Skeleton Crew

As the name implies, Skeleton Crew is a small number of people doing a lot of work. Originally, it was Frith singing and playing guitar, bass, and violin; Tom Cora on bass and cello; and Dave Newhouse on reeds and keyboards. And all three on percussion – Skeleton Crew evolved not just from Frith’s desire to sing, but also from his interest in splitting the drum kit between two or more people. This trio of one-man bands meshed together into one drummer, usually by playing percussion with their feet while performing on other instruments. Newhouse dropped out after a few months to pursue other commitments, but Frith and Cora rearranged the sets and began to do the job themselves. Now they really had to live up to the band’s name, which wasn’t easy. I was pretty disappointed by their first NYC outing as a duo and felt they had bitten off more than they could chew. Which was exactly the case, only I didn’t realize then that that was the good news.

In touring Canada and the U.S., they quickly got Skeleton Crew up to snuff, and then well past snuff, into one of the hottest and most imaginative rock acts I’ve ever heard. Their sets were even more virtuosic now that the band was a duo: At their busiest, you could have Frith playing the guitar, Cora on cello, and both men singing and kicking out percussion, all in the tricky meters and cross-rhythms typical of Frith’s music – and sometimes playing against weird tapes with their own peculiar tempi. And just so things wouldn’t get too easy, they’d pause only two or three times in their circa 50-minute sets. Rather than stop after every song, they’d make segues as smooth and strange as anything on Gravity, bringing onstage the heterogeneity and scale of a studio recording (thus giving new meaning to the term “live album”).

Their sets stitched together folk music, fake music, noise, political songs, taped events, even some improvisation. This omnivorousness always kept the audience on its toes: Who could tell what you’d be hearing from one number to the next? But the reason why people would be so enthusiastic at a Skeleton Crew set – there’d be real cheering – was as much for Frith and Cora’s limitations as for their amazing technique. The duo’s performances had the exhilarating suspense ordinarily reserved for jugglers or aerialists: How long can they play without stopping tonight? Can they make that segue without taking a spill? Had they wanted to, the pair could have simply polished and repeated the same set until they could do it without a hitch, but that would have bored them shitless. Instead, they kept developing the material and trying out different things, spinning more plates on more sticks, seeing to it that “everything is almost always on the verge of total collapse,” as Fritz says.[1] Which is just the way he likes it – letting Skeleton Crew tempt fate is one more way he can perform while he’s in over his head.

But fate, like Oscar Wilde, can resist anything except temptation, and many Skeleton Crew sets have simply disintegrated at one point or another. Like all high rollers, Frith and Cora can gamble because they can also face up to losing. Yet part of the magic of Skeleton Crew is how gamely the audience places its bets, with an openness inspired by the musicians’ attitude. That’s why even a technically deficient set could still be received with such relish. I remember one evening when everything went wrong, the music stumbling along in a daisy chain of missed cues, broken strings, and malfunctioning machines. But Frith and Cora strove so mightily and met catastrophes with such humor and grace, that the audience – a large one, with many people who’d never heard them before – wouldn’t let them go. So the pair returned for an encore, and as Cora walked out he accidentally knocked over his cello. That got a big laugh, especially from Frith, who then got stung when he grabbed the mic and it sprang free of its stand. “Well, as long as the roof hasn’t caved in, we’re going to try one more number,” he said and just as he was about to play his guitar, the shoulder strap broke.

Like everyone who followed Frith and Cora’s performances, I was bowled over by how their music kept growing, how ambitious and lively every set would be. But I also found myself getting antsy over a deficiency that wasn’t going away, namely the conservatism of Frith’s vocals. (Cora would sing as basically a backup for Frith.) It took Frith a long time to get around to singing again, and I’m really glad he’s back at it, but with Skeleton Crew, he’d use only a fraction of the vocal techniques he’d developed in his improvisations or with Massacre. His singing would always be subordinated to the songs’ messages, and so a certain repetitiveness began creeping into the sets – a replay of The Art Bears’ problem, only worse, because Frith is no Dagmar Krause. He wanted to make sure he didn’t obfuscate the political punchlines, but if anything was undercutting the impact of the songs, it was their lack of vocal color. The different lyrical personae would get all mushed together, and what I was hearing wasn’t so much the words as the songs’ overall tone of complaining. Granted, that’s something of a relief compared to the standard Bears/Cow postures, Righteous Indignation and Prophetic Utterance. But after a while, kvetching can become the least interesting of the three.

Frith says that singing is for him essentially a live event, “an absolutely direct connection from you to an audience.” With Skeleton Crew, he seems to feel that this connection outweighs the value of using his voice as freely as he uses his other tools. To an extent, his vocal orthodoxy is a holdover from Henry Cow.[2] The band’s group decision-making, with each musician submitting his or her ideas to the scrutiny of the others, was an essential deconditioning experience for Frith. But it also encouraged doctrinaire guidelines of correctness regarding music, lyrics, and the need to make sure everyone gets The Message. For all its strengths, this approach could also tighten the Cow’s ranks into a circle jerk where group prejudices were reinforced and worlds of different materials and ideas were dismissed out of hand.

Paradoxically, Frith’s singing hasn’t caught up with his songs. The Skeleton Crew numbers demonstrate just how much he’s grown – stylistically, intellectually, and expressively – since he left the Cow’s multiple stomach. Of course, they’re political: “You can’t avoid that, whatever you do. If you’ve got beliefs, they tend to come out.” But what hasn’t come out are the rhetorical limitations typical of Henry Cow and The Art Bears. There’s been no Marxist sloganeering so far; in fact, “Los Colitos” finds cold comfort in observing, “Yes, the East is red.” Apoca-lips-smacking is also a low priority. Instead, the songs zero in on the fear of awareness, the refusal to accept responsibility, and the loss of humanity which results. “As long as I’m not there, it’s none of my affair […] Oh no, that’s not my shoes,” Frith sings in “Not My Shoes.” In “It’s Fine,” he mercilessly singsongs, “What we do, we don’t believe. What we don’t do, we believe.” The number then cuts to a harsh, static backdrop, against which he flatly adds a chilling banality: “It’s like that.”[3]

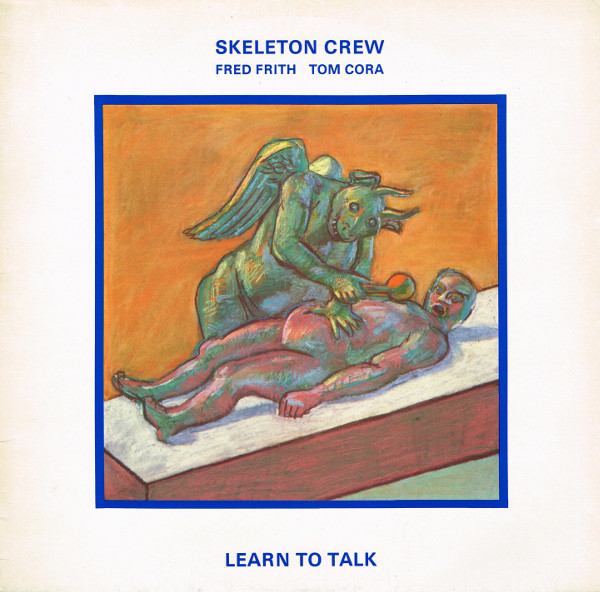

Frith has the imagination, energy, and musicianship to establish himself among the most exciting vocalists working today, but he has to strike consistent balance between style and communicability. I’m sure his innate restlessness and curiosity will jar him out of any impasse in his singing. That liveliness has already prompted some welcome alterations to Skeleton Crew’s sound for their album Learn to Talk (1984). It would have been too easy for Frith and Cora just to set up their forest of equipment in the studio, play a couple of sets, and release the smoothest take. Instead, Learn to Talk is a montage of straight performances and studio alterations, some of which involve manipulating the vocals. The studio’s possibilities are too tempting for Frith to pass up, and so the album explores some effective echoes and double-tracking; timbrally, the most striking flourish is the tiny pinched Frith vocal for “Not My Shoes.” Learn to Talk is still intended to be representative of the band’s sound, and so it doesn’t really go to town in the studio. The arrangements pretty much re-create their live sets, which means you hear a lot of wonderful playing – the guitar-cello duo of “Que Viva” may be the standout. Yet the album isn’t all that representative of Skeleton Crew’s exuberance and fun. The emphasis is on the grimmer of their songs, and the overall effect, both lyrically and vocally, can be rather strident. (Thank goodness they included Cora’s delightful, ever fresh instrumental “Zach’s Flag”!)

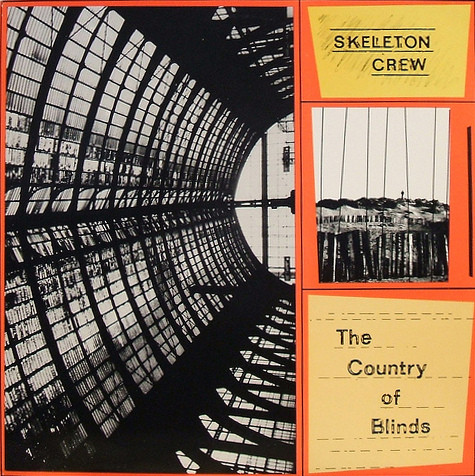

An even more welcome alteration to Skeleton Crew’s sound came in 1985, when Zeena Parkins (electric harp, keyboard, vocals, and of course percussion) joined the band. Her participation has marked a real breakthrough for the Crew, even though she does reduce some of the band’s risk factor: As a trio, it’s much easier for them to keep the music going without a break. (And alas, now that that challenge has been lessened, they seem to find the effort less interesting.) But the good news is that there’s a lot more things going on. So even though Frith has yet to bring home the bacon with his singing, the Skeleton Crew sets now enjoy a wider vocal range, thanks to Parkins’ backups and Cora’s impressive growth as a singer. Yet for all the surprises of their trio performances, I still didn’t expect the wild excitement of Cora’s high-speed melodrama intro for the opening (and title) cut of their second album, The Country of Blinds (1986). Even juicier is the band’s harsh, vicious ensemble singing in “Blinds,” where they dig into some of the punk ferocity that loosened Frith up to begin singing again.

The treatment of vocals is actually one of the great successes of The Country of Blinds. The album is a triumph just for “The Hand that Bites,” from its opening fragmented lyrics to the inspired double-tracking and mixing of its voices, where all the pathos of Frith’s frightened desperate lyrics are made hideously real. And then there’s the three whispering singers that overlay both melodies of “Dead Sheep”; the prestissimo “Man or Monkey,” with each singer trying to outrace the others; the crazy vocal montage that’s abruptly grafted onto the end of “The Border”…

Tim Hodgkinson produced The Country of Blinds, and he’s clearly brought to Skeleton Crew a range and intensity beyond anything I’ve heard them do. “The Birds of Japan,” usually for me one of the less interesting numbers in their sets, is one of the album’s best songs, with all the enigmatic ominousness of Frith’s lyrics, and a climactic grandeur I’ve never heard in it live. “The Border” reaches a metallic, abattoir shrillness that’s absolutely amazing; the effect is terrific and terrifying at the same time. “Bingo” is spectacularly invigorated by abrupt juxtapositions of different chunks of playing, cutting to sections where a wild violin accompanies soaring, wordless vocals. In that song, Frith skillfully suggests the searing frustration under the get-used-to-it coolness of his “Did you play Lotto today? / Did you remember to kneel down and pray? / Maybe it’ll happen to me / […] everybody waiting for another life.” But the knockout is when the song gets swallowed up in an ever-more desperate instrumental din, and then gives way to an ecstatic folk dance on Frith’s violin. (The man just can’t hold a grudge.) “Bingo” isn’t just the album’s tour de force, it’s one of the high moments in all of Frith’s music.

At this point, it looks like Skeleton Crew is going to stand as the best band Frith has worked with. His own talents have developed far beyond his days with Henry Cow and The Art Bears; and the Crew has a potential for growth which completely distances the restricted experiment of Massacre. That potential, which Skeleton Crew keeps expanding, makes their sets and albums so unique – Frith hasn’t hired talented young musicians to work for him; in Skeleton Crew, he’s built a kind of collaborative gymnasium where everybody has to work at learning things they’ve never tried before. At virtually every set, you can hear how one more limitation has been exploded, one more barrier breached. It’s very encouraging for the band’s continued popularity and success – and for anyone trying to realize his or her own resources of energy, daring, and imagination.

FOOTNOTES

1. Ted Greenwald, “Attack of the Killer Guitars – Fred Frith” in New York Talk, June 1984, p. 18.

2. It also has its roots, I suspect in his pre-Cow days as a folk singer. His Skeleton Crew songs are a new way for him to recapture that intimate (and political) communication he used to share with audiences.

3. It was effective at certain live performances, when he eloquently underplayed it; on Learn to Talk, he hams it up into banality.

4. But couldn’t he have played reeds on at least one cut? Other than that, The Country of Blinds only major sin of omission is the absence of Skeleton Crew’s fantastic violin-and-two-accordions instrumental, which refracts Jelly Roll Morton through a Bulgarian dance band.

Links to:

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Fred Frith Essay, part 10

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Fred Frith Contents

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Contents

For more on Fred Frith, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music: KALW Radio Show #1, A Few of My Favorite Things…

Music: SFCR Radio Show #6, Postmodernism, part 3: Three Contemporary Masters