99 Albums

Up until about 1979, Branca was involved in two NYC bands, Theoretical Girls (with Jeffrey Lohn, Margaret DeWys, and Wharton Tiers) and The Static with (Barbara Ess and Christine Hahn). Judging from his comments about them in the interview (and from the singles I’ve heard), their music was unusually twisted even by No Wave standards. Nevertheless, Branca felt he could go only so far with them: “Ultimately, my ideas were just too austere for these bands.”[1] Yet his early compositions – particularly Lesson No. 1, The Spectacular Commodity, Light Field, and The Ascension – are, for all their thorniness, far more lush and attractive than the Branca rock songs that made it onto disc: “You Got Me,” “My Relationship,” and “Don’t Let Me Stop You.”

What I think he meant by that comment is that his music was racing too far ahead of song format, in scale, personnel, and performance complexity – listening complexity too. So I guess he’s right. Wanting to do something more than divert clubgoers automatically does call down a certain austerity. Branca would eventually make this change in his musical attitude clear by waving the red flag of symphony; but you can read the alteration simply in the names of his first recorded compositions, Lesson No. 1 and Dissonance. That 99 Records EP, released in 1980, made official Branca’s transition from rocker to composer, a metamorphosis that began the previous year, with the premiere of (Instrumental) For Six Guitars.

Lesson No. 1, for four guitars, organ, bass, and drums, shows the impact of Philip Glass and Steve Reich on Branca. He’d been listening to them since the early ‘70s, and they “had an incredible effect on me. This was the direction I was going in, and these people had gone much farther than I had at the time.”[2] His use of repetitive phrases and a steady pulse in Lesson No. 1 owes a lot to them, particularly Glass. But something more is going on even here. You can hear it most plainly in the second half of the piece: The music is at its most driving and rocky, yet Branca is simultaneously cooling it down by working with an expanding series of cadences in the base. That’s very much his own kind of sound, as is of course the richness of the accompanying textures. A few years later, this technique would culminate in the extraordinarily beautiful finale of his Symphony No. 3 – but what he achieves here is nothing to sneeze at.

Dissonance is I think even more impressive than Lesson No. 1, if only because it’s so plainly Branca-esque – who else would score a piece for guitar, bass, keyboards, drums, and a sledgehammer? Here’s where the music sounds every bit as austere as the attitude behind it: industrial-sounding guitar and bass, sledgehammer clanks, visceral stretching of pitch, siren-like keyboards. Again, all gestures he would use to greater effect in his later music; but they give this highly original piece a memorable ferocity and strength.

The EP, says Branca, “was basically a two-day wonder – one day to record, one day to mix – and I wasn’t too pleased with the quality.”[3] But despite these limitations, the results were impressive. It’s a shame that Branca didn’t have a little more time (= $) to work on this record, because those two works were scored for instruments that can come across well in the recording studio. On his next 99 album (and his first LP), The Ascension, all the pieces are scored for four electric guitars, bass, and drums – the multiple-guitar sound for which he is still best known. That kind of music has proven to be a lot more difficult to transfer adequately to disc: Yet all things considered, Branca got some amazing stuff onto the album (overdubbing helped). With these five compositions – Structure, Lesson No. 2, Light Field, The Spectacular Commodity, and The Ascension – there’s no longer a question of trying to spot influences or cite precedents: This music sounds like nobody else but Glenn Branca. Which means it often sounds like nothing that’s ever been heard before.

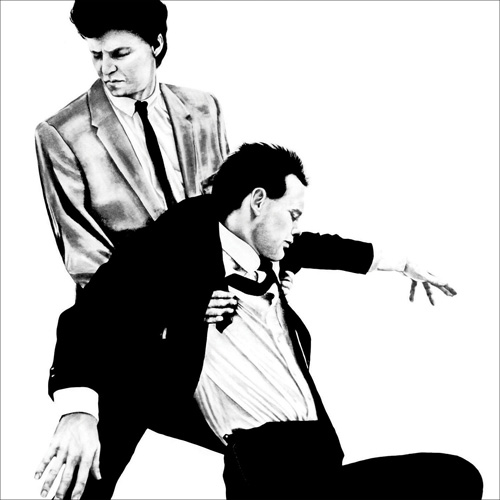

To someone coming to this music cold, the most striking quality of the album would probably be the sheer range of its sound – Branca gets an incredible plasticity out of the electric guitars. Over the brief three minutes of Structure, they mutate from brittle metallic spiders to a blinding geyser of steam. For much of Light Field, they sound like heavy-metal autoharps. And in The Ascension, at one point or another, they become just about any event you’d care to name – instrumental, vocal, or electronic. But the real glory of this music is what he does with these malleable instruments. And as a composer, his most successful piece on the album is The Spectacular Commodity. Surprisingly, this work, which stands out for its expressive range and precision of gesture, is also one of Branca’s earliest pieces. An outgrowth of his music with The Static, it was premiered by that trio in August of 1979 as music for Eiko and Koma’s dance Fluttering Black. I’ve never heard it in that form, but I can’t imagine that version approaching the power and richness of the LP’s arrangement for his ensemble.

Branca opens The Spectacular Commodity with a loud, ringing chord, slamming it six times, with plenty of space between each statement so you can hear its high echoing overtones – and each afterglow is richer than the last. He moves on to a simple melodic cell, and as more guitars enter to state it, the volume increases and the harmonies grow gloriously dissonant, until rough, frenzied, electric-drill guitars are locked into a mean battle with the rhythmically unrelated hammering of Stephan Wischerth’s drums.

Part two fades up out of this barbed wire, with the guitars rocking back and forth on a variation of the cell. Again the ferocity builds, helped by the addition of the bass, and the music accelerates until it careens into a wall of changing chords, cemented together with the wild dance of the drums. Finally one chord is heard for the familiar six times, but it’s harmonically weighted to incline toward a further chordal resolution, which turns out to be the chord heard at the start of the piece. Branca sounds that one four times, but adds three strokes on the bass after each statement, making the music champ at the bit for a headlong gallop. And boy does it ever take off, into a driving passage that culminates in an audacious visceral effect, a gargantuan upward glissando that stretches you like a piece of taffy. And after he snaps the last strings connecting your head to your body, Branca stuffs 19 cords into the stump of your neck – the opener again, but this time rattling by so quickly that it becomes an incantation for new action, rather than a return to home.

These chords call down the third and final part of The Spectacular Commodity. Branca cuts directly from his previous meter of four to an unsettling five, creating an image of the guitars climbing in pitch only to weirdly fall back in on themselves – the aural equivalent of a flipping television picture. The effect is strongest at the start, when you think you’re still in four but with all the parts crazily refusing to fit. As this Escherscalator keeps on going up to its point of departure, Branca distracts you with flashes of other events, each of which lasts only for a few measures: a high pitch that glissandos upwards, demarcating the start of each successive measure; a hot, lovely counter-rhythm from a wild jabbering voice in 16ths; a simple rhythm of five eighth-notes, which takes a pause of 3/8 between statements, and so briefly superimposes a meter of 8/8 over this looped 5/4 juggernaut.

A rhythmic seesawing between high and low sustained tones fades up, glistening from one to the other in what becomes an independent meter of four. And on that majestic four, with the first and third beats calmly chimed like bells, The Spectacular Commodity sails out into its brilliant finale. As that chiming becomes more harmonically elaborate, Wischerth’s drums glide through this golden section, inviting other glittering gestures to enter one after another. The proliferation of all these radiant sounds builds into one of the most glorious passages in all of Branca’s music. And yet there’s no letdown when he reins in the extra events, clearing the canvas so he can plainly paint a simple melodic figure (also derived from the piece’s basic cell). In the unobstructed view that Branca gives it, this enchanting moment reaches its apotheosis, because more activity begins to spill out of it all over again. The music finally shudders into fifteen climactic, gonglike strokes of the opening chord, but Wischerth keeps kicking up the dust, refusing to let things end here, and his drumming ecstatically discharges pointillistic guitar chords that in turn release incandescent strobe-like rhythms, briefly illuminated by a high counter-rhythm that signals the paroxystic conclusion, this cataract funneling into chords of growing harmonic complexity, airplane wheels hitting the ground with a little more finality each time, until Branca can at last stop by finally fully sounding the one chord that started the work.

The Spectacular Commodity is a knockout, yet Branca tends to dismiss his early guitar pieces as “a dead end” – and this is precisely the kind of piece he’s alluding to. It has nothing to do with densities, new instruments, or the harmonic series; it’s just Branca taking his brand of ‘art rock’ as far as he can. (And he really catches you between rock and an art place – parts of this piece are really bitchen.) But I suspect that The Spectacular Commodity doesn’t simply string together these earlier techniques and ideas, but rather distills them; just about everything that music could do well, this piece must be doing best. The Ascension is exactly the reverse: Branca’s first attempt to really compose for the unprecedented new sounds his music was releasing. And although The Spectacular Commodity may have sounded most impressive to people who bought the LP, it was the live performances of The Ascension that really put Branca on the map. When he premiered his Symphony No. 1, it was the reputation of The Ascension which prompted a lot of the attention he received.

That reputation, as well as his own regard for the piece, persuaded Branca to name the LP after The Ascension, even though it actually suffered more in being vinylized than any of the other works on the record. Which was obviously very frustrating for him – the stuff he’s most interested in, people are hearing the least. But in light of where that interest would take him, The Ascension seems to me more tantalizing than satisfying. The recorded version is admittedly somewhat limp, but even in a decent live performance, the piece is still only an initial step toward the kind of music Branca really has in mind – a Symphony No. 0. (It may well have been his actual discovery that that kind of music could exist, and that he could make it.)

Dense masses created by strumming guitars open The Ascension. What’s most startling about them is their illusion of size and gentle motion – it’s as though you were actually entering physical clouds of sound. All sorts of new colors and textures swell out of that mass, especially once it becomes LOUD. And then, amazingly, this powerful cloud simply evaporates, quickly and completely. The second mass is even more rich and detailed; Branca may sit on it a little too long, but from it he gets perhaps the most extraordinary music in the entire piece. It seems impossible that all you’re hearing are electric guitars; at first you’d swear there were banjos and harmonicas somewhere in the ensemble. Then, as Branca gradually pulls this cloud apart, slowing down the guitars and moving them into higher registers, you can clearly hear vocal timbres, and from the voices high electric keyboards, on into golden, cascading brass textures.

Branca would realize this kind of music more powerfully in his symphonies, where the aggregates would have a far greater complexity; but even here the results are arresting. Unfortunately, the rest of The (recorded) Ascension fails to equal the originality of its opening. The nadir is the second section, where Branca cuts back and forth between two fast gallops, until he finally slams to a dead, silent halt – material simply not novel or varied enough to sustain the time he spends on it. Worse, he digs into that sudden silence, then cuts back to the action, takes another rest, another rush, etc. Unlike the opening of The Spectacular Commodity, almost nothing hangs in the air of these pauses – and the other stuff hasn’t been wild enough to in turn make this blankness really interesting. The final third is more successful, even though it doesn’t fully survive its transition to disc. Branca interweaves a majestic ride and an abstract, visceral, and very loud music, letting each grow more dense and mad and hallucinatory. But the visceral passages never really communicate the actual, physical feeling of ascent. (Live, Branca does manage to make his point!) The ending, however, is superb: The guitars and drums rev up into a mighty spin which is transfigured by the crazed extremity that’s at the heart of Branca’s music. His ferocious pirouette tears on and on, expanding on its own energy, deliriously persuading you that it might continue forever, and that that wouldn’t be such a terrible thing.

FOOTNOTES

1. David Orr, “Glenn Branca” in Terminal!, December 1985, p. 6.

2. John Schaefer, “New Sounds” in Spin, September 1985, p. 53.

3. Kristine McKenna, “Glenn Branca’s Heady Metal” in New York Rocker, November 1981, p. 25.

Links to:

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Glenn Branca Essay, part 4

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Glenn Branca Contents

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Contents

For more on Glenn Branca, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music Book: Soundpieces 2: Interviews with American Composers

Music Lecture: The Secret of 20th-Century American Music

Music: KALW Radio Show #1, A Few of My Favorite Things…

Music: SFCR Radio Show #7, Postmodernism, part 4: Three Contemporary Masters