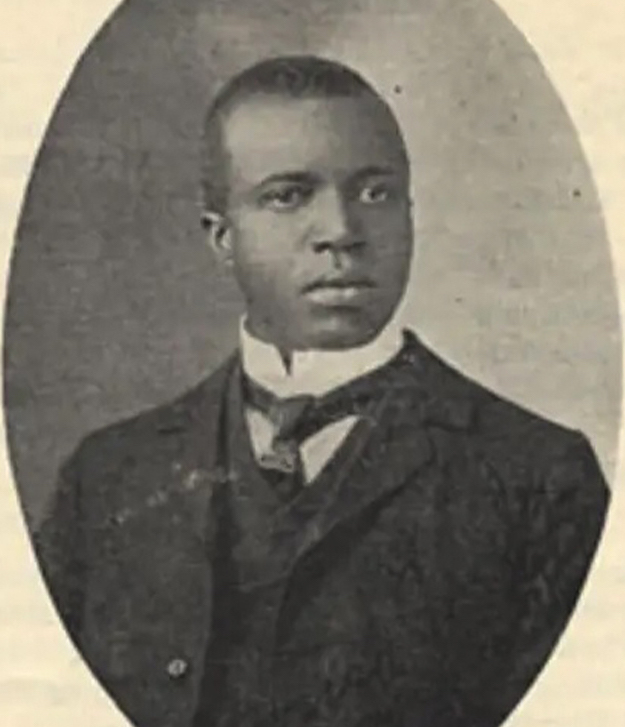

King Without a Country: Scott Joplin, the King of Ragtime

Hello friends and thank you for joining me for this afternoon’s talk about the life and music of Scott Joplin. For the next hour or so, I’ll be discussing this man and sharing with you some of his finest works. In his lifetime he was known as the King of Ragtime. And he was. But today I’d like to speak of him as I think he would most want to be remembered: as one of America’s greatest composers.

Biographical data is sketchy, especially for Joplin’s early life. He was born probably in 1868 in northern Texas, probably around Linden, and relocated with his family to Texarkana in the early 1870s. His father was a former slave from North Carolina, who worked for a railroad in Texarkana when Scott was young; his mother was freeborn, from Kentucky. Both parents were musical – the father playing the violin and the mother playing the banjo and singing – and Scott showed musical talent at an early age. His mother worked as a domestic in a home with a piano, and she got permission to bring young Scott with her and let him play the piano as she cleaned. Scott’s gifts became known to a German-born music teacher named Julius Weiss who was then living in Texarkana, and he gave Scott lessons for free and exposed him to certain classical composers. Eventually his mother was able to buy a piano, and Scott would play at church socials and school functions. By age 16 he formed a vocal quartet that performed in the region; Scott was also teaching guitar and mandolin by then. And throughout these years he was busy absorbing all the various musical activities around him: hymns, plantation songs, work songs, spirituals, hollers, waltzes, marches, and popular dances such as two-steps and cakewalks.

When he reached his late teens, Scott struck out on his own as an itinerant musician, traveling through the South and the Midwest, playing in dance halls, gambling dens, houses of ill-repute, as well as more respectable venues – men’s clubs, social events, etc. – sometimes as solo pianist, sometimes in bands, including brass bands with Scott on cornet. He had adopted the practice among other wandering pianists of playing in what they called “ragged time,” with the left hand providing a steady pulse, against which the right hand could syncopate melodies, creating rhythmic energy and surprises by accenting off-beats. Ragged-time playing had its roots in Black plantation and church songs – music that reflected the complex rhythms of earlier African singing and drumming.

Joplin was in Sedalia, Missouri, in 1895, and there he was able to publish his first compositions – songs, a waltz, marches – which had some elements of ragtime. Published scores of piano rags, composed by both Black and white musicians, became increasingly popular in those years, and in 1897 Joplin found a publisher for a piece of his entitled “Original Rags.” He also took some classes in piano, theory, and composition at the George R. Smith College for Negroes in Sedalia. And in 1899, his composition “Maple Leaf Rag” was published by John Stark, a white man who befriended Joplin. Stark began promoting the score in earnest, printing some 10,000 copies of “Maple Leaf Rag” after he relocated his firm to St. Louis in 1900. Joplin also moved to that city soon after, because in that first year of the 20th century, his score just took off: By 1905 Stark was selling 100 copies per day. Joplin had a royalty agreement with Stark for “Maple Leaf Rag” – which was not then the usual practice with sheet-music publishers – and this income was a real boon for him. The work also brought Joplin nationwide attention, and soon he was being celebrated in newspapers and by music publishers as “the King of Ragtime” – just as Johann Strauss Jr. had been proclaimed the “Waltz King” and John Philip Sousa the “March King.”

“Maple Leaf Rag” set the standard for what came to be known as “classic” ragtime, played at a moderate tempo and employing four different melodies, repeated and played sequentially: A-A, B-B, then a reprise of A, then C-C, D-D. Let’s listen to this landmark work now. The pianist is Joshua Rifkin.

I think you can appreciate how the exuberance and vitality of “Maple Leaf Rag” captured the public’s imagination. It was also performed in all sorts of arrangements after its publication. There’s a wonderful story of this piece being played in Washington, D.C., at the White House around 1905. President Theodore Roosevelt was holding a diplomatic reception, and his 21-year-old daughter Alice approached William H. Santelmann – a German immigrant who was then leader of the U.S. Marine Band – and according to one of the musicians, Alice said to him, “Oh Mr. Santelmann, do play the ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ for me.” When he protested that he’d never heard of the piece and it wasn’t in the band’s repertory, Alice laughed and she said, “Now, now Mr. Santelmann, don’t tell me that. The band boys have played it for me time and again […] and I’ll wager they all know it without the music.” Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag” was performed that day – and indeed band parts for it, dating back to 1904, have been found in the Marine Corps Historical Center.

Joplin’s musical ambitions increased dramatically after “Maple Leaf Rag,” and as early as 1899 he had formed a company of musicians, dancers, and a narrator to perform a special work of dance theater, a musical tableau of African American dances, essentially a folk ballet, which he called The Ragtime Dance. But there were few performances, and the score’s publication in 1902 sold poorly. What did hit with the public in the early 1900s, however, were such classic piano rags by Joplin as “Peacherine Rag,” “The Easy Winners,” “Elite Syncopations,” and “The Entertainer.”

In these years Joplin’s music was also being promoted by Alfred Ernst, another German immigrant. He was then director of the St. Louis Choral Symphony Society, and in 1901 he spoke to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch about Joplin: “I am deeply interested in this man. He is young and undoubtedly has a fine future. With proper cultivation, I believe his talent will develop into positive genius. Being of African blood himself, Joplin has a keener insight into that peculiar branch of melody than white composers. His ear is particularly acute. Recently I played for him portions of Tannhäuser. He was enraptured. I could see that he comprehended and appreciated this class of music. […] The work Joplin has done in ragtime is so original, so distinctly individual, and so melodious withal that I am led to believe he can do something fine in compositions of a higher class when he shall have been instructed in theory and harmony. […] He is an unusually intelligent young man and fairly well educated.”

There was talk of Ernst taking Joplin with him on a tour of Europe, but that trip appears never to have happened. Still, Joplin kept aiming higher, and in 1903 he composed his first opera to his own libretto, a one-act work entitled A Guest of Honor. He formed the Scott Joplin Ragtime Opera Company, and his small group of singers and musicians toured through Iowa and Missouri, but the box office was poor and the troupe had to disband; what’s worse for us is that both music and text were lost and have yet to be recovered.

Once again, what scored with the public were Joplin’s piano rags of 1903, ’04, ’05, including “Weeping Willow,” “The Cascades,” and “Eugenia.” But this phase of his composition also reflected his higher aspirations, with his 1904 works “The Chrysanthemum,” which he subtitled “An Afro-American Intermezzo,” and “The Sycamore,” designated “A Concert Rag.” And there was his brilliant score of 1905, “Bethena – A Concert Waltz.”

With both The Ragtime Dance and A Guest of Honor, Joplin was able to develop his skill at arranging his own music. In 1909 Stark would publish a collection of ragtime orchestrations he called Fifteen Standard High Class Rags; it was popularly known as The Red Back Book because of its red cover. Although none of its arrangements were by Joplin, this music was played – and finally recorded in the early 1970s, by Gunther Schuller leading the New England Conservatory Ragtime Ensemble. That LP was a big hit, and it led directly to the decision to use Joplin’s music in the score of the 1973 film The Sting.

The enthusiasm for arranging Joplin’s piano music, launched with “Maple Leaf Rag,” has never receded – today we can hear Scott Joplin’s music in endless different versions, from chamber groupings of two or more instruments to small bands to large ensembles. And I have to say, to my ears, these arrangements always sound inferior to Joplin’s original piano scores, they invariably inhibit the emotion and expressivity of his music. Now, different arrangements never seem to impact adversely the music of Bach, whose scores are constantly being arranged and rearranged. But Bach composed a music of counterpoint, of different lines moving along horizontally. In fact, arrangement for multiple instruments often benefits listeners, because the different instrumental voices can clarify the polyphony of the various musical lines – something that can start to mash together when you hear that music played on a harpsichord or an organ. You’ll notice, however, that almost nobody bothers to arrange or orchestrate the music of Chopin. That’s because Chopin was a piano composer who explored melody and harmony, and when the singing tones of his singular instrument are replaced by a group of different instrumental voices, the nuanced atmosphere and emotion in his music starts to dissipate. Joplin suffers in arrangements for the exact same reason. Which only makes sense, because Scott Joplin is our Chopin, he is the American piano genius of nuanced atmosphere and emotion.

His music can be exuberant, as in “Maple Leaf Rag” or “Elite Syncopations”; it can be brilliant and glittering, as in “The Cascades”; tender and affectionate, as in “The Chrysanthemum” or “Bethena” or “Leola”; clever and charming, as in “Stoptime Rag” with its foot-stomping obbligato. Joplin can be nostalgic, as in the evocative strains of “The Entertainer”; he can be stately and dignified, as in “Country Club”; he can be coy and playful, as in “Ragtime Dance,” a piece he distilled from his dance suite. His music can be forward-looking, as in the advanced harmonic language of “Euphonic Sounds,” which he subtitled “A Syncopated Novelty”. He can also be programmatic: “Great Crush Collision March” depicts an intentional head-on collision that destroyed two locomotives, a public-relations stunt that drew some 50,000 spectators in Texas in 1896. Joplin gave the dissonant passages of this march the headings “The noise of the trains while running at the rate of sixty miles per hour,” “Whistling for the crossing,” “Noise of the trains,” “Whistle before the collision,” and “The collision.” His “Wall Street Rag” is another example, with Joplin evoking the Panic of 1907, each of the four strains having its own descriptive heading – “Panic in Wall Street, Brokers feeling melancholy,” “Good times coming,” “Good times have come,” and “Listening to the strains of genuine Negro ragtime, brokers forget their cares.” Joplin’s music can also be bitter and sarcastic, as in the mechanical, assembly-line rhythms of his penultimate work, which he titled “Scott Joplin’s New Rag.” And it can be melancholy and contemplate death, as in his final score, “Magnetic Rag.”

Joplin can also express a quality that is almost unique to his music, an intangible sensibility, an uplifting sensation that I can define only as nobility. Specifically, he is reinvesting Black people with the self-respect, the dignity and stature and value that white America worked relentlessly to strip from them. But he’s also doing this for all of us who are commodified, all of us who find ourselves trapped inside the belly of a consumer society. You hear this sound over and over again in his music, especially in the C and D sections in such works as “Pine Apple Rag” and “Weeping Willow” and “Paragon Rag” and “Eugenia” – an indomitable refusal to be beaten down.

Here’s a classic example: Scott Joplin’s “Gladiolus Rag,” composed in 1907, as played in 1970 by Joshua Rifkin.

The composer Virgil Thomson came up with a wonderful line when he was comparing Aaron Copland to another very successful American composer, Elliott Carter: “At least when Aaron made it to the top, he sent the elevator back down again.” The King of Ragtime was also one of those people who sends the elevator back down: Scott Joplin promoted and sometimes collaborated with several other ragtime composers who went on to achieve prominence, all of whom were then younger people struggling to make a name for themselves in what had become a flourishing and popular movement in American music. Looking back on the ragtime era, musicologists have come to regard two figures as standing alongside Joplin at the pinnacle of ragtime composition. They were James Scott, a Black composer/musician from Missouri, and the white composer/musician Joseph F. Lamb, born in New Jersey. Both were young men, about age 20, when they deliberately sought out the older Joplin, because they quite rightly regarded him as a master. In 1905 James Scott played some of his music for Joplin, who was greatly impressed and immediately hooked up the young man with his own publisher, John Stark. Stark would relocate to New York City later that year, but he went on to publish 27 of James Scott’s rags over the next 16 years. Joplin performed the same service for Lamb in 1907 – the year Joplin settled in New York, which is where he met Lamb and sent him to Stark, launching Lamb’s career; there would be a dozen Stark publications of Lamb’s music. Joplin and Lamb also collaborated on composing a rag, but the score has alas yet to be recovered.

Other collaborations by Joplin with African American composers, however, did see the light of day. The teenage Arthur Marshall became friends with Joplin in the late 1890s, and the two worked together on Marshall’s Swipesy Cake Walk and Lily Queen, published in the 1900s. Scott Hayden, also some 15 years younger than Joplin, collaborated with him four times, on Hayden’s Sunflower Slow Drag, Something Doing, Felicity Rag and Kismet Rag. Marshall retired from music in 1917, but he lived into his eighties and became an important primary source on Joplin; Hayden died of tuberculosis in 1915, age 33, leaving behind only those four collaborations plus an unfinished solo work called “Pear Blossoms.”

There are two Joplin collaborations I want you to consider today. Both date from 1906, and both were made with other Black composers.

The first one I want you to hear is especially significant because it points to the end of the ragtime era – although this style was still going strong in 1906 and wouldn’t enter an eclipse until the late teens. This collaboration brought Joplin together with one of the most remarkable figures in American music, a man named Ferdinand Joseph Lemott, better known by his professional handle: Jelly Roll Morton, the self-proclaimed inventor of jazz.

In 1905 Jelly was in Mobile, Alabama – he was maybe in his early twenties by then – and as he later told his biographer, the musicologist Alan Lomax, it was in Mobile that he met the celebrated ragtime pianist Porter King: “A very dear friend of mine and a marvelous pianist[, …] an educated gentleman with a far better musical training than mine, and he seemed to have a yen for my style of playing, although we had two different styles. He particularly liked one certain number and so I named it after him, only changed the name backwards and called it ‘King Porter Stomp.’ I don’t know what the term ‘stomp’ means, myself. There wasn’t really any meaning, only that people would stamp their feet. However, this tune became to be the outstanding favorite of every great hot band throughout the world that had the accomplishment to play it.”

Which was true: Once Jelly lost control of the copyright, the piece found its way into the repertory of innumerable swing bands throughout the 1930s, including Benny Goodman’s. Jelly had first developed this piece around 1902. But according to witnesses a few years later, not only did Porter King contribute more than his name to the piece, but King and Morton also sent the score to Scott Joplin, asking him to add more to it and to arrange it. After which Jelly rearranged it further and copyrighted it in 1906. Finally in 1924 it was published.

Musicologists have been scratching their heads over the piece’s history ever since. To my ears, however, Joplin’s participation is crystal clear, however much Jelly may have revised it further. I’m going to play for you a performance from 1923, a piano roll of Jelly Roll Morton playing his “King Porter Stomp.” And you’ll hear how this piece from the mid-1900s follows the basic outline of classic ragtime, with sections A-A, B-B, C-C, D-D.

Only this is a 1920s performance with a jazz vocabulary – an innovation in which Jelly was a crucial figure. So here the repeats are all further developments and expansions of the original tunes. Jelly also included an opening introduction, and he replaced the third A with a short bridge between the second B and the first C; he even added an E-E strain. But when I talk about the sense of uplift and nobility Joplin could create, I can hear its glow, plain as day, in the reiterated tones that distinguish both the C and D strains. Judge for yourselves.

In that 1923 performance by Jelly Roll Morton, you can hear the one quality that distinguishes “King Porter Stomp” from classic ragtime: its speed. The quick tempo Jelly employed is characteristic of jazz, particularly from the 1920s. That fast tempo, however, is not what classic ragtime is about, not at all. But in the first years of the 20th century, ragtime performance was changing in the red-light districts of major American cities. The music was being played more quickly, with pianists vying to demonstrate just how fast a tempo they could articulate. Joplin resisted the cutting contests and other competitions so many of the musicians were fond of, because he was not any kind of piano virtuoso, seeing himself more as a composer than as a performer. He understood that the music he was making reflected the dance tempos of the cakewalks and two-steps, the slow drags. But the newer generation that came up wanted to display their chops, and because Joplin shunned competitions, there would be those pianists in the clubs and honky-tonks, who would urge Joplin to play “Maple Leaf Rag” for them. And then they would try to show him up by playing their own high-speed versions of the piece, much to Joplin’s dismay. Remember that line of Joplin’s about stockbrokers forgetting their cares by “listening to the strains of genuine Negro ragtime”? Well, what was also dismaying Joplin in these years was the flood of inferior, trendy rags being published by the mostly white composers of New York City’s Tin Pan Alley.

So Joplin deliberately tried to clarify how this music should sound. A lovely piece of his from 1902, a march and two-step that he called “A Breeze from Alabama,” includes an explicit tempo indication on the score: “Not fast.” In the score of his rag Leola from 1905, Joplin warns the pianist, “Notice! Don’t play this piece fast. It is never right to play ‘rag-time’ fast.” By 1912 he was openly mocking the new style of playing in his piece “Scott Joplin’s New Rag.” Nevertheless, endless pianists – and performances of ensemble arrangements – have persisted in jazzing up this music and playing it TOO DAMN FAST!

Let me digress for a moment and point out that this business of playing ragtime too fast is a classic example of our inability to appreciate our own cultural heritage. It’s totally analogous to the way that we distorted silent films, for decades. Silent movies were photographed and projected at a speed of 18 frames per second. When sound came in, the soundtrack was attached directly onto the film, but for it to synchronize properly, the film had to be photographed and then projected at 24 frames per second. Sound projectors replaced the silent projectors, and so when a silent movie was revived, it was played on a sound projector, which meant that the silent film was now running about 33% faster, at 24 frames per second instead of 18. Which obliterated the atmosphere and emotion and realism of the silent film, because everything was now speeded up and looked herky-jerky and silly. And that became the cliché of what silent movies were like. Today it’s another story, now that virtually everything is being seen digitally, and these films are again being appreciated for what they actually are.

A similar insensitivity has plagued a lot of ragtime playing. That’s why I’m relying on Joshua Rifkin’s performances for today’s discussion. Because he played Joplin the same way he’d play Bach: By going to the score and following the composer’s instructions and playing the music as it was written down, without showing off or tricking it up. And the 1970s recordings by Rifkin for the Nonesuch label were decisive in launching the rediscovery of Joplin’s artistry.

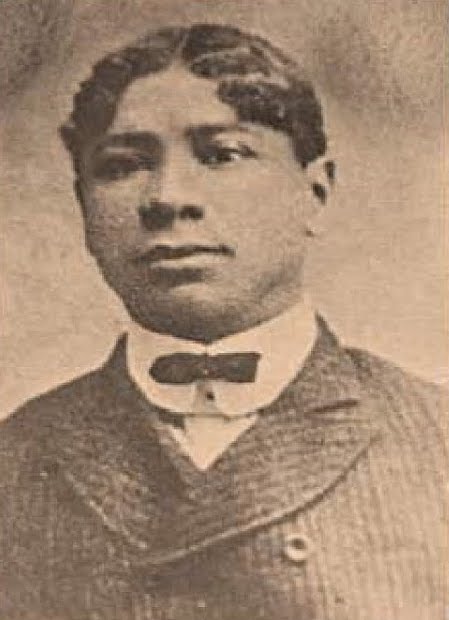

I said I was going to play for you a second Joplin collaboration. And it is no accident that the composer he worked with was atypical among the St. Louis ragtimers of the 1900s, because this person stuck to the older, slower tempi, and emphasized the legato singing line over the quick staccato attacks that were then in vogue. But despite this individual’s contrariness, his gifts were so profound and original, and he was such a virtuoso at the keyboard, invariably winning whatever competitions he entered, that he was universally admired by his peers. I’m referring to a young Black composer/musician, born in St. Louis in 1881, named Louis Chauvin.

And that name has become legend, because of the stories of his prodigious talent and because today we have virtually none of his music – Chauvin could neither read nor write a score, he did everything by ear. All that remains of his art are the music he provided for two songs that were published in the 1900s, and this one collaboration with Scott Joplin. The musician Sam Patterson, who was Chauvin’s good friend from boyhood, recalled decades later, “He had lots of original tunes of his own – never had names for them. He would sit right down and compose a number with three or four strains. By tomorrow it’s gone and he’s composing another. You can talk about harmony – no one could mistake those chords. Chauv was so far ahead with his modern stuff, he would be up to date now. As a boy I thought I was some peanuts, but I knew then I would not be the artist Chauv was. I had lessons, and he taught himself. When he was 13 you never heard anything like him. When he would first sit down, he always played the same Sousa march to limber up his fingers, but it was his own arrangement with double-time contrary motion in octaves, like trombones and trumpets all up and down the keyboard. And Chauv had so many tricks, my God, that boy!”

By the late 1890s, Scott Joplin had become very deliberate about not falling into the life of the tenderloins and red-light districts from which ragtime had emerged – the brothels, gin joints, dance halls, gambling parlors, and yes opium dens. The sporting life was irresistible to Chauvin, however, and with his enormous musicianship, he could make money very easily. He squandered it easily too. But he was young and slight in stature, and he simply couldn’t withstand the physical toll of such a life. By 1908 at age 27, he was dead. But in 1906 Joplin was in Chicago when Chauvin and Patterson were there as well, and Chauvin played for Joplin two ragtime themes he had been working on. Joplin was greatly impressed and started developing two more themes to accompany them – the C and D sections to Chauvin’s A and B. Joplin completed the work, scored it and got Stark to publish it in 1907 under the title “Heliotrope Bouquet.” And it is one of the most achingly beautiful compositions in the ragtime literature. Here’s how Rifkin plays it:

In Joplin’s C strain for “Heliotrope Bouquet,” he reprised both the harmonic cadence of Chauvin’s A strain, as well as some of its rhythmic qualities of the habanera, which Chauvin was employing. The habanera is a Latin-American take on a European dance form. It arose in Cuba – the word referring to someone or something from La Habana, Havana – and in Cuba, the habanera incorporated African rhythmic qualities. And all of this multicultural stew of course overlaps the South American tango. This quality of rhythm can be heard in some of Joplin’s “Wall Street Rag” of 1909. But in ’09 he also dove headlong into this realm, composing a work he entitled “Solace” and subtitled “A Mexican Serenade.” And “Solace” is one of Joplin’s masterpieces, a ragtime tango of heartbreaking emotion and nostalgia, especially in its B and C strains. Rifkin gives a remarkably nuanced and impassioned performance of this piece, in which time almost seems to slow to a stop in its C strain, especially in the repeat, as though the heart was too full and required silence to express itself.

Joplin had shown how ragtime, far from being a passing fad in popular music, was in fact a universal sound, a master key that could unlock an array of musical genres – songs, folk dances, waltzes, marches, tangos, and yes, opera. He began sketching out a three-act opera as early as 1907, and by 1909 Joplin was playing for select individuals excerpts of a score he called Treemonisha. The press had gotten wind of it, with one reporter insisting, “I heard the overture; it is great as anything written by Mr. Wagner or Gounod or any of the old masters. It is the original Scott Joplin Negro music. Nothing like it ever written in the United States.”

Joplin was very deliberate about composing a work that, for all its uniqueness, was nevertheless part of the operatic tradition, and he used ragtime to punctuate the action rather than write an entire opera in syncopation. Ragtime serves as his way of delineating racial character among the Blacks in his cast.

Joplin also wrote the libretto of Treemonisha himself, and he took as his subject a community of former slaves in Arkansas in 1884. They live almost hidden from the world, within a thick forest, a geographic isolation that reflects their social isolation from the greater American society as well as the circumscription of their own lives, hemmed in by fear and ignorance, by superstition and a lack of education. The metaphor of course is to the limits of Black integration into American culture and business, into American life, something that could be achieved only through education. The opera’s heroine is a young Black woman named Treemonisha, who has been educated by white people, just as the young Scott Joplin had been first taught music by a white instructor. And through her example, the African Americans in her community are able to overcome the superstitious fears that cause them to be controlled and exploited by others.

It’s very telling that, in Treemonisha, spiritual faith and moral values are highly important and are upheld by the heroine, but organized religion is not. If anything, the church is another face of the same superstitious beliefs that hold them back. Joplin’s opera includes a character he called “Parson Alltalk,” who is indeed all talk, bromides and platitudes, while offering no genuine leadership for his people. Here Joplin is evening the score with Black Christianity, the churches that throughout his lifetime had looked down not just on ragtime – the monster that had emerged from the sinful red-light districts – but on all dancing, all theater. Those forms of expression had been sweepingly rejected, not just by the Black churches but all the Black institutions that sought respectability and assumed leadership, such as the Methodist-run Smith College where Joplin had studied: They specifically forbade dance and theater for their students. It is the heroine Treemonisha, her spirit and her vision, operating outside the church, who confronts the dangers of the criminal elements that undermine her fellow Blacks, and she becomes a leader who advances her people.

Joplin completed Treemonisha in 1910 but was unable to find a publisher – no one would touch a 230-page opera – and so he published the piano-vocal score himself. The following year the American Musician and Art Journal took note of what Joplin had accomplished, insisting, “[H]e has created an entirely new phase of musical art and has produced a thoroughly American opera, dealing with a typical American subject, yet free from all extraneous influence. […] Scott Joplin has not been influenced by his musical studies or by foreign schools. He has created an original type of music in which he employs syncopation in a most artistic and original manner. […] ‘Treemonisha’ is not grand opera, nor is not light opera; it is what we might call character opera or racial opera. […] It has sprung from our soil practically of its own accord. Its composer has focused his mind upon a single object, and with a nature wholly in sympathy with it has hewn an entirely new form of operatic art.”

We’ll listen to some of Treemonisha, but first I want to discuss Joplin’s final piano music. All he published after 1910 are two collaborations with Scott Hayden and two more rags of his own, the last two rags he composed. And they are two of his greatest works: The first, entitled “Scott Joplin’s New Rag,” was composed in 1912; the second is “Magnetic Rag” from 1914. And as I mentioned earlier, they’re both dark pieces, works that reveal a man confronting the abyss. The bitterness and sarcasm of the 1912 rag, its typewriter-like gestures, especially in the A stain, and its unusually quick tempo throughout – Joplin marked the score “Allegro moderato” – these were his way of thumbing his nose at everyone who wanted him to ‘get with the times’ and speed up his music, the people who believed he could just grind out hit after hit after hit, like some factory of ragtime. “Magnetic Rag” is even more bleak, evoking the specter of death.

Almost everything about “Magnetic Rag” is unique in Joplin’s output, starting with the French subtitle he gave it, “Syncopations Classiques.” As in “Scott Joplin’s New Rag,” he again designates the tempo in Italian terminology, indicating his sense of himself as a classical composer, only here the tempo is slower than that of the previous work: “Allegretto ma non troppo” (a little fast, but not too much). The time signature is 4/4, instead of the conventional 2/4 of ragtime music. This is also his only rag in which he employs harmonies in two minor keys, with the A, B, and C strains in the G minor key signature, and the D strain modulating to B flat minor.

That opening A strain has a jaunty, traveling sensation, but the travel becomes a stroll through a cemetery in the macabre B section. The C strain reignites some of the passion of the opening A section, but its rhythmic device of two 32nd notes followed by a quarter or half note keeps sinking in register. Those two 32nd notes can also be heard as an echo of the repeating pair of grace notes from the unsettling B strain. And with his modulation to B flat minor in the D strain, Joplin reaches a terminus, a cessation, with a reiterated high C in its closing bars serving as a death knell.

“Magnetic Rag” also features a striking structural change to the form of classic ragtime, in that Joplin decided not to repeat the A strain in between the second B and first C; instead, he reprises the A strain after the second D – in other words, as the last strain of “Magnetic Rag.” By doing so, he intensifies the tragic perspective of the piece, giving that upbeat opening music a pathos, a farewell quality, which it would not have carried had it been repeated in the middle of the rag. Underscoring this leave-taking is the brief eight-bar coda with its gradually descending melodic line, which ends the piece.

The pianist Joshua Rifkin understood the emotional depth of Joplin’s score, as you’ll hear in his performance of “Magnetic Rag.”

There are two main reasons for the disturbing emotion in “Magnetic Rag,” Joplin’s final piano rag. One was the collapse of his dreams for Treemonisha, because no one would produce or stage his opera. The closest he ever came was a day early in 1915, when he tried to attract backers by renting the Lincoln Theatre on 135th Street in Harlem. The only instrumentalist was Joplin at the piano, accompanying his singers and dancers; there was no scenery, no costumes. He played for a small audience, mostly people he had invited, and nothing came of it.

The other reason for the bleakness you’ve heard is the fact that, by then, Joplin’s health was cratering. Syphilis can remain dormant in a person for a long time, some 20 or 30 years, before manifesting its most destructive effects, the mental and physical deterioration that leads inevitably to paralysis and death. This disease ravaged Joplin’s ability to play the piano. The pianist and composer Eubie Blake recalled meeting Joplin at a reception in Washington, D.C., probably sometime in 1915, where several ragtime pianists were in attendance and performed. Joplin however begged off, insisting that he was ill. Still, people were persistent and Joplin relented and sat down to play “Maple Leaf Rag.” Blake said the performance was “pitiful.” He recognized what the problem was and used a slang term for it: “He was so far gone with the dog, and he sounded like a little child trying to pick out a tune. I hated to see him trying so hard. He was so weak. He was dead but he was breathing. I went to see him after but he could hardly speak he was so ill.”

This is why I have not played for you any of the handful of piano rolls Joplin recorded in 1916: They simply aren’t representative of his music or his own abilities. The best of them sound as good they do only because they were heavily edited. But Joplin’s rhythmic imagination, his sensitive tempi, his expressivity – they’re not there in his piano rolls.

That same year, 1916, Joplin announced to the press that he had completed a musical comedy and was working on a symphony. But none of that music survives – if it was ever composed at all. Whatever work Joplin was still able to produce by then, he soon after destroyed, his fits of depression alternating with paranoid mood swings and fears that his music would be stolen by others. In January 1917 he entered Bellevue Hospital in New York City, and in early February was transferred to the mental ward of Manhattan State Hospital on Wards Island. His descent into madness was followed by speechlessness and paralysis, and on the first of April 1917, at the age of 49, Scott Joplin died on Wards Island.

Before that week was out, the United States entered the First World War; 19 months later the war would end, with over 53,000 American dead. By then the vogue for ragtime music had reached an end. A small coterie of enthusiasts, however, kept the flame alive until the 1970s, when the great ragtime revival began. That movement was launched, as I discussed earlier, by Joshua Rifkin’s Nonesuch recordings. Another crucial figure was the composer, conductor, historian, and educator Gunther Schuller. When the revival reached its peak, full-scale productions of Treemonisha became the crowning events, with performances in Atlanta and Washington, D.C., and finally the Houston Grand Opera in 1975, with Schuller’s sensitive orchestration of Joplin’s piano score. He said, “I wrote as closely as possible to what Joplin would have done in terms of the instrumentation and abilities of pit bands of his day. I tried to keep in mind what Joplin would have had in his ear.”

That production from Texas, the state where Joplin was born, then relocated to New York and ran on Broadway for about nine weeks. This successful realization of Treemonisha led to Joplin being awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1976, our bicentennial year.

Joplin’s widow, Lottie Stokes Joplin, gave an interview in 1950, in which she asserted, “You might say he died of disappointments, his health broken mentally and physically. But he was a great man, a great man! He wanted to be a real leader. He wanted to free his people from poverty and ignorance and superstition, just like the heroine of his ragtime opera, Treemonisha. That’s why he was so ambitious; that’s why he tackled major projects. In fact, that’s why he was so far ahead of his time … You know, he would often say that he’d never be appreciated until after he was dead.”

Whenever I hear someone say that Scott Joplin was ahead of his time, I always think of the great early modernist composer Edgard Varèse. He insisted that artists are never ahead of their time; the problem, he said, is that most audiences are behind their time.

But Lottie Joplin was quite right when she insisted that Joplin was seeking to educate and elevate people – his people and all people. I want to leave you with a video of the finale of Treemonisha, from its Houston production. The closing number is the celebration of Treemonisha as the leader of her people, and she leads them in a dance, called “A Real Slow Drag.”

This is Joplin’s final attempt to educate his audience, so people would not be taken in by the high-speed distortions of ragtime, which had been promoted by Tin Pan Alley; so they would understand that the essence of this music is in the stateliness of its tempo – that’s where the power, the emotional depth, the dignity, the nobility of the music resides. “Slow” is the last word sung in the opera, with the entire company singing:

Dance slowly, prance slowly,

While you hear that pretty rag.

Dance slowly, prance slowly,

Now you do the real slow drag.

Walk slowly, talk lowly,

Listen to that rag.

Hop,

And skip,

Now do that slow,

Do that slow drag.

Slow.

(This lecture was first given at the main branch of the San Francisco Public Library in January of 2025. Special thanks to Michelle Jeffers, Sam Genovese, Mike, Kenny, and all the wonderful people at SFPL!)

SOURCES

“I am deeply interested in this man”

James Haskins and Kathleen Benson, Scott Joplin: The Man Who Made Ragtime. New York: Doubleday, 1978, p. 113.

“A very dear friend of mine and a marvelous pianist”

Alan Lomax, Mister Jelly Roll, second edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973, p. 121.

“He had lots of original tunes of his own”

Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, They All Played Ragtime, fourth edition. New York: Oak Publications, 1971, pp. 56–57.

“I heard the overture”

Edward A. Berlin, King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 191.

“[H]e has created an entirely new phase of musical art”

Berlin, King of Ragtime, pp. 201–202.

“He was so far gone with the dog”

Berlin, King of Ragtime, p. 236.

“I wrote as closely as possible to what Joplin would have done”

Haskins and Benson, Scott Joplin, p. 15.

“You might say he died of disappointments”

Haskins and Benson, Scott Joplin, pp. 195–196.

Link to:

Music: Lectures: Contents

For more on Scott Joplin, see:

Music: SFCR Radio Show #27, 20th-Century Music on the March

For more on Scott Joplin and Gunther Schuller, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

For more on Gunther Schuller, see:

Music: SFCR Radio Show #18, Gunther Schuller and Pierre Boulez at 90

And here’s a video of the January 2025 lecture (musical examples have been deleted due to rights issues):