Q: Is it true you’re entirely self-taught as a guitarist?

Frith: As a guitarist, yes. If I were to be strictly honest, then I’d have to say that I did once have two lessons on classical guitar. But by that time I’d been playing guitar for a couple of years, and as far as I was concerned – as an arrogant 15-year-old – the lessons were too much behind the stage I was already at with my left hand. I got bored very quickly, so I dropped them. I was learning things, classical techniques, with the right hand, but the left-hand stuff consisted of things that I didn’t even want to think about. So I did that for only a couple of weeks.

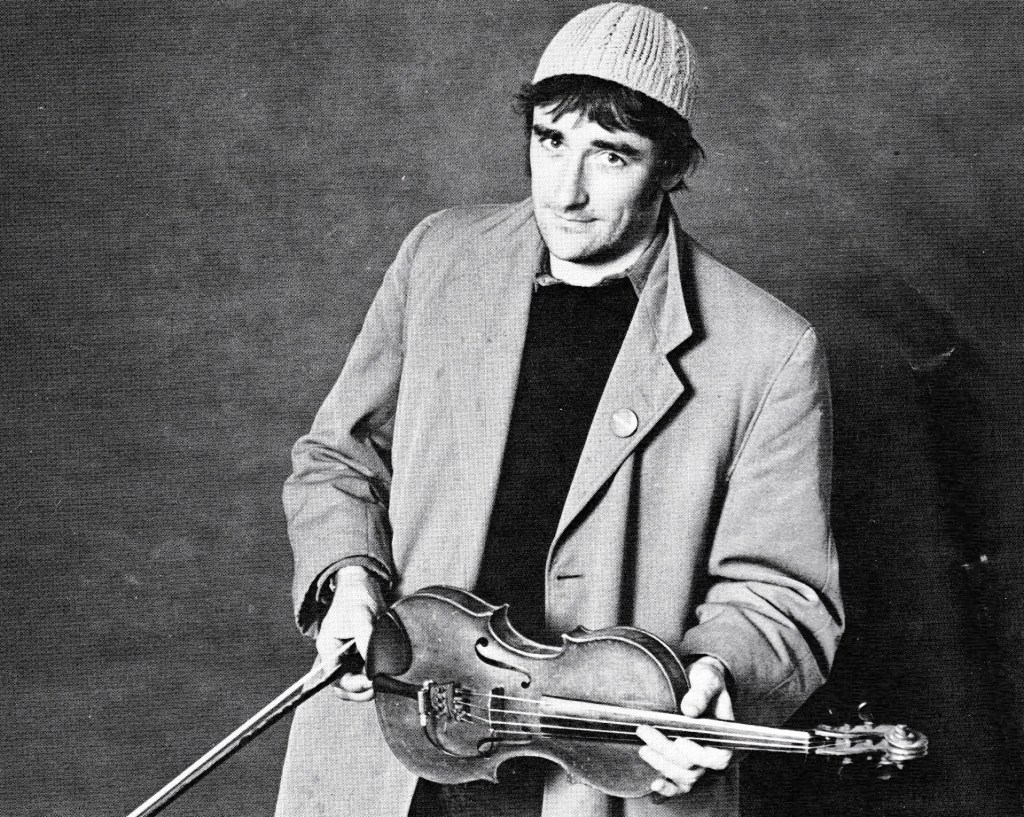

Q: Then what formal musical training did you have? Was it only on violin?

Frith: I started learning violin at the age of five. I think that the first teacher I had was quite experimental; I seem to remember that I hardly ever touched a violin at all for the first year of the lessons. Instead, I learned a lot about how to relax my arms and fingers – which was actually very useful, I think.

There were times when I’d really enjoy playing the violin, and times when I wouldn’t. Eventually, I got a teacher whom I really disliked. That coincided with my being 14 and finding a guitar lying around, so I took up the guitar instead. I continued to play the violin, but I didn’t have lessons anymore, and I lost a lot of technique in the ensuing five or six years. About half way through Henry Cow, I realized how much I had lost, particularly bowing technique.

Q: You learned keyboards by yourself?

Frith: Yes. My father plays piano very well, and there was always a piano in the house. I was always fooling around on the piano – I can never remember a time when I wasn’t. I taught myself to play a few simple classical pieces because that’s what my oldest brother was doing, and I wanted to see if I could do it too. He pretty soon left me behind both on the piano and the violin, though – in fact, he’s still a very active amateur musician.

Piano playing started in earnest for me when I began playing the blues, because it seemed a lot easier! I guess that was because technical skill, in the terms that I’d probably understood it, could be made entirely subservient to emotional expressiveness – which hadn’t been the case with anything I’d ever heard before. This realization, and the discovery that an instrument – not the piano so much, but the guitar or the saxophone – could sound like a human voice, could effectively be a human voice, had a profound effect on me. This was when I started a band in school. Originally, the band I was in played Shadows numbers. But after hearing the late great Alexis Korner, I started listening to everything I could find, and playing blues piano and blues guitar and blues everything else! I worshipped Little Walter, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, and Muddy Waters, of course, but also Ray Charles and Snooks Eaglin. In fact, for a short time I sang and played harmonica in a blues band – didn’t play guitar at all!

Q: You never studied composition or theory?

Frith: When I was about 12, I did formally learn some rudiments of music. It was for only about two or three weeks. Some of it I knew already, and the rest of it was over my head, so I really didn’t get much from it.

Q: Was it working with other musicians that really taught you about music? Did they get as much from you as you got from them?

Frith: The great thing about working in bands for me has always been the collectivity of the creative work. In this regard, Henry Cow was certainly the formative educational experience of my life to date. We were all teaching each other things all the time, musical and otherwise. Early on in that experience, I probably knew more about music theory in a crass, general kind of way, than the others did. But by the time we broke up, I felt like a musical poor relation.

Lindsay Cooper, for example, had had an almost complete academic training in music. She could have gone on to become an orchestral musician (which she very sensibly refused to do). She has a far greater knowledge of musical theory than I have, and she brought a different kind of sensibility to the group. She was more of an instrumental perfectionist than I was, I think, and she wouldn’t settle for something in her bassoon playing that wasn’t up to her own standards. Tim Hodgkinson has the kind of quiet, concentrated dedication which could closet him in a room, composing or practicing or studying, for weeks and weeks, with remarkable results. Chris Cutler was possessed of that rare imagination which is always a couple of skips ahead of the technical capacity to realize it – infinitely preferable to the other way around, which is more normal. This is the source of much of the delicate tension in his drumming, the quality of striving. And Dagmar Krause had the capacity to lift the whole group, and to really grab an audience. John Greaves was very intense. I learned a lot from all of them.

Q: Would it be correct to say that Henry Cow was attempting to synthesize methods from jazz, rock, and modern concert music?

Frith: Definitely not! I think it would be a mistake to see us as more conscious than we were. In certain respects, I think we were almost too conscious, but that was with the non-musical things we were trying to do. We had a conscious idea of what we were doing in terms of, say, our relationship with the music business, and self-organization, and solidarity with other like-minded musicians, and those kinds of things. But in musical terms, I don’t think we ever formulated any kind of practical philosophy at all, though we issued a lot of grandiose press releases. Our general work method was quite intuitive and pragmatic. It also depended on different people’s different ideas about what they were composing, which then could get altered in the context of the group in rehearsals.

I know, for example, that if you had said that about jazz to Chris Cutler at the time, he would have been horrified. Tim, on the other hand, learned music initially from a jazz context; he came to music through listening to Charlie Parker, Coltrane, and Ornette Coleman, as I recall. I was the more eclectic member of the group, inasmuch as I’d been a violinist in school orchestras, played and sung in pop groups and blues bands since I was 14, and was also involved in folk music and free improvisation at the time the group started. Lindsay of course had her academic classical background, though she’d also played in a rock group and done improvisation quite extensively. John Greaves had played in his father’s dance band. So it’s true that, as individuals, we were all coming from different environments, but I don’t think it had a conscious effect on what we were creating as a group, though you can’t underestimate the effect it would have on our subconscious.

I think you’ll find that a lot of musicians don’t spend much time thinking about how what they’re doing fits into one category or another, whether it’s a synthesis or not. Those are the kinds of things that preoccupy journalists. Of course, we discussed music, and Chris and Tim especially had articulate theories about it. But what it came down to in the end was finding new life and strength and whatever basic forms we worked in, whether it was free improvisation, songs, scored pieces, or whatever.

Q: Is this true of The Art Bears as well?

Frith: There are important differences between The Art Bears and Henry Cow. First of all, The Art Bears is not a group in the same sense, and therefore isn’t informed by the same criteria as Henry Cow. Henry Cow was a long-term commitment by a lot of people who were working on it absolutely full time, all the time: If it wasn’t the music and the rehearsals and the concerts and the recordings, then it would be the administration, trying to find money and new vehicles and equipment, keeping a team of road managers, organizing tours, planning ahead, all that stuff. We really didn’t think about very much else for the whole time that Henry Cow was in existence. Whereas The Art Bears was never a group like that. We just went into the studio a few times, basically.

The Art Bears happened when we went into the studio to make a Henry Cow record. It’s a strange, convoluted story. Dagmar Krause had left Henry Cow a year or two years previously, and there was a piece that we had performed when she was still in the group, which we wanted to record. About a week or two before we were supposed to leave to go into the studio in Switzerland, we completely disagreed about the lyrics of the piece. It was a piece of Tim’s: a big massive work that would have taken up a side of an album, probably more. We had a serious disagreement about the content and quality of the lyrics and tried to work on them together – which was disastrous. We had about two days to go, and Dagmar had been invited to come with us. She dropped other things to do it, so we felt obliged to do something with her, even though we couldn’t agree about it. So we decided that we would try to write as many songs as possible, which was a pretty new departure for Henry Cow because we tended not to do songs. We’d done some, but not many. We went to Switzerland to do a few gigs, and while we were on the road, we started writing songs. The energy was mostly coming from Chris and me because we were the main disagreers about Tim’s peace. We felt that it was incumbent upon us to come up with replacement material.

So Chris was madly writing lyrics, and I was madly writing music. Tim and Lindsay worked too, of course, but most of the new stuff was Chris’ and mine. We got into the studio and recorded all this material that we didn’t even know, things that were written two days previously. At the end, we couldn’t agree about the quality of the music that we’d just made. Half the group didn’t want to put it out at all, or at least not at once and not without big changes – partly, no doubt, because of the whole history of the reason we’d done it, and the fact that we had intended to do something else, which we hadn’t done (although obviously there were other reasons). In the end, it was agreed that we’d put out this record under a different name instead, and that Henry Cow would make another record at another time. We removed a couple of tracks and added three new ones to cement its new identity. So the first Art Bears record, Hopes and Fears, was born as a Henry Cow record, but it became an Art Bears record as a gesture of compromise on the one hand, and a new beginning on the other. Then, a few months later, Henry Cow made Western Culture, which didn’t contain Tim’s long piece either, but which did have Lindsay’s first recorded composition at long last, and also a lot of new material by Tim.

Chris, Dagmar and I liked the Art Bears record a lot, and we decided that we wanted to pursue that, so we went into the studio at another time and made Winter Songs. We recorded again in the summer of 1980 and made The World as It Is Today.

Q: Were you losing interest in making music with Henry Cow by the time of Western Culture?

Frith: Western Culture was made after a six-month period of touring, and during that time we already knew that we would be breaking up at the end of it. That was a pretty weird time. We had made the decision to break up shortly after doing what became the Art Bears record, but we were committed at that time to six months on the road. It might have been more sensible just to cancel everything, but we felt that we should use the period constructively and write a whole lot of new music, rather than just play the same pieces we’d been doing before: a symbol of the fact that the whole time that we were together, we would be committed to going forward; that it wasn’t really a question of Henry Cow just breaking up and disappearing. We actually wrote new music for all those tours; we weren’t performing very much that we had done before. I think there was a big feeling that no one really knew why we were breaking up by the time we actually did.

Q: No one within the band?

Frith: Yes. It became quite tense. On the one hand, we knew we were breaking up, and so people were gradually withdrawing into themselves in order to avoid the close contact with each other that being in a group is all about. And on the other hand, we were actually still a group that was working together. So there was a big tension. This was in mid-‘78. Western Culture was recorded in August of ‘78, and that was the last thing we did together. We left the studio and that was it.

Q: It’s been said that Henry Cow had a limited popularity because the music was too difficult. Do you think there’s any validity to that?

Frith: I think it’s bullshit, but I’m biased! I wouldn’t want to pretend that some of our music wasn’t difficult, because it was. But “difficulty” means different things to different people. Obviously, we never tried to make hit singles or anything. I like the idea of an audience having to do some work when they listen to music. I don’t think listening to music should just be passive reception. It can be something where you’re actually engaged in what’s going on. In fact, if we did ever have a philosophy, that was probably close to the heart of it. We were ourselves engaged in what we were doing, in terms of trying to do things that we couldn’t do, as well as trying to do something in the medium of rock music, which was demonstrably independent of the practicing norm as to what form or forms rock music should take. We were utterly disinterested in any commercial consideration. We wanted to make vital and original statements that worked on more than one level, and which would force a strong reaction from the listener, one way or another. And clearly, as time went on, we wanted to bring our political beliefs into the music itself. Anything was better than the bland hypnosis that was coming out of the radiowaves. We expected and anticipated that people would have to make an effort themselves in order to get anything out of what we were doing. So if that’s what you call difficult, then we were sometimes difficult. But not “too difficult”! I can be categorical about that because I seldom do a gig anywhere in the world, from Japan to Texas to Czechoslovakia, without being accosted by Henry Cow fans, some of whom weren’t even born when we began.

Q: Why was it that Henry Cow didn’t have the larger audience? Were a lot of pieces too long for commercial airplay?

Frith: No. In Europe, airplay is much less significant than it is in America. The major difference between the dissemination of rock music in the ‘70s here and in Europe was that here, radio was absolutely crucial – you couldn’t sell records without radio. In England radio is important, but there’s a lot less of it. Therefore, it’s much more critical that you get good notices in the weekly music press. There are three weekly magazines, and they’re more or less organs of the industry in England, inasmuch as they’re full of recording-company advertising. They’re dependent for their survival on that advertising, not so much on their circulation. The record companies in turn depend completely on them to give out the right kind of information about their artists. The journalists can kid themselves all they like that what they’re doing is independent of the record companies, but when it comes to the crunch, as it does from time to time, then things become pretty clear. If New Musical Express writes a series of bad reviews of Island Records’ artists, Island can threaten to withdraw their advertising for three or four months. It’s very clear that there’s a certain point beyond which you’re not allowed to go.

So with Henry cow, it was more critical what journalists were saying about us – the opportunities for airplay were virtually nil – and we never had any real luck with major journalists in any country in Europe. There were always people who were wildly enthusiastic about us, but often they would express their enthusiasm in such a way that no one would actually want to listen to us! Steve Lake, with Melody Maker, for example, who liked us a lot and really wanted to help, made us seem boring and academic – “playing difficult worthwhile music.” The journalists tended to latch onto that, that we were playing stuff that nobody would want to hear, but that people should listen to it, out of some bizarre sense of duty. Which just made us seem very unattractive, of course. The kind of people that such writing would attract would come up after a gig and ask me what kind of pedals I was using, all kinds of technical questions. And at the same time, it was quite plain that they really hadn’t listened to anything that we’d done at all. They’d heard it completely on a technical or an intellectual level. Which was depressing. Fortunately, a lot of other people came to concerts unaffected by such matters and seemed to get more out of it. For me, the music meant a lot more, and I wanted people to tell me that they felt it that way too.

Q: In retrospect, are you disappointed with either the history or music of Henry Cow?

Frith: No. It was a very rich experience. There were a lot of things that I regret we never did, there were things that I’m very happy we did; things about the music I detest, things about the music I love. I feel just about everything about Henry Cow. It was a very total experience.

Q: You were talking about the idea of conscious decisions in writing music, and said that Henry Cow worked intuitively. Would you say this about yourself as well? How deliberate were you in approaching the different musical styles for Gravity?

Frith: I still think, on the whole, that I’m pretty intuitive.

You have to keep in mind that intuition is mostly something connected with the actual realization of the music itself, but not necessarily with the process prior to that. It would be wrong to say that Henry Cow was intuitive, as if we didn’t talk about anything at all, or think about it. One thing that I meant by intuitive was that, when we were actually playing the music, we weren’t playing it with our heads. And that’s pretty much the way it is for me now. I did a lot of research for Gravity: a lot of reading, a lot of listening. It took about two years to do that research (although obviously I was doing a lot of other things at the same time). So that’s hardly what I would describe as intuitive. But the actual writing and recording of the music, the way it was put together and produced, didn’t really involve the same kind of consciousness that had gone into thinking about it before I actually started working on it. I don’t think I’m capable of working in that conscious away.

With Gravity, I suppose what I was doing was trying to find a way of writing music that contains the same qualities that you find in certain kinds of ethnic music: that contradiction between a kind of seriousness – or gravity, if you like – in music, and a sense of celebration; the idea of joy being transmitted. Something about Henry Cow’s music that I never really liked was the fact that, even though we spent a lot of our time laughing and making stupid jokes, the music itself had a habit of sounding pompous. In a good performance, that pomposity would be wiped out, the music would really come to life and have exactly the kinds of qualities that I like. But when a performance was going badly, it would tend to become very, very “serious” – in the sense of us withdrawing into ourselves and away from the audience. Maybe that’s the source of the reputation you mentioned earlier.

When Chris first gave me the lyrics for “The Dance,” I started having thoughts about doing a record of dance music from all over. People used to say about Henry Cow that you couldn’t dance to our music, as a little joke. So I thought it would be quite funny to think about dance music, especially because so many cultures have dance music that isn’t in 4/4. The current Western idea of what constitutes dance music is that it should have an enormous beat and be in 4/4. I’d spent time in Greece and listened to people playing dance music in 7 and 9. That’s just the beginning, there’s so much more depth and richness in dance music than most disco DJs ever dream of. In its conception, Gravity was an exploration of that. But it became more than that, of course. If I’d done it four years later, I might have followed the same route as Malcolm McLaren. It’s a curious relationship. As it was, it’s interesting to compare the record to Holger Czukay’s Movies and Eno and Byrne’s Bush of Ghosts, which came out around the same time.

Q: When you entered the studio in recording Gravity, did you always know what you would come out with?

Frith: No, of course not. If I come out with what I expected when I went in, then I’ve usually failed, in my view. Old Frith cliche!

I was once involved with a project for Italian radio. When I got into the studio and started working, it became clear that a lot of the ideas that I’d had beforehand could not be realized in the way that I wanted, due to the situation in the studio and the time available. Therefore, I had a choice: I could make something out of what I had, and try to make the music just as good and strong as possible, or else I could say that it was just not possible to do what I wanted to do, so forget it. Of course, I chose the former, although there is an aspect to this question that I’ve never resolved in my mind. I’ve tended to believe that you do whatever you can and make it as strong as possible, even though an idea that you come up with has nothing particularly to do with what you originally intended. This is partly a question of time and economics: In order to realize an idea from scratch and do it really well, you probably need to fail three or four times before you come up with what you want. I’ve never had the economic luxury of being able to fail in that way, of going back into the studio a month later and trying again. So my mentality has been to follow whatever ideas are working, and what you come out with is what you come out with. Gravity was no exception, although Gravity stays a little too close to its ideas for comfort, sometimes. But a lot of things were completely different from what I had expected. Zamla and The Muffins were even better than I had expected them to be, and they really brought what I had in mind to life.

Q: There are all kinds of unusual sounds on Gravity, some of which I mentioned on the album cover. The Dogs of Rockville and Rain on the Roof are easy to catch on Side Two, but where are Toads, Seals, The Renaissance, etc. on the first side?

Frith: I often have a portable cassette machine when I travel, and I’m always recording things – on the streets of New York, or in the country, or wherever. Rain on the Roof was recorded when I was sleeping in my van in Brussels; it was dripping from the trees onto the van roof. I have a whole lot of recordings of all kinds of stuff, frogs, toads, birds – I’m quite a keen bird watcher, you know. There are sounds of animals and birds from other recordings as well, along with a few fragments of ethnic music that I wanted to use: Bulgarian, Ethiopian, and others. The shout at the end of “Norgarden Nyvla” is from a Native American tribal dance. Most of the things that I used were actually altered in such a way that they’re not recognizable: A lot of the animal and bird sounds that are used are at a different speed from that at which they were originally recorded. The Renaissance is part of a 16th-century dance played by an early-music consort, which is just audible through the clapping that links “Don’t Cry for Me” to “The Hands of the Juggler.” I thought it was quite striking to juxtapose the precision and formality of the consort with the loose feeling and marginal competence of us all clapping in the studio.

Q: I’ve read that you acknowledge John Cage’s book Silence as a musical influence is that accurate?

Frith: That’s accurate. Reading Silence was very important for me. When I read it, I was about 17 and a bit of a blues purist. I was stuck in a mental hospital – not as a patient, but as a nurse – and it was phenomenally boring whenever I wasn’t actually working. I had three days off a week and I lived in this place, so I used to teach myself to play classical guitar or I’d play the blues. There wasn’t much else to do. (I did win a table tennis tournament, I seem to recall!) John Cage’s Silence made me aware of a whole other area of musical thought that I hadn’t considered at all.

Q: Cage has spoken out against improvisation because of its reliance on the performer’s memory and taste. Does this criticism bother you at all?

Frith: Not in the slightest. I can see the relevance of the remark, and I must say – hypocritically enough – that I actually dislike an awful lot of improvisation. Probably more than half of all the improvised performances I hear do nothing for me. Which is no doubt due to the performer’s memory and taste as much as anything else (and my own, of course, as a listener). I certainly think that improvisers have a real problem knowing when to stop.

Someone like Cage is revolving in a world which has to do with the history of Western art music, the “classical tradition.” Musicians that are trained to play that music often have the problem that they’ve invested years of their lives practicing, and so have a vested interest in being able to do something on their instruments which is definitely not called for by people like Cage. A process of de-education is involved, and not many people are prepared to go through that. An academic instrumental training is thoroughly draining in terms of the imagination, as is clear from the conservatism of orchestral musicians the world over.

People seriously involved in the world of free improvisation have built up a whole series of de-educating procedures that are inherent in what they’re doing – actually vital to the music that they’re playing. This would actually be quite compatible with Cage’s philosophy. The trouble is that a lot of people are also coming from a jazz mentality, which has got a different kind of attitude to virtuosity, one that can bug me just as much as the “serious music” one.

I don’t think virtuosity is a bad thing. What’s important is that, in improvisation, one should be able to adapt one’s virtuoso techniques to one’s own language. And, as in any kind of music, the technique is not the reason for the music’s existence. Too many times, technique is seen completely separately from musical use, from what you’re actually trying to play to people. For a lot of people, the idea of technique never goes beyond things like the ability to play incredibly fast and articulately. I find that a lot of music is actually closer in spirit to athletics than it is to musical communication: the idea of competition in conjunction with the mentality which sees technique as “prowess” rather than as a means to an end.

Q: In expressing their reservations about free improvisation, some critics have fixed on its tendency for concluding with a gradual diminuendo on the part of all the musicians. Does that strike you as a serious criticism?

Frith: Sure. Sudden stops are gradual diminuendo. Quite honestly, when I read some of the criticisms, I have to agree. But I think that it’s very easy to seize on certain things in order to put down a whole medium – which is a mistake. Because I still think that the best improvised music is transcendentally wonderful. One of the drawbacks has always been that you have to wade through so much shit to get at the gold. And it’s frustrating that the structures do tend to fall into habitual patterns, especially with people who are not particularly versed in improvisation – they’re the most obvious things that people fall back on. But even people who’ve improvised for years fall into the same old patterns. Maybe it’s a red herring – after all, there are limited numbers of endings for any kind of music. Do you stop dead or do you fade? Is there a resolution or not? What form does it take with reference to musical conventions? Anyway, though knowing how to end well is a difficult skill to acquire, there are plenty of other aspects of improvising. The beginning and the middle, for example!

The other hoary old critical chestnut is the one about it being the kind of music which is much more pleasurable to do than to listen to. I’m sure that’s true in many cases. For a lot of people, the excitement of developing their improvising intuition far supersedes the consciousness they may or may not have about what their music is for or who it’s going to – even where it’s going. But the matter of developing your skill and learning how to work spontaneously is very important and takes time – never ends, actually.

The question really is whether this kind of activity should be encouraged, with the end in view that eventually, something strong will emerge, or whether you merely say, “Well, this is just self-indulgent” and forget about it. I think a lot of critics of improvised musics tend to swing on pendulums: Either it’s wonderful, or all improvised music is theoretically unsound. And because of the way criticism and the media all work, there’s a tendency to dwell on personalities. So stars emerge in the field of improvised music, which is generally counterproductive to the development of music as such, because it means that every time somebody comes along who’s not a star, the critics either don’t go to the performance, or if they do, they measure it up against a bunch of supposed improvising icons. In my experience, all-star improvising groups can be awful – nothing but self-parody or the safeguarding of reputations in crass ways. The biggest problem is probably the fact that listening to improvisation requires a lot more from an audience, a kind of commitment that’s rare. You have to develop new sets of criteria and stop expecting to consume fixed musical products. In an atmosphere that encourages taking chances, the audience grows. Right now, we’re in a backlash, so for the most part people want the security of knowing they’re getting, you know, the goods!

Q: Could you describe some of the techniques you’ve used to prepare the guitar for your improvisations?

Frith: I don’t use any particular thing. I’ll use anything, really. There are certain things that I’ll use more than other things. I’ve developed certain kinds of techniques involving bits of glass or chopsticks or newspaper or string. But fundamentally, I try to get a sound out of anything that comes to hand. People tend to leave things for me at gigs: I find items on the table when I pack up that weren’t there when I started! If I’m in a hardware store, I tend to be looking at stuff with the idea of what I might be able to get out of it from a musical point of view. So the things that I’m using are constantly changing, and the relationship that I have with them is changing too. I might use a chopstick to do one thing, and then at a gig three months later, I’ll hit on something else, and so my relationship to the chopstick will change – I’ll tend to think of it as something else, with another technique to be worked on from that.

Q: How much control do you have over the sounds you produce?

Frith: That varies considerably. I suppose I’d like to be in control. At the same time, I’m well aware that that very intellectual aim is not always going to be realized. Maybe I don’t want to be able to realize what I’m trying to realize! But in terms of my hands, what I’m trying to do is arrive at a point where I can repeat something. In other words, I want to know what I’m going to be able to do with a certain effect. Of course, it never works out that way because I don’t practice these pieces at home; I do them only at concerts, which is part of the philosophy of it.

In any given performance, you can illustrate what’s going on with, say, three different phases. The first phase is when a sound is produced in a certain way. You observe how the sound was produced and try to reproduce it – this is the beginning of learning a technique. Say you dropped something on the strings by mistake, and it makes a sound that you want to reproduce. You have to work out what you dropped, where it fell on the strings, what the settings on the amplifier – were all the different parameters that determined the nature of the sound. Then you might try to reproduce it. The second phase is where you’re working on this technique. In the process of working on it, it will probably be transformed into something else, because once you start being conscious of something, it necessarily changes its character. The third phase is when you actually have a technique that permits you to determine what sound you’re going to produce. You’ve been through these first two phases, and you’ve arrived at a point where you have a resource you can draw on.

In any given concert, there are going to be masses of these things going on all the time, because it’s not a question of just using one technique at a time. There are many, many different techniques that are in different phases – the first or the second or the third – which you’re drawing on all the time that you’re improvising. So there are going to be some techniques that I have where I’m well aware of what I’m capable of doing. The technique is then no longer important as a technique at all. It’s just a vehicle for the sound, the music itself, that’s coming out of the technique. You use that as the basis of what you’re doing because you’re no longer thinking about the technique at all – in performance, you’re not thinking about anything, you’re just playing. The other two phases are happening simultaneously with that. So there’s a dynamic learning relationship that’s going on in the performance between the strugglings with the different levels of technique and the final ability you have to transcend particular techniques altogether.

Q: Have you found in improvising that there are certain hot audience buttons that you can press? Certain gestures or events that will always get the same kind of response?

Frith: It’s funny, I used to think that. I used to think that there were certain things that would always raise a laugh, and certain things that would stop people from laughing. But I’m not at all sure anymore. Some of the things that used to raise a laugh, don’t, and some of the things that used to appear intense now appear very theatrical and make people laugh. Maybe there are subtle changes in the way that I’m doing them myself. It’s hard to say.

Q: It could also have to do with the relative novelty or familiarity of the event itself.

Frith: There’s that element of it. There’s also the element of self-mockery. I tend to poke fun at myself. In performance, after a certain amount of time, I’m very aware that there are certain things that I do, and I start to look at them with an ironic perspective. So the audience perceives the same gesture in a different way, because you’ve changed it by your attitude to it. So maybe something that I could do with absolute conviction three years ago, I would do now by saying, “How could anybody do that with absolute conviction?”

Q: Do you find yourself trying to avoid something that you think is merely a hot button?

Frith: When you get up there and perform, you just do it. I don’t think it ever really happens that I consciously say to myself during a performance, “Oh, this will get ‘em going! Watch out! Wheee!”

It doesn’t work like that. I may do something which elicits a response from an audience, and having become aware of that response, I might use it: either push it further and see how far the response will go, or suddenly remove it to pull the ground from under their feet. It’s done on a very spontaneous level. I think that one’s intuition is developed to such a fine degree that you can go through a very rapid number of processes of thought and feeling when you’re improvising. That’s not the kind of intellectuality you’re implying when you talk about, “Do you press this button or that button?” It’s quite a subtle distinction.

Q: Would you be interested in writing, say, a string quartet?

Frith: I think it would be stupid of me to write a string quartet. I don’t think I could write a string quartet. It seems in a way completely irrelevant. Who’s going to perform it? Who’s going to hear it? Why bother to write a string quartet? It seems a particularly pointless thing for me to do. My training, temperament, and education completely preclude the possibility that I could do anything like that.

I’m more interested in popular music forms. I don’t see Gravity, for example, as having to do with “serious composition” at all; I don’t think of myself as a “serious composer,” you see. I prefer working around my own strange ideas about popular music, than worrying about being a composer writing those kinds of structures.

Q: How did your performing with The Residents come about?

Frith: I first heard a Residents album when I was in Henry Cow. A guy at Virgin Records gave an album to Chris Cutler. Chris in particular was completely knocked out with The Residents. At this time, we had planned for Chris to visit the States to try to set up contacts for a Henry Cow tour. The group then broke up, but he had planned the trip, so he came to the States anyway, for about two weeks, and while he was in California, needless to say, he visited The Residents. That was the first contact we had with them. Subsequently, when I first performed in San Francisco, I visited them also. We have the kind of relationship where, if I happen to be in town, I might end up playing something on whatever they’re working on.

Q: How much freedom do you enjoy when you work with them?

Frith: It’s like working with Eno: in one sense, you have total freedom, and in another sense, you have no freedom at all. While I’m in the studio with The Residents, I can do whatever I want, literally. (This may not be strictly true with Eno.) For the Commercial Album, what they said to me was, “We’ve got these 40 songs, and you can play on any of them where you think it’ll fit.” Then they played each song for me. I’d say, “Yes I’ll play a bass on that,” and so we’d go back and I’d play a bass on it. Or I’d say, “There’s nothing useful that I can add to that,” and we’d go on to the next one. We went through all the stuff they’d recorded at that time – I think they subsequently recorded a few more tracks. I ended up recording on, I suppose, about 25 of the 40. That’s where the freedom is. Afterwards, of course, I went away and they decided which bits they were actually going to use and how they would use them. I talked to one of them later, and he told me that I’m actually on at least 15 of the finished tracks. But I can recognize my playing on only three! Most of the things I did were actually very simple; I don’t have a vested interest in making myself sound either recognizable or complicated. I just wanted to do what was right for the music. But the things that I recognize as my own are all bass parts. I think that I have a very distinctive way of playing the bass. There’s only a limited thing that I can do with it, and I do it in a way which is quite identifiable. I’ve been playing the guitar much longer, and I can do a lot of different things on the guitar, make it sound like a lot of different things. So I end up not being able to distinguish what I do after a month or two.

Q: You mentioned the other name I wanted to drop: Brian Eno.

Frith: I haven’t worked with Eno for years, but when I did it was mostly with a lot of other people, and we’d be experimenting with all kinds of conceptual skeletons. Sometimes he’d have a basic idea and we would work on it together. Other times we’d start from scratch, doing something without a particular idea in the forefront. Then he would take it away, and either it would turn up on a record sometime later, or it wouldn’t turn up on a record at all, or would turn up on a record minus what I did, or would turn up on a record and what I did would be central to it. All the controls concerning the way the music finally sounds are his. When I worked with him, I had problems with that because the only way I’d ever worked in the studio was in a collective way – all my experiences in the studio at that time were with Henry Cow (apart from my guitar-solo records). So it was a little disconcerting to realize that, in the end, I would have no say about what was going to end up being used. No matter what I was playing, or what I thought of the music, in the end he would make all the decisions. Now, having done this myself to a certain extent with Gravity and Speechless, I can recognize that there are certain kinds of music that you couldn’t make any other way. Collective decision-making needs a lot of time and patience and pain to become truly effective.

Q: Recently, you’ve been doing a good deal of singing, both with Skeleton Crew and on Cheap at Half the Price. You’ve broken a long silence in this regard, and I’m curious as to what held you back from singing for so long.

Frith: Well, there are different layers of being held back. I used to sing a lot. I’ve always sung, right from very young – I was a church-choir-type. My early experience as a professional musician, right through high school, was singing in folk clubs, before Henry Cow existed. At university, I had that job where I was the singer in a blues band. I should think it was pretty dreadful, but I enjoyed it, it was a lot of fun. And when Henry Cow began, I wrote songs for the group, and we performed a few of them. Some of them are even unfortunately extant, off radio broadcasts from the early ‘70s. But there was a kind of unspoken agreement, I guess after the first radio broadcast, that my singing was no longer acceptable.

Q: A unanimous agreement?

Frith: I don’t suppose I agreed! But I didn’t have enough super-confidence in my voice to think, you know, “I’m going to sing whether you like it or not.” Because I don’t think I’m a singer even now. I think I have a good way of using my voice, sometimes. And for the kind of things we were doing then, I was so heavily under the spell of Robert Wyatt – who was my real hero between ‘68 and ‘71 (as a drummer as much as anything else, but also as a singer) – that it was inevitable that it came out in what I was singing. (There were a lot of people imitating Robert Wyatt.)

I guess it was good for me not to sing for a while, just to get away from him and find something else that my voice could do. But it wasn’t until ‘77, when I started to go and see all the new punk bands, that I began to see the glimmerings of possibilities of singing, which didn’t necessarily have to mean that I could sing. When I saw Polly Styrene with X-Ray Specs, or when I heard The Sex Pistols for the first time, that had a very strong effect on me, just from the point of view of singing. And of course I’d also met Frankie Armstrong and Phil Minton at that time, and I’d been very impressed by both of them – much more so, from the point of view of any effect that it might have on me, than by Dagmar, whose skill seemed to me to be so extraordinary that it made me less likely to want to be a singer.

Q: What about singers who would manipulate their voices in the studio? The Residents, say, or The Beatles and their use of altered vocals?

Frith: Well, The Beatles are also fantastic singers. To date, my biggest moment as a singer was when somebody in Japan came up and said that I sounded like John Lennon. That was a real thrill, because he was for me the best singer, always. So I wouldn’t have listened to The Beatles except in a certain amount of awe, I guess, as far as singing is concerned. And after Frankie and Phil, The Residents were so weird that I really didn’t think of it as singing at all, actually. Especially since they do so many tricks with speed and harmonizers and all the rest of it. It’s not actually a real voice by the time they’re finished with it, except in an emotional sense.

Q: So singing for you was always bound up with live performance.

Frith: Very much so, because one of the values of singing is that it’s an absolutely direct connection from you to an audience. An instrument is something you have to pass through, whereas the voice is actually you. And I think that’s also one of the reasons why people who are not great singers get so traumatized by it: It’s such a direct communication that there’s always a fear of revealing yourself. When you get up and sing, it’s not just what you’re singing, it’s a question of who you are. And if you have any doubts about who you are, then that can be quite a heavy experience.

I suppose the final push over the edge was hearing David Thomas and also Christoph Anders. When I heard the Cassiber record, which Chris Cutler had written lyrics for, I was very impressed with the fact that Christoph was obviously someone who couldn’t really sing, but was absolutely committed and intense. The early Skeleton Crew singing was influenced by that idea of just shouting, which is all kind of post-‘77. And as we’ve gone along and I’ve gained confidence, we’ve started to include more melodic singing. Doing Cheap at Half the Price, I was able to really see just what kind of stage I was at, as far as singing. I tried the whole range of things: vocal harmony, high-up singing, low-down singing.

Q: Speechless was deeply concerned with inarticulately and the fear of communicating. Was making that album a kind of cathartic experience for you? Did it make it easier for you to begin singing again?

Frith: If Speechless has any concrete content at all, it has to do with being unable to say what you want to say. That comes through in a lot of the music – in quite a grim way, for me. (But it’s certainly not without humor.) And probably it did lay the groundwork. Because despite what the title says, it was the first time for a very long time that I’d actually sung on a record. On Speechless, we did a lot of vocalizing without words – which was quite painful to do, I mean emotionally, at the time, for sure.

Cheap at Half the Price was a different kind of pain! Because there’s the kind of singing where you’re being so totally expressive that you let it all hang out, and there’s the kind of singing where you’re making an artful imitation of something. There are elements of both on Cheap at Half the Price.

Q: Did you go back to singing because you wanted to get more overt political content into your music?

Frith: No, I think it would be wrong to say that. Working with Chris and Dagmar, I didn’t lack for direct political content. The decision to sing maybe has more to do with really feeling the need to find something in myself, to not always be apparently working through somebody else. That’s maybe why it was all so scary, because of this business of finding your own resources.

Link to:

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Contents

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Fred Frith Contents

For more on Fred Frith, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music: KALW Radio Show #1, A Few of My Favorite Things…

Music: SFCR Radio Show #6, Postmodernism, part 3: Three Contemporary Masters