their beauty and uniqueness. With a little effort on your part, that awareness can carry you through your encounters with them – or with buses, construction, and even downstairs disco – in any and all contexts. That’s quite a benefit.

(This essay first appeared in OP “P” Issue, March-April 1983.)

Link to:

Music: Essays: Contents

For more on Philip Perkins, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition