Some Thoughts Toward an Appreciation of Richard Strauss

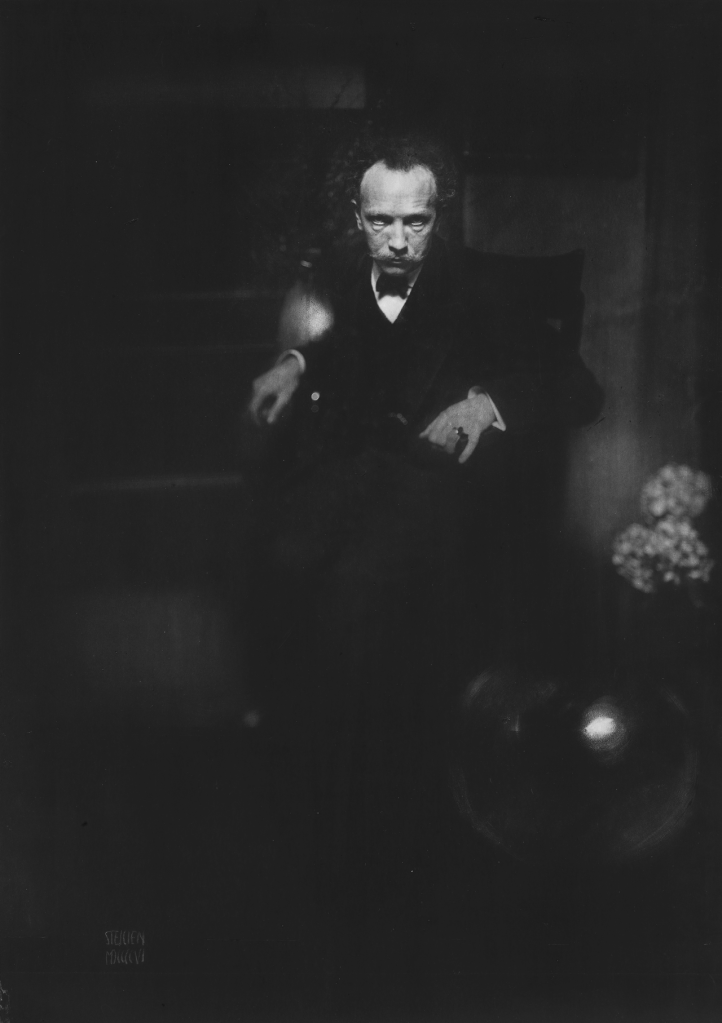

Reading Herta Blaukpopf’s invaluable book Gustav Mahler – Richard Strauss Correspondence 1888–1911 made me realize something that is obviously true, yet never acknowledged: If it had been Strauss who died in 1911, instead of Mahler, Strauss would today be universally revered as one of the cornerstones of 20th-century music. He would epitomize the rare talent that seems to continuously ascend, starting in his early twenties with his breakthrough scores of the 1880s, the Burleske for piano and orchestra and the orchestral tone poem Don Juan, through the epic strangeness and originality of his masterworks that followed – Tod und Verklärung, Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche, Also sprach Zarathustra, Don Quixote, Ein Heldenleben, Symphonia Domestica – and culminating with his three classic operas in the early twentieth century: Salome, Elektra, and Der Rosenkavalier. The searing dissonances and ambiguous tonalities of the first two operas would place Strauss firmly among the boldest modernists of the 1900s; the melody and humor of the third would make plain that this composer could do anything and do it brilliantly. Such a stunning flow of music, reaching its terminus with Rosenkavalier’s premiere when Strauss was 46, would have provoked an international flood of sorrow and regret, one that would still ache in the 21st century.

Strauss however died in 1949 at the age of 85, and today he is not regarded as any kind of cornerstone at all – despite the fact that he actually did create all that music from the 1880s through 1910. And despite the fact that he continued to produce great works in the last 38 years of his life: Every decade, from the teens through the forties, saw the composition of major scores. Yes, Strauss was compromised by Germany’s descent into fascism and his dealings with the Nazi regime, distant and perilous though those dealings were for him. Yet the eclipse of his reputation cannot be attributed to that stain alone; no one seriously interested in 20th-century music questions the importance of Anton Webern’s works, even though Webern’s Nazi sympathies are well known.

The truth is, Strauss simply did not develop the way one would have conjectured at a 1911 gravesite, and the redirection of his music over the first half of the 20th century has been held against him. In the 1900s he journeyed out as far as he cared to; starting in the 1910s, he chose to pursue a different trajectory, one that he kept to for the remainder of his life. Der Rosenkavalier was not the light-hearted and melodic cherry topping a modernist confection – it was a new gauntlet Strauss had thrown down, a declaration that he did not want to move beyond the extremes of Salome and Elektra, that he wanted to remain within the tradition he knew and loved. Elektra, like Salome, created an international sensation after its premiere in 1909; but this more radical follow-up to Salome did less well financially than its predecessor had, while the tuneful and funny Rosenkavalier did business that eclipsed Salome’s. How many other composers have known similar encouragement to follow the direction that they wanted to pursue?

Remaining within the tradition, however, Strauss was still able to redefine musical conventions. Der Rosenkavalier also represented another line he had drawn in the sand, his demonstration of a new approach that came to characterize 20th-century opera: the elimination of the heroic tenor. Although Strauss deeply reverenced the operas of Richard Wagner, his own work shows no feeling at all for the heldentenor. His first opera Guntram, composed in 1893 to his own libretto, is his only attempt in this direction, and the disconnect between creator and protagonist is there for all to hear. Guntram is the same type of goody-goody that would again defeat Strauss some twenty years later, with his 1914 ballet score Josephs Legende: “The chaste Joseph himself isn’t at all up my street,” he groused to Hugo von Hofmannsthal, co-author of the ballet’s scenario, “and if a thing bores me I find it difficult to set to music.”

After Guntram Strauss composed another fourteen operas over five decades, from the 1900s through the 1940s, and in none of them is the tenor the hero. Strauss was more interested in the relationship between baritone and soprano – the basic pairing in Feuersnot, Salome, Elektra, Die Frau ohne Schatten, Arabella, Friedenstag, and of course the autobiographical Intermezzo, in which those two voices represent Strauss himself and his wife Pauline de Ahna (a celebrated soprano who sang in Guntram’s premiere). Tenors in Strauss’ 20th-century operas are monsters like Herodes in Salome and Aegisth in Elektra; they’re deceivers such as the Baron in Intermezzo, the nephew in Die schweigsame Frau, Leukippos in Daphne, Midas in Die Liebe der Danae. Midas’ touch turns Danae into a golden statue in that opera; in Die Frau ohne Schatten, it’s the tenor Emperor who’s petrifying into a statue rather than making himself useful. Worse than useless is the tenor Menelas in Die ägyptische Helena, who almost kills Helena, goes crazy, and kills other people.

The choreographer George Balanchine famously declared, “The principle of classical ballet is woman.” Strauss could have said the same thing about opera. Both Elektra and Der Rosenkavalier proved to him that all he really needed were female voices. The central conflict in Elektra is between daughter and mother, with Orest and Aegisth serving as supporting characters, male extensions of the personality and will of Elektra and Klytemnestra, respectively. Baron Ochs in Der Rosenkavalier may have been the original focus of Hofmannsthal’s libretto – the opera’s working title was Ochs auf Lerchenau, and Hofmannsthal fretted that the audience would lose interest after Ochs’ departure in Act Three – yet he is actually the opera’s least interesting role, a clichéd heavy designed to be ridiculed and dismissed. Instead, Rosenkavalier reaches its greatest height in its Ochs-free conclusion, an exquisite trio for two sopranos and mezzo-soprano – the music that would be performed at Strauss’ funeral, at the composer’s request.

Strauss’ focus on women in his operas is obvious simply from a survey of their titles: Salome, Elektra, Ariadne auf Naxos, Die Frau ohne Schatten, Die ägyptische Helena, Arabella, Die schweigsame Frau, Daphne, Die Liebe der Danae – that’s nine out of fifteen. Strauss’ only 20th-century opera named after a man is Der Rosenkavalier – and that male role is sung by a woman.

To create such a compelling roster of female characters, a certain self-identification has to be at work. It’s no accident that the role of the Composer in the Prologue of Ariadne auf Naxos is sung by a mezzo-soprano en travesti, a device imposed by Strauss over the protests of his librettist Hofmannsthal. With Ariadne’s Composer, Strauss was exhibiting more than just nostalgia for the trouser role of Octavian, the hero of Der Rosenkavalier; he was acknowledging a duality in his own nature. This duality also characterizes the vivid portrait of his own wife in Intermezzo: When “Christine Storch” is seen getting dressed in Act One – and chiding the hired help and lamenting her domestic responsibilities and complaining about her husband – the witty activity in the orchestra is so busy and detailed that the music becomes an elaborate form of impersonation, as though the composer was the one who was getting all dressed up as Christine.

A not dissimilar impulse of self-identification is also at work in Strauss’ orchestral tone poems. He launched his career by animating a series of male ego images: Don Juan, the great lover; Till Eulenspiegel, the clowning prankster; Zarathustra, the revolutionary philosophical thinker; and Don Quixote, who is simultaneously a lover and a clown and a philosopher. But from there Strauss proceeded to make art directly about himself (and Pauline), in a veiled manner with Ein Heldenleben and then explicitly in the 20th century with Symphonia Domestica and Intermezzo.

It’s very telling that Strauss’ only weak tone poem in the eleven years from 1888 and Don Juan to 1898 and Ein Heldenleben is the seldom-performed Macbeth, a flat and derivative work that never succeeds in holding an audience. Granted, this score was his first literary tone poem, and he was still coming to grips with the demands of the genre; but despite its 1892 revision, the piece stubbornly refuses to come to life. Strauss famously remarked that he wanted “to be able to depict in music a glass of beer so accurately that every listener can tell whether it is a Pilsner or a Kulmbacher,” yet no one can listen to his Macbeth cold and hear in it the story of an ambitious man losing his soul to diabolical forces – much less the machinations of witches in Scotland!

I suspect that the inadequacies of Strauss’ Macbeth are rooted in its lack of any deep personal connection: He may have had ambitions, but he plainly did not see himself as a tragic figure. Tragedy does not mark any of his other tone-poem protagonists, even though they are all made to confront failure and mortality. Neither is tragedy reflected in the self-referential Heldenleben or Domestica or Intermezzo; if anything, Strauss was quicker to see (and hear) the humor of what was happening in his life. In using Sophocles’ play for his landmark opera Elektra, Strauss revealed the depth of his understanding of tragedy, working with his librettist Hofmannsthal. Composing Macbeth on his own, however, tragedy eluded him.

The irony is, while Strauss was anything but a tragic figure in the 19th century, he eventually became one in the 1930s and ‘40s. In certain ways he reminds me of James Tyrone, the father in Eugene O’Neill’s play Long Day’s Journey into Night: a gifted artist who undermined his own life and career by clinging to material success once it came his way. Strauss understood that the stature and specialization he had achieved in opera over the 20th century was contingent upon his remaining in Germany. Otto Klemperer supposedly observed that Strauss refused to leave his homeland after Hitler’s rise to power because Germany had fifty opera houses and the United States had two. In 1980 Philip Glass told Tracy Caras and myself, “Opera is the only vein of gold that I’ve found in the music business.” How much more true that was in Germany half a century earlier, I don’t need to explain.

Strauss initially attempted to tap that golden vein with Guntram and Feuersnot, but both operas were misfires rejected by the public. Not until Salome did opera give itself to Strauss – and then it gave itself completely. When he was questioned about the supposed immorality of Salome – an opera so controversial that the Viennese Court refused to let Mahler conduct it – Strauss pointed to his home in Garmisch and said that he’d built it with the royalties from Salome. He really loved that house too and did most of his creative work there for the rest of his life. Even Hitler couldn’t get him out of that house – Nazis goose-stepping up and down outside his window, Strauss didn’t care, he was staying put! By 1943, when he finally realized that he needed to flee, it was too late: The Gestapo refused to let him leave the country. Not until the end of World War Two, after the American military commandeered his house, did he pack up and go to Switzerland. It was only in the last fifteen months of his life, after being cleared in his 1948 deNazification hearing, that he was able to return to his home.

When Ken Russell made Dance of the Seven Veils, his scathing 1970 biopic of Strauss, he emphasized the opening of Also sprach Zarathustra to insist that Strauss was a believer in the myth of the Aryan superman, a proto-Nazi content to work with Hitler’s regime decades later. In fact Strauss despised the Nazis and their bigotry and violence. He did what he could to placate the regime in order to protect his family because his daughter-in-law was Jewish; and while he was able to keep her and his grandchildren from being murdered by the Nazis, that protection could not be extended to the rest of her family. Eventually Strauss became persona non grata with the Nazis, although they tolerated his presence in Germany because he and his music were too famous, both at home and around the world, for them to liquidate him and ban his works.

A second degradation that has attached itself to the opening of Zarathustra is attributable to another filmmaker: Stanley Kubrick, who appropriated Strauss’ fanfare for his 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Endless science-fiction-themed quotations have followed ever since, yet even these lazy repetitions cannot blunt the essential strangeness of Also sprach Zarathustra. I recall listening to Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche, composed a year before Zarathustra, and during an early passage that represents Till overturning goods at the marketplace, I thought to myself, This music is strange. And Strauss does indeed take that score through some very odd contortions in depicting Till’s merry pranks.

Also sprach Zarathustra is even stranger: In section 7, “The Convalescent,” after a volcanic restatement of the opening fanfare theme, the piece goes completely bonkers, evoking a space of pure potentiality, a realm of the mind where all bets are off. I remember listening to that music careening off the walls and again thinking to myself, This music is strange. Then I suddenly realized whom Strauss reminded me of: Carl Stalling. Both composers become strange for the same reason, they’re trying to trace narrative. And when narrative logic governs musical form, you get some strange transitions and juxtapositions and simultaneities. Stalling, trying to keep up with the action in the Warner Bros. cartoons, is simply a condensed and intensified version of the same aesthetic Strauss had pursued.

The strangeness of Also sprach Zarathustra, however, is not limited to its seventh section; it characterizes the entire work, making it perhaps the greatest of all Strauss’ orchestral scores, because Zarathustra holds together the most extreme and disparate musical materials. This 1896 composition features a twelve-tone theme, used for a fugue in section 6, “Of Science”; then, after the tone poem has been at its wildest in “The Convalescent,” it settles into section 8, “The Dance Song”: a fiddler’s waltz, which the whole orchestra takes up – a gorgeous tune too! For Strauss, there is no difference in going from one to the other. If both exist in his ear, then they can jolly well exist side by side on the concert stage.

An equally wild juxtaposition occurs in Strauss’ Two Songs to Poems by Nikolaus Lenau, his Opus 26 for voice and piano, composed in 1891. He sets the delightful “Frühlingsgedränge,” about the arrival of the enchanting Children of Spring, with a bubbling charm in the piano and a euphoric vocal line; but that song is followed by the dark and despairing “O wärst du mein!,” a highly chromatic, tonally ambiguous outcry over unattainable love. The song’s sorrow is made more bitter still when the piano stops playing as the singer declares, “For this I cannot forgive my fate.” That silence is counterbalanced by the piano’s extended funereal diminuendo at the end, the voice having fallen silent after confessing that the sight of friends in their coffins, “corpse by corpse, is less painful compared to the agony of never making you my own.”

Perhaps the most striking instance of Strauss combining disparate extremes is his Two Pieces for Piano Quartet, composed in 1893. The two pieces are entitled “Arabian Dance” and “Love Ditty,” and while the latter sweetly waltzes by in six minutes, the former is a propulsive 90-second attempt to evoke Middle Eastern music on violin, viola, cello, and piano. I don’t know if Strauss had heard any Arabic music or if he just made up this score out of whole cloth, but to take that most staid of chamber-music ensembles, familiar from endless high-class restaurants and hotel lobbies and ocean liners, and have them play this “Arabian Dance,” followed by pure Viennese Schlagobers, insisting that the two are equivalent in this context – that was something nobody else was doing in the 19th century. Or for much of the 20th.

A further instance of 1890s strangeness from Strauss, and maybe the most unexpected and surprising, characterizes his 1899 melodrama for reciter and piano, Das Schloss am Meere. The text, written in 1839 by the poet Johann Ludwig Uhland, describes a majestic seaside castle, whose royal occupants now walk alone in sorrow after the death of their daughter. I was genuinely startled upon first hearing Strauss’ piano accompaniment to this poem: A familiar-enough introduction is stated, and then the piece takes off into the idiom of the mature piano music of the Russian composer Alexander Scriabin. So unsettling was this reinvention of Strauss’ sound that I sought out the opinion of Bruce Posner, a pianist thoroughly versed in Scriabin’s composition. He heard it too and told me, “Middle- to late-period Scriabin definitely makes itself known starting at 16 seconds in … And yes, the pieces Scriabin was composing at this time – such as the Op. 25 mazurkas – are less advanced [than Das Schloss am Meere is] … It’s a musical UFO sighting.”

Strangeness is not confined to Strauss’ 19th-century compositions, however. One highly unusual aspect of his 20th-century music is Strauss’ repeated use of the orchestra to depict sexual intercourse. Most well known is Symphonia Domestica and the love scene in its Adagio, representing the composer’s nocturnal intimacies with his wife. (When Ken Russell featured this passage in Dance of the Seven Veils, he showed Richard and Pauline going at it in a large bed in the middle of the orchestra.) But what about Strauss’ second opera Feuersnot, premiered in 1901? The wizard Kunrad, having extinguished all fire in the town, declares his need for “an impassioned virginal body” if the vital element is to be restored. Diemut, who had initially spurned Kunrad’s attentions and then lured him into a humiliating prank, offers her body to him, and what follows is an orchestral interlude as they make love. And then there’s Strauss’ more celebrated 1932 opera Arabella, in which Arabella’s younger sister, the male-presenting Zdenka, slips out of her boy’s clothes and sleeps with her beloved Matteo, all the while pretending in the darkened room to be Arabella, who is the object of Matteo’s infatuation. The third act begins with an orchestral prelude representing their lovemaking. For that matter, what are the exquisite love themes in the tone poem Don Juan if not metaphors for the title character’s erotic encounters? But while the Don is strictly whiz-bam-thank-you-ma’am, in both Feuersnot and Arabella the sex act leads to the recognition of genuine deep love between the man and the woman. By the same token, the rapturous love music in Domestica reveals one of the secure foundations in a marriage that can be tempestuous during the day.

In the 20th century Strauss left programmatic music behind him after his last great symphonic works, Symphonia Domestica and Eine Alpensinfonie, and so this strangeness mostly disappeared from his orchestral composition. The most significant exception came when he was in his early sixties, with his 1925 Parergon to Symphonia Domestica. In this concerto for piano left-hand and orchestra, Strauss’ Opus 73, the orchestra becomes unexpectedly visceral, especially in the tilting glissandi of its central section. The Parergon is both more successful and more extreme than its companion piece, the Panathenäenzug, his Opus 74, composed a year later. The two concerti were written for Paul Wittgenstein, brother of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and a concert pianist who lost his right arm during World War One. Maurice Ravel most famously rose to the challenge of composing a concerto for him; others from whom Wittgenstein commissioned scores include Sergey Prokofiev, Paul Hindemith, and Benjamin Britten. What has held back Strauss’ concerti, both rarely performed or recorded, is of course their appalling titles. Wearing his Classical Greek erudition on his sleeve, Strauss burdened these works with the most unpronounceable and obscure names that could be imagined, and this has been and will always be the kiss of death for them both.

Which is especially unfortunate, because these concerti represent a particularly vital time for Strauss, composed during the brief years between his two great operas of the 1920s, Intermezzo and Die ägyptische Helena, his Opp. 72 and 75, respectively. Both operas are of special interest: Intermezzo demands attention because of its unabashed self-portrait (and its remarkable waltz interlude in Act One, which plays against the rhythmic conventions of the genre), while Die ägyptische Helena stands as Strauss’ most compelling piece of Hofmannsthal exotica, its vivid orchestration and dramatic use of mythic themes surpassing the grab-bag, revue-like Ariadne auf Naxos as well as the lumbering allegories and overly dense plotting of Die Frau ohne Schatten. In both characterization and story line, Die ägyptische Helena – like Intermezzo – is far more distinctive and precise and engaging than either of Strauss’ aforementioned operas from the teens.

My estimation of Strauss’ 1920s operas is, I admit, a minority opinion, as enthusiasts for Ariadne and Die Frau still hold sway. Time has already begun to improve Intermezzo’s reputation, however, and I am convinced the same will happen to Helena, once someone finally stages it in a first-rate production. But while I have no apologies for my take on these works, I do deeply regret the unthinking and dismissive entry on Strauss, which I wrote for my Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, published in 2012; even more shameful is my failure to correct it when given the chance to revise and expand that book for its second edition of 2019. The truth is I didn’t know any better back then – my enthusiasm for the music of Richard Strauss is an enlightenment that was not visited upon me until the 2020s. And it arrived only because I decided to stop remembering the opinions I had formed in the 1970s, and instead set out to listen seriously to his music. Once I did, I heard how totally wrong I had been in clinging to my old belief that these works were all on the surface – nothing could be further from the truth. His music is deep, it is moving, it is honest, it is personal, and most importantly of all, it is beautiful. I may not be given the good fortune to prepare a third edition of my dictionary, and so in a spirit of sincere contrition and an earnest desire to set the record straight, I end this essay of appreciation with a rewrite of that entry. All readers should feel free to print out what follows and paste it into their copies of my book.

STRAUSS, RICHARD (1864–1949). German composer and musician. Richard Strauss studied composition with Friedrich Wilhelm Mayer in 1875 and wrote skillful if conservative works in the 1880s, including his Serenade (1881) for wind ensemble, Cello Sonata (1882), Horn Concerto No. 1 (1883), and Suite (1884) for thirteen winds. Upon absorbing the music of Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, and Richard Wagner, Strauss developed a livelier and more imaginative voice, with such works as his Burleske (1886) for piano and orchestra and the orchestral tone poem Don Juan (1888). A programmatic score in the Lisztian tradition, Don Juan employed unusual melodic materials featuring wide and sudden leaps. Strauss became an international sensation as a composer and also established himself as a conductor with the orchestral scores that followed: Tod und Verklärung (1889), Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche (1895), Also sprach Zarathustra (1896), Don Quixote (1897), and Ein Heldenleben (1898).

His orchestral program music ended with Symphonia Domestica (1903) and Eine Alpensinfonie (1915), but Strauss won further renown with two landmark operas, Salome (1905) and Elektra (1908). They featured harsh dissonances and dramatic extremes of expressionist intensity, but their orchestral brilliance and vocal bravura secured their place in the repertory. With the tuneful and lighthearted Der Rosenkavalier (1910), Strauss composed his most popular opera and turned away from the modernism of his previous works. Hugo von Hofmannsthal wrote the libretti of Elektra and Der Rosenkavalier, and their collaboration continued with Ariadne auf Naxos (1912; rev. 1916), Die Frau ohne Schatten (1917), Die ägyptische Helena (1927), and Arabella (1932); Strauss himself wrote the libretto for his witty autobiographical opera Intermezzo (1923). He also anticipated the neoclassical trend that emerged in the 1920s with Der Bürger als Edelmann (1912), his music for Molière’s play Le bourgeois gentilhomme. Most notable among his later operas are Daphne (1937) and Die Liebe der Danae (1940), both employing Greek mythology, and his final opera, Capriccio (1941), which reflects on the dilemmas of opera composition.

By then Strauss was the grand old man of German music and had formed an uneasy alliance with the Nazi government. He included an electronic-music instrument, the Trautonium, in the scoring of his Japanische Festmusik (1940) for orchestra. Most of the music of his final years, however, were intimate pieces for smaller forces, which marked a return to forms he had first utilized in his teens, such as his Horn Concerto No. 2 (1942) and his Sonatinas Nos. 1 (1943) and 2 (1945) for wind instruments. Especially admired are the haunting Metamorphosen (1945) for 23 strings, a lament at the destruction wrought by World War Two; the rhapsodic Oboe Concerto (1945, rev. 1948); and Strauss’ moving contemplation of death in the Vier letzte Lieder (1948) for soprano and orchestra. See also BARTÓK, BÉLA (1881–1945); ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC; KORNGOLD, ERICH WOLFGANG (1897–1957); QUOTATION; SCHOENBERG, ARNOLD (1874–1951); SZYMANOWSKI, KAROL (1882–1937); TWELVE-TONE MUSIC; VARÈSE, EDGARD (1883–1965).

(This essay, written in 2022, appears here for the first time. Special thanks to Bruce Posner and Sabine Feisst for all their help!)

SOURCES

“The chaste Joseph himself”

Michael Kennedy, Richard Strauss: Man, Musician, Enigma. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 183

“The principle of classical ballet is woman”

Fiona Lewis, “To Balanchine, Dance Is Woman – and His Love” in The New York Times, October 6, 1976.

“to be able to depict in music a glass of beer”

Kennedy, Richard Strauss, p. 122

“Opera is the only vein of gold”

Nicole V. Gagné and Tracy Caras, Soundpieces: Interviews with American Composers. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1982, p. 221

“For this I cannot forgive my fate”

Strauss: The Complete Songs – 2. Hyperion CDA67588, cd booklet. Richard Stokes, trans., p. 6

“Middle to late period Scriabin”

Letter to the author, 6 April 2021

“an impassioned virginal body”

Feuersnot, cpo 777 920-2, cd booklet. Susan Marie Praeder, trans., p. 72

Link to:

Music: Essays: Contents

For more on Richard Strauss, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music: KALW Radio Show #1, A Few of My Favorite Things…

Music: KALW Radio Show #6, Gender Variance in Western Music, part 2: Female-to-Male Representations