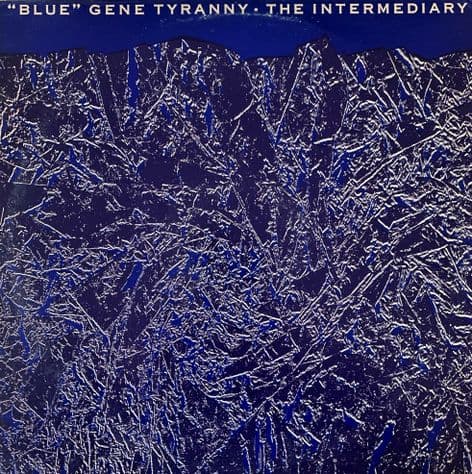

The Intermediary

Tyranny’s piano improvisation for The Intermediary (1981) was recorded “in Geneva in January of ‘81 at 4 o’clock in the morning. Peter Gordon was producing his own music, music by Jill Kroesen, music by me, in this month of manic recording. He got a sponsor who booked a whole month at a recording studio in Geneva, Aquarius Studios, booked us rooms up on top and just said go to it and record everything you can, and we did. We produced a lot of music. It was a fantastic opportunity. That particular recording was done almost the last day I was there. It was just one take, exactly as it is. Jean Ristori put on the tape and I started playing. I said, let me know a couple of minutes before the tape ends. Then they’d stop and put on another tape, and I’d start playing and that’s it. So it’s very direct playing. At 4 o’clock in the morning, you’re really open! At the time I played, I just had this idea of openness and this idea of playing three or four different kinds of characters. Sort of like you’re telling a story and finding ways for these characters to talk to each other.”

And what talk – pastoral, pop, Americana (even unto the Native American feel of the opening theme), melody, reverie, dance… I remember speaking with Robert Ashley shortly after he’d heard a tape of this performance, and how excited he was by the playing. “It’s like Gershwin,” he said with awed delight. (I mentioned his comparison to Tyranny, who remarked that Teddy Wilson would be closer to it – “I like Gershwin, but not that much.”) I think a lot of people would agree with Ashley (or Tyranny), simply from the exuberant playing that wound up on Side Two of The Intermediary. But I believe Ashley was hearing something more, something I hear too, throughout all the playing. It’s the same hit I can get from Gershwin, a feeling of inexhaustible vitality and enthusiasm and technique. Also a feeling of observing something both original and highly personal, because “amusing as it may be to find traces of antecedents,” as composer Joe Hannon said of the album, “Tyranny has forged a voice of his own with which he communicates compellingly. And it swings.”[1]

This improvisation was a breakthrough for Tyranny, in part simply because he’d gotten it on tape: “It’s a very personal way of playing. I’d never really been able to record that, because it’s so personal; it’s ways I would play for myself […] It was amazing that it happened, and since then I’ve been able to do it in public. […] I have a lot more faith in just letting go.” He was raised that morning as he would say, “to another type of communication.” The dialogue of the musical characters was just the most observable byproduct of this heightened communication, where the pianist was one soloist in an ensemble of soloists.

In an attempt to observe, at least metaphorically, the mysterious dynamics of that communication, Tyranny decided to begin again with his improvisation, re-scanning it into The Intermediary, where you hear his playing from the inside as well as the outside. The LP is a meditation on the experience of realizing that performance, a work of reportage and analysis just as much as The White Night Riot or Harvey Milk (Portrait). And like the Portrait, The Intermediary uses electronics to trace the paths of the invisible, animating energy that contributed to an external event. Working with Joel Ryan’s programming, Tyranny repeatedly passed the original piano track through a computer, triggering an array of electronic reinventions of his playing. “Joel had created this program that created 16 oscillators and made accessible the frequency and amplitude of each of these oscillators by literally changing the keys”, Tyranny explains. “Then those oscillators would also be resonated by the frequencies of the piano that we were putting in, which became a sort of overall voltage; whether it’s frequency, amplitude, phase, or time, it comes out as voltage. We tuned the oscillators to create various tunings and just experiment it with that.” He selected the fragments of electronics which appealed to him and incorporated them into the piano track, “somewhere in relation to where the piano was making those same gestures, before or after or during, so that the direction of cause and effect was played with.”

Few musicians would have the nerve to monkey around with one of their most accomplished performances, but Tyranny isn’t interested in persuading people that he can play the piano. He saw the improvisation as an opportunity for discovering more, and for sharing that spirit of discovery with others. In blending the electronics with the piano, he was following John Cage’s idea of destroying intentionality by multiplying intentionality. Because for all of Ryan’s and Tyranny’s expertise, that additional dose of intentionality came out with a non-intentional luster all its own. “The interaction between the computer and the piano was very mysterious,” says Tyranny. “Things would create this very amazing phasic information from side to side and in sudden interior-depth illusions, or certain things would resonate almost independently of what piano pitches were coming in. It was really mysterious, the translation of the voltage of the piano, the shadow of the piano gesture, with this pre-tuned computer.”

Besides obscuring the ego of the pianist, the cryptic, otherworldly computer music also counterbalances the piano’s familiar intimacy, its ‘humanness.’ Tyranny is of course light used beyond that old wheeze of The Struggle Of Man Against Machine. He just wants to remind us that there are many levels to the experience of humanness, and that we should try to perceive more than what’s on the surface. The Intermediary, therefore, is as much about the computer as the piano – it isn’t piano playing with a side order of electronics. Some of the most striking gestures are when the piano and computer coincide. Sometimes you glimpse only flourishes of the electronics, glistening and popping, when the piano textures thin; at other moments, when Tyranny’s playing is especially raucous and dense, they seem to billow out from the piano like smoke from a fire. Whenever the computer music appears, it’s both strange and familiar; no matter how weird or unpredictable it sounds, it always fits – on some level, you really do hear its connection to the piano’s music. A few of the piano transformations are even recognizable: That great gallop heard a little more than three minutes into the second piano section of Side Two plainly engendered the electronics that resound at the end of the piece.

Like all good collaborators, the computer also gets to take center stage: it opens and closes the album and enjoys two extended solos. Timbrally, The Intermediary’s electronics vary from metal percussion to wayward radio signals. (At the opening, they’re particularly warm and rich, more like a distant carillon or organ than electronic music.) Yet there is a consistent character throughout this range of beautiful sound. The computer music is a genuine presence, whether it’s replacing the piano or accompanying it. Eventually, you get the feeling that it’s communicating with the pianist even when it isn’t sounding at all. Tyranny’s subtle treatment of dynamics even creates the illusion of changing spatial relationships between the electronics and the piano, as though there had been a pair of musicians in the studio.

This phantom partnership between the instrumentalists reminds me of Charles Ives’ use of offstage musicians in his Piano Sonata No. 2, “Concord, Mass., 1840–1860.” To suggest the transcendental experiences of the sonata’s characters, Ives included the option of incorporating a viola in the “Emerson” movement and a flute in “Thoreau.” The Intermediary, which combines composer, performer, and musical characters, takes this idea even further; the ‘offstage’ electronics describe the receptivity of all The Intermediary’s participants – including, ideally, that of the listeners as well.

The Intermediary defines both piano player and piano playing as a conduit. The piano isn’t a mirror or a movie screen, but a window, and an open one at that. In the “Concord” Sonata, Ives depicts Thoreau’s realization “that he must let nature flow through him and slowly – he releases his more personal desires to her broader rhythm.”[2] Both Ives and Tyranny are fascinated by the experience of an intermediate state of consciousness, and they attempt to describe this state in their music. In “The Alcotts,” when Ives thunders out a quote from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, it’s accompanied by high tones that have no overt bearing on the motto itself. They indicate the distance the music has travelled to reach us and hint at the realm from which it originated. That’s the aesthetic premise of The Intermediary, and so when Tyranny’s playing reaches certain peaks of intensity (such as early in the second piano section of Side One), it’s attended by otherworldly electronics.[3]

By combining computer and piano, The Intermediary is another vision of the ensemble of soloists. Pursuing that ideal relationship further, Tyranny subsequently created a concert version of this piece, in which he improvises to a 20-minute tape, “a simple progression time-delayed seven times and shifted to seven different frequencies based on the harmonics of the fundamental.”[4] Performance requires a sound engineer who improvises the spatial shifting and selection of the tracks, and thus makes the tape mutate kaleidoscopically. I’ve heard Tyranny play the piece several times in collaboration with Paul Shorr, and when Shorr would really start feeling his Cheerios, he’d alter not just the tape but also the sound of Tyranny’s amplified piano. Building in uncontrollable insurrections is a standard deconditioning technique with some of the free improvisers, and the live Intermediary can sound like them, especially when the tape’s pulse relaxes. Tyranny rolls with the punches as they would: His playing becomes more dissonant and amelodic, and he unearths treasures of noise-making from the piano’s new timbres. That’s what can happen when the person talking in tongues has the genius to listen in tongues at the same time.

FOOTNOTES

1. Joe Hannon, “Piano Prose” in New York Native, 14–27 February 1983, p. 44.

2. Charles Ives, “Essays Before a Sonata” in Essays Before a Sonata, The Majority, and Other Writings. Howard Boatwright, ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 1961, p. 47.

3. The naturalness of this effect – indeed, of the whole conceit of combining piano and electronics – comes in part from the power of the piano playing: It has to be giving off sparks! This feeling in turn sparks a very interesting idea, one suggested by the recurring ‘wind-chime’ aesthetic mentioned earlier. Tyranny may be using computer music in The Intermediary to realize not just a philosophic attitude toward his piano playing, but his own physical, aural experience. I really wouldn’t be surprised to discover that, like Glenn Branca, Tyranny actually hears unique acoustical phenomena when he plays (and even when he isn’t playing). Wouldn’t it be kind of odd for him to create for us a physical experience he himself has never had? (As long as I’m riding this hobbyhorse, let me just add that the section of pure electronics which interrupts the piano on Side Two, in both its densities and its solo, alarm-like voices, is more than a kissing cousin to certain pleromas of Branca’s Symphony No. 3. And if you’ve heard any of Tyranny’s piano-and-tape performances of The More He Sings, The More He Cries, The Better He Feels, you know that he can work up a fiendish appetite for his own brand of hallucinatory loudness and density.)

4. Tyranny’s program notes to his 20–21 January 1983 performances at NYC’s Marymount Manhattan Theater.

Links to:

SONIC TRANSPORTS: “Blue” Gene Tyranny Contents

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Contents

For more on “Blue” Gene Tyranny, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music Book: Soundpieces 2: Interviews with American Composers

Music Essay: You Can Always Go Downtown

Music Essay: 88 Keys to Freedom: Segues Through the History of American Piano Music by “Blue” Gene Tyranny

Music Lecture: “Intense Purity of Feeling”: Béla Bartók and American Music

Music: KALW Radio Show #1, A Few of My Favorite Things…

Music: SFCR Radio Show #6, Postmodernism, part 3: Three Contemporary Masters

More Cool Sites To Visit! – Music

And be sure to read David Bernabo’s book Just for the Record: Conversations with and about “Blue” Gene Tyranny