“Ask the nautilus shell”

In his program notes to Symphony #5, Branca writes, “When we hear any tone, we usually experience it as a singular manifestation (as a single tone). In fact, a tone is a combination of partial tones in varying degrees of volume and pitch, often in unstable or changing relationships. In music, or speech, or natural sound, every tone is really a chord.” That these partial tones, or harmonics, simultaneously accompany any single tone when it sounds. In fact, that single tone, known as the fundamental, is simply another harmonic; because its fellow partials are higher and quieter – and because music ordinarily emphasizes only this facet of the sound – we tend to identify the fundamental as that sound.

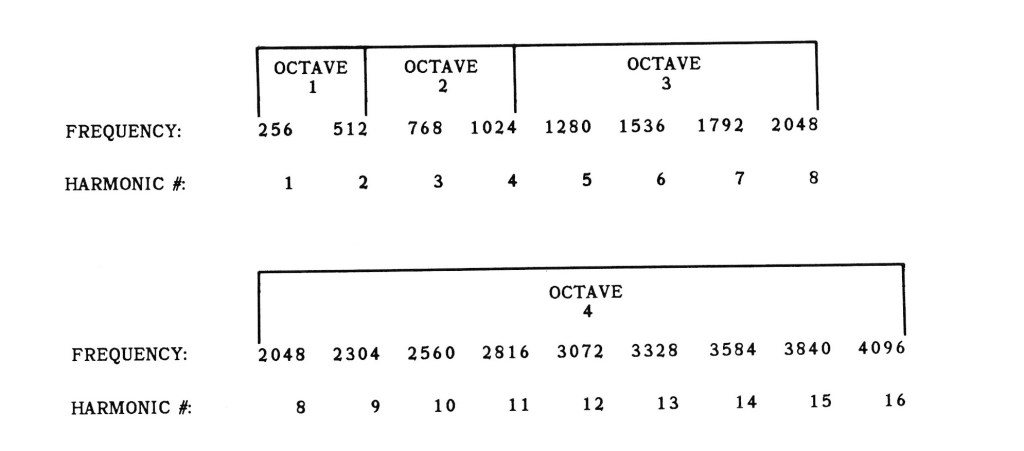

Harmonics occur in a precise pattern known as the harmonic series. The chart below gives the first 16 harmonics for a fundamental (harmonic #1) whose pitch has a frequency of 256 beats per second – which puts us at middle C. The second harmonic occurs exactly one octave higher than the fundamental: another C, this one at 512 beats, doubling the frequency of harmonic #1. The third harmonic is, yes, another 256 beats higher: It has a frequency of 768, which makes it a G, a perfect fifth above #2. And so it goes – harmonic #4 has a frequency of 1024: twice the frequency of #2, hence an octave higher, and our third C.

The fifth octave contains 15 harmonics, #s 17–31; the sixth, 31 harmonics; the seventh, 63; and so on, and on and on.

As more and more partials proliferate within successive octaves, the distances between them steadily decrease. The interval from #2 to #3, a fifth, is smaller than the octave defined from #1 to #2. The distance from #3 to #4 is only a fourth (G to C); from #4 to #5, a major third (C to E). The ratios between harmonics soon become smaller than any intervals available in equal temperament: Harmonic #16 is only a semitone above #15. “The last interval within the seventh octave,” as Dane Rudhyar described it, “is the expression of the ratio 128:127; it is so small an interval that the ear cannot distinguish it from the following interval, 129:128.”[1]

Branca had been releasing and manipulating all sorts of ordinarily obscured harmonics since his theater music of the 1970s, but he really took off as a composer once he saw how guitars could create new extremes of density. Devising alternate tunings for the guitars was the next, inevitable step, because a music of partials can’t be restricted to a tuning system that’s based on ignoring partials. By 1984, he saw equal temperament as Big Brother: “an idiosyncratic, limited approach to the ordering of tone, which has become so completely absorbed that we have become partially deaf to music that doesn’t exist within its boundaries.”[2]

Branca says he first became curious about the harmonic series because of its prominence in La Monte Young’s music. Conversations with former Young pupils Rhys Chatham and Ned Sublette gave him some insights into the subject, but it took Dane Rudhyar’s 1982 book The Magic of Tone and the Art of Music to demystify the harmonic series for him.[3] He has studied it with a typically extreme thoroughness ever since, and now recognizes in it the fundamental pattern underlying everything we know, a blueprint that unifies reality: “There seems to be no form in which it doesn’t exist.” The harmonic series is what Branca has always been searching for, like the Knight in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal; it’s his proof in writing that there is a basic, primordial order and intelligibility to life, that formlessness and chaos do not exist. This idea has changed the course of his work: “There are some aspects of what I want to do, which aren’t concerned with music; they’re concerned with directing attention specifically to the harmonic series.”

The first phase of this massive awareness campaign was Branca’s Symphony No. 3, which he subtitled “music for the first 127 intervals of the harmonic series.” For him, the power of these tunings is that they’re true – not just to his music, but to the nature of sound itself. He isn’t systematizing from the perspective of how can I order the chaos of sound? He’s using the harmonic series to get sound to come across clearer and more fully, and to challenge his own sense of order – “the whole Cageian point of view,” know what I mean?

And like Cage, Branca is also an inheritor of the classic American modernist/experimentalist tradition, the music of Ives, Varèse, Ruggles, Partch and Cowell (to name the more obvious examples). Just as they did, Branca has bypassed the history of most of Western music and gone straight to the heart of his discoveries. He’s taking this music to extremes, giving it his undivided attention, and keeping the faith that it can reveal something of value.

What it revealed by January of 1983 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music was his Symphony No. 3 – and those performances are among the most memorable concerts I’ve ever attended, regardless of genre. I’m not calling Symphony No. 3 one of the best pieces of music I’ve ever heard; I’m saying that, despite my familiarity with other works of Branca’s, I’ve never had an experience similar to hearing this piece. By the time the symphony was over, I’d run through the entire spectrum of responses: some stuff I thought was beautiful, other passages left me cold, feelings of shock, dismay, joy, confusion, awe – all the positions. But one response was constant and is with me still, that it doesn’t matter what anyone thinks of this music, just as it doesn’t matter what anyone thinks of the sun. Hearing the opening of Symphony No. 3 was more like witnessing an event of nature than attending a concert. The music travelled through one sound field after another, letting you decipher the richness and strangeness of each, until one arrived that stayed and altered and swelled, the bass finally exfoliating out of it in a visceral surge that was in turn absorbed into the exuberance and affirmation of the climactic drums – it was like watching vapors and gases and dust coalescing into a planet, down to seeing the final veins of green snake through it, complete it, and lock it into life.

At the time, I didn’t realize that I was listening to something which was, for Branca, “a very ideal representation” of the harmonic series. Instead, I was intrigued by how, in its basic shape, the first movement of Symphony No. 3 reworked the opening of his Symphony No. 2[4]: a journey through hallucinatory chords, which climaxes at one so rich it tops everything else – and then Stephan Wischerth comes in and lifts it off the ground. But I could also hear that something had changed profoundly for Branca since Symphony No. 2. Paradoxically, that earlier, more intuitive and experimental work had, to my ears, a certain coolness and reserve; whereas the meticulous, mathematical, impersonal structure of Symphony No. 3 revealed a profoundly moving, hair-pulling joyousness. Branca’s first harmonic-series score, this eureka shout, is still for me one of the few sublime musics I know.[5]

FOOTNOTES

1. Dane Rudhyar, The Magic of Tone and the Art of Music. Boulder: Shambhala, 1982, p. 57.

2. Branca’s program notes to Symphony No. 5.

3. Rudhyar was born Daniel Chennevière in Paris on March 23, 1895. He came to America in 1916 and settled in California, where he died in 1985. Besides composing (principally for piano), he was also a painter, poet, novelist, and the author of many books on philosophy, mysticism, and astrology.

4. Which in turn would be reworked, yes, to begin the Symphony No. 4.

5. By subtitling Symphony No. 3 “Gloria,” Branca says the same thing, only with more gratitude – and also gets to tip his hat to Van Morrison. (Similarly, the subtitle of Symphony No. 2, “The Peak of the Sacred,” managed to be stained-glass pure and subversively, atheistically Feuerbachian at the same time.)

Links to:

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Glenn Branca Essay, part 9

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Glenn Branca Contents

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Contents

For more on Glenn Branca, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music Book: Soundpieces 2: Interviews with American Composers

Music Lecture: The Secret of 20th-Century American Music

Music: KALW Radio Show #1, A Few of My Favorite Things…

Music: SFCR Radio Show #7, Postmodernism, part 4: Three Contemporary Masters