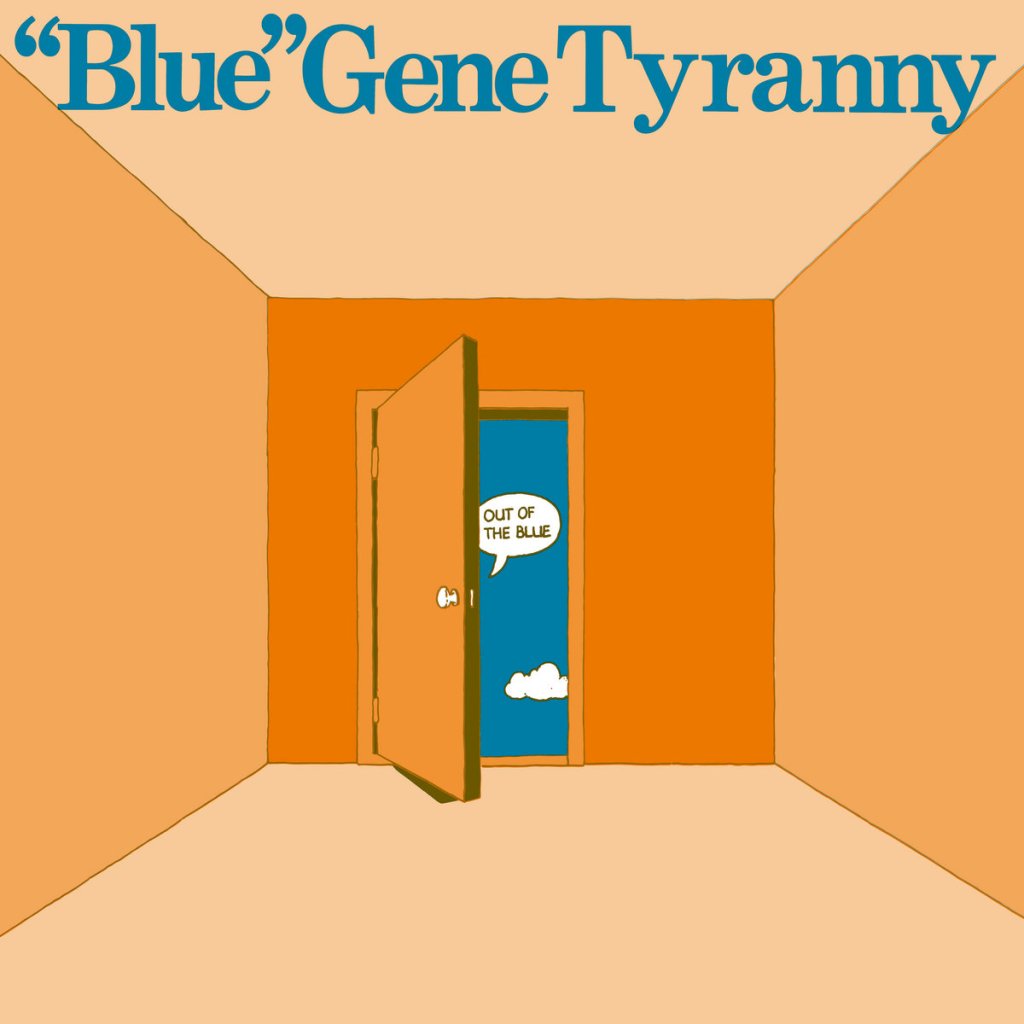

Out of the Blue

The music of Out of the Blue (1976), like that of Harvey Milk (Portrait) and The Intermediary, re-scans a moment of inspired expression: “a letter from home about sound and consciousness,” as the piece is subtitled.[1] Tyranny seemed a trifle apologetic when he admitted to me that he was the actual author of the letter (which specifically addresses him, as in “Dear ‘Blue’ Gene,” etc.). Perhaps he feels somewhat disappointed that, unlike those later pieces, Out of the Blue wasn’t generated from a for-real found object. But hey, let’s look at the record: Besides being literally out of the “Blue,” the letter is legitimately from home, because Tyranny carries home around with him. Besides, the letter certainly doesn’t sound ersatz when you’re hearing this piece. The way you hear the letter, even more than the charmingly complicated text itself, makes it pass for the real thing: The constant background of traffic noises behind the narration of the letter identifies it as one more piece of daily life being picked up by the tape. More importantly, Tyranny selected Kathy Morton to read the letter, and her voice glows with warmth and intimacy – she’s persuasively a friend speaking to a friend. But she’s also Blue’s nameless Narrator, speaking with the deliberate cadences of a person reading aloud. For all her immediacy, this Narrator seems somewhat remote, a one-way presence that sends but doesn’t receive.

That’s how she comes off at first, anyway. Tyranny complicates the question of who’s hearing whom by alternating her narration with songs from two female vocalists. Dubbed “the Versifying Chorus,” these women are “singing the emotions (inside) of objective words (outside),” according to Tyranny. They rhapsodize on the Narrator’s images and ideas, initially drawing their lyrics from words she’s already spoken. But before long they’re anticipating her: They sing of “sunlight in front of your eyes, sunlight inside” before the Narrator becomes bicameral-minded and speaks of ancient prophets who received visions “from one side of the brain to the other; from invisible heaven to foggy earth. This was sunlight inside and outside.” Later, when the Narrator admits wanting a vision beyond consciousness, you recognize the phrase from an earlier choral passage. After a while, it starts to seem like she’s the rhapsodist, un(?)consciously responding to other energies and ideas. And when Tyranny soaringly superimposes them in the penultimate narrated passage, you realized that it’s no longer a question of causality – they’re all in this together, and we’re in the middle of it.

The momentary convergence of Narrator and Chorus has a feeling awfully close to genuine exaltation, with the Versifiers wordlessly hallowing the Narrator’s voice, and then flowering into their own language and ideas. This particular ensemble of soloists almost stops the show; it’s the most passionate and moving music in Out of the Blue. Which is saying a lot, considering how many beautiful passages there are in this piece. But because you tend to focus on the words, most of the instrumental music that accompanies the narrator takes on a subliminal quality; even the strongest moments, such as Peter Gordon’s nifty sax solo, are ultimately absorbed into her character.

Like the computer music of The Intermediary or the electronics generated by Harvey Milk’s speech, the Versifying Chorus is a ‘separate’ energy that interacts with and redefines the main character of the piece. Does that energy just vibrate sympathetically to an independent phenomenon? Does it dictate the letter? Copy it down? “Three guesses,” the Narrator suggests, “a coincidence, a connection outside, a connection inside.”

Actually, the answer is D) None Of The Above: “We’re not attached or separate in space.”[2] If you put a bucket on the ocean floor, is the water inside the bucket attached to or separate from the water outside the bucket? There are other choices besides ordering chaos, folks. Out of the Blue points toward an alternative state of immediate access among all components, “without connections, beyond contradictions,” as the Narrator says – a perspective freed from the desire for continuity of consciousness, and its attendant divisive divisiveness and prejudices.

This idea is related to the sound of a train, which is heard at the beginning and near the end of the piece. Tyranny uses the train to bring the Doppler effect into Out of the Blue: Each time it roars past, its horn drops in pitch. That horn is another sublime contradiction, an unchanging sound that, as it moves through space and time, changes in volume, duration, and pitch.[3] At first, the Narrator associates the train with attachment (“It reminds me of you”) and with separation (“The day before you left on that midnight train”). But the real significance of this sound in motion is its correspondence to the movement of consciousness – “as a metaphor and also as an analog, by sharing the same physical or dynamical shape,” as Tyranny once told me. Or as he once told the Narrator (according to her letter), “a child growing up, the growth of the feeling of being inside yourself, and a sound changing over space and time were similar experiences. Their emotions had the same shape. Oh boy!” Those three movements are all different ways of describing one event: the realization (oh boy!) of consciousness.

They’re also variations on the theme of communication partially obscured – an idea embodied by the Narrator, because the torrent of information in her letter is sometimes more confusing than enlightening.[4] No text accompanies the album; Tyranny wants you only to hear it, in part so you will be somewhat confused by it. (He also injects a little obscurity into the Versifying Chorus, letting them slip into unintelligibility from time to time.) You have to fend for yourself, and grasp her ideas through your hearing and memory, just as you’d do with any person who was speaking to you.

Of course, communication that’s partially obscured is also communication that’s gradually clarifying – which is only another way of describing the realization of consciousness. “I remember Bob [Ashley] once said not to be worried when you are feeling confused, it means you are learning something.”[5] Worrying only makes it tougher for you to recognize that “discontinuity is not broken linear continuity, but a potential single character waiting to unfold in time.” Out of the Blue doesn’t require that you catch every word or perceive logical sequence in the letter’s procession of ideas. If you remain open to all its characters, vocal and instrumental, the piece becomes increasingly clear. Revelation is the basic theme, the constant evocation of both the letter and Out of the Blue: “From time to time I feel another world growing up among the one I experience every day,” says the Narrator, and the music lets you glimpse this world that’s opening to her. But Tyranny isn’t suggesting that the passages for the Versifying Chorus, or the flow of music that hugs almost all the narration, are that world. That world isn’t a place at all; it’s an attitude, a perspective, which Out of the Blue describes through its interaction of Narrator, Chorus, and music.

Within Blue’s instrumental music, there is yet another self-referential character. After all, the Narrator’s letter is being sent to someone, right? And her invocation is intensified by the Chorus, who also addressed Tyranny and call him by name from time to time. That much attention just naturally flows both ways, and so some of these appeals are entered by a rapping, crackling electronic sound, like someone’s fingers drumming a mic. It heard only a few times in the piece, first appearing after the Chorus asks, “Hey ‘Blue’ Gene, leavin’ circumstance? Do you, do you remember?” Its final appearance is after the Narrator’s last words, “Write soon”: beginning tentatively, then growing more insistent and dense, almost singing, until it thins, fades down, and disappears.

The Narrator and Chorus never behave as though they’re hearing that sound – but then, they never behave as though they’re hearing each other, and there’s plainly some kind of meaningful dialogue occurring between them. Tyranny sat right down and wrote himself a letter, so why shouldn’t he answer it too? But answering how, saying what? And to whom? That ambiguous rapping points again to the image of communication not fully revealed, an idea that’s very resonant for Tyranny. (The man actually cast himself as it, you don’t get much more resonated than that.) Recently, he’s been developing a piece that involves recordings of spirit voices from ghost towns. What’s that sound? Who’s out there? What are you trying to say? Are there ways in which I’m hearing you even when I’m not conscious that I’m hearing you? When Bob Sheff was a boy, he’d get in trouble with his parents for sneaking a radio into his bed and staying up at night, listening. Who are those people on those records that that faceless DJ plays, and why are they so excited to be wherever it is they are?

The crackling sound is actually a classic piece of Tyranny begin-again music, created “by a voltage-controlled gate where the Narrator’s voice was the program input and the Chorus was the control (or maybe the other way around, I forget).” Out of the Blue’s mysterious stranger is both an independent character that interacts with Narrator and Chorus, and a musical image which suggests “that they are breaking into each other’s world, perhaps (poetically or really) as apparitions.”

And it’s only one of the many magical electronic effects that Tyranny has stitched throughout the piece. There are quiet falling glissandi, like distant fireworks, in the background of several of the choral sections (most perceptibly in the first and fourth). They’re also present during the interlude for polymoog bass, and that line is a beaut – a balletic hippo straight out of Fantasia. Skeins of synthesizer tones, knotty and imploding, are woven into the piece at various moments; this music makes two major statements, each time sandwiched in between the Dopplering train and the voice of the Narrator. Its last, most elaborate appearance is Tyranny playing a keyboard run that’s also being fed through a delay. On the record, you hear the two lines backwards, so the delay is preceding his actual playing – a musical redefinition of cause and effect, in keeping with the relationship of narrator and chorus. Both its sound and its integration into the rest of the music look directly ahead to the electronics of The Intermediary.

In a paradox typical of Out of the Blue – and of Tyranny himself – the work’s most intriguing electronic gesture is also its most ordinary sound: a humble hum that’s heard throughout the entire piece. Well, almost the entire piece – Tyranny opens with the approaching train, and then brings up the hum. This quiet, high-registered octave on G tints the train, taking you a step back from its literalness. It creates an air of expectancy and wonder, and at first seems to be some special annunciation. Yet it keeps sounding past the Doppler effect and on into the narration, until you stop noticing it. It’s a constant yet largely invisible presence, usually obscured by the other strands of sound. But you spot it every now and then when the textures thin, and it sounds as rich and promising as it did in the opening. The hum never loses its specialness. If anything, it grows more mysterious over the course of the piece. In the final narrated segment, all the background instruments are silent; there is only the Narrator’s voice and the hum. Here again it distances reality, this time with an almost sentimental effect: a cameo of a young woman reading a letter. But that distancing also embraces and affirms this person whose feeling of being inside herself is growing, just as it embraced and affirmed the train and its sound that changed over space and time.

The hum finally gets its chance to shine after the Narrator signs off. A solo by the mysterious stranger is the last rhapsody in Blue (sorry), and in following the diminuendo of that someone faintly rapping, rapping away into silence, you’re left completely wide eared for the hum. Here at last you can begin to savor its character, the subtle shifting of pitch in its vibrato, until it too finally embraces silence.

FOOTNOTES

1. A more formalized, procedural version of Out of the Blue is Tyranny’s 1986 cantata A Letter from Home (Part 1 of Out Beyond the Last Divide). It separates the strands of ideas in Blue’s letter into three kinds of histories: personal, sub-atomic, and social.

2. Tyranny has another woman sing the same line elsewhere on the album, in the song “The Next Time Might Be Your Time.”

3. Timbre too: The changes in pitch and volume automatically entail changes in timbre.

4. “Contradictions are distributed purposefully throughout the text,” says Tyranny, “as evokers that stimulate more intense consciousness, or at least a change of state of mind.”

5. “Blue” Gene Tyranny, “The Roots and the Shoots” (unpublished manuscript).

Links to:

SONIC TRANSPORTS: “Blue” Gene Tyranny Essay, part 9

SONIC TRANSPORTS: “Blue” Gene Tyranny Contents

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Contents

For more on “Blue” Gene Tyranny, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music Book: Soundpieces 2: Interviews with American Composers

Music Essay: You Can Always Go Downtown

Music Essay: 88 Keys to Freedom: Segues Through the History of American Piano Music by “Blue” Gene Tyranny

Music Lecture: “Intense Purity of Feeling”: Béla Bartók and American Music

Music: KALW Radio Show #1, A Few of My Favorite Things…

Music: SFCR Radio Show #6, Postmodernism, part 3: Three Contemporary Masters

More Cool Sites To Visit! – Music

And be sure to read David Bernabo’s book Just for the Record: Conversations with and about “Blue” Gene Tyranny