My Experiences of Surrealism in 20th-Century American Music

The title of this lecture is “My Experiences of Surrealism in 20th-Century American Music,” and I’d like to begin in France in 1853, with the composer Hector Berlioz. That was the year he began a decade-long stint as a music critic for the Paris newspaper Journal des débats – it was a regular gig and he needed the money. He also wrote for Gazette musicale and other publications around this time, the middle of the nineteenth century, and he has left us a very interesting account of a piano competition that was held at the Paris Conservatory. According to Berlioz, thirty pianists showed up to play the competition piece, which was the G-minor concerto of Felix Mendelssohn. And they ran into a big problem after the last contestant, because the piano started playing the concerto all by itself. People were appalled of course, but no one was able to make it stop. They had to summon the manufacturer – it was an Érard and Pierre Érard himself showed up. But it was totally futile, nothing he did made any difference. He even tried sprinkling holy water on it but it kept right on playing the concerto. They removed the keyboard, while the keys were still dancing, and flung it into the courtyard – still didn’t stop. Finally they had to take an ax to it and incinerate the remains. Berlioz insisted, “There was no other way to loose its grip. But after all, how can a piano hear a concerto thirty times in the same hall on the same day without contracting the habit of it?”

None of this should surprise us, our music is filled with accounts of unusual and aggressive piano behavior. The piano is a high-strung instrument, after all. You’ll hear pianists talk a lot about piano action, well that takes a wide range of forms, and some of them can be quite dangerous. It was a piano that left Robert Schumann with a permanently disabled right hand, ending his career as a recitalist. Another piano almost did something similar to Alexander Scriabin. He was more fortunate, his right hand recovered, but the funereal sadness and resignation that end Scriabin’s First Piano Sonata from 1892, his Opus 6 – these are rooted in his despair that he’d never be able to concertize again.

Pianists as different – and as legendary – as Erwin Nyiregyhazi and “Blue” Gene Tyranny have left keyboards stained with their blood. (There’s a video of “Blue” playing and leaving this trail, and they write on the video alongside the image, “He only plays the sharp keys”!) Youtube has a clip of András Schiff insisting that when he plays Béla Bartók’s Second Piano Concerto, “I usually end up with a keyboard covered by blood.” If you Google “blood on piano keys,” you’ll see photos that have gone viral, from a competition held last year in Cincinnati. A young woman played the Bartók Sonata for Piano, and you’d think it bit off one of her hands, the keyboard looks like the floor of an abattoir. It took them fifteen minutes to clean the blood off it before someone else could play.

La Monte Young helped energize the Fluxus movement back in 1960 by writing his series of Compositions, which included Piano Piece for David Tudor #1, where the performer gives the piano a bale of hay and a bucket of water. Audiences laugh of course, because people know that pianos are carnivorous. The keys look like teeth for a reason.

Still, I do not want to overemphasize the piano’s appetite for blood. A friend of mine, an American composer, had two pianos in his studio, and they never harmed him. He told me that they terrorized his young son, frightened the child so badly that he ran out of the studio in a panic. But they never harmed my friend. But sometimes one of them would start behaving like a Spanish guitar. I’m not making any of this up. Listen to a recording of his Study No. 12, made in his studio in 1988. There are no tape manipulations, no computer tricks – hand to G-d, no one is playing that piano.

My friend’s name was Conlon Nancarrow. Are any of you at all familiar with his music?

He was born in Texarkana, Arkansas, in 1912 and was mostly self-taught as a composer. He had studied the trumpet and was playing jazz in the early 1930s. After taking a semester at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, he was in Boston by 1934, where he studied with Roger Sessions and found encouragement from Nicolas Slonimsky and Walter Piston. In 1935 Nancarrow composed a Toccata for violin and piano and a Prelude and Blues for piano, but his quick tempi and jazz-inspired rhythms were so demanding that the pieces had to be arranged for piano four-hands when they were premiered in 1939.

Nancarrow went to Spain in 1937 to fight with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, and the following year Slonimsky published the Toccata, Prelude, and Blues in a New Music Edition. Aaron Copland praised those scores in Modern Music magazine, and he got Nancarrow to write for Modern Music after his return from Spain in 1939. But the U.S. government refused to issue Nancarrow a passport because of his Communist affiliations, so he left the States and settled in Mexico City in 1940, becoming a Mexican citizen in 1955.

Strains of jazz and blues characterize most of Nancarrow’s music in the early 1940s, such as the Septet, Sonatina for piano, and String Quartet No. 1. But his tempi and rhythms became even more challenging, and performances were few and unsatisfactory. He wanted to delve into even greater extremes of rhythm and tempo, and so he followed a suggestion that Henry Cowell had made in his book New Musical Resources, published in 1930 but written mostly in 1919. Cowell had been deriving very unusual rhythmic structures from intervals in the harmonic series, but they were monstrously difficult to play – his Two Rhythm-Harmony Quartets of 1919 would not be performed until 1975. So Cowell pointed out in New Musical Resources, “Some of the rhythms developed […] could not be played by any living performer; but these highly engrossing rhythmical complexes could easily be cut on a player-piano roll. This would give a real reason for writing music specifically for player piano.”

Conlon Nancarrow told me that he read New Musical Resources around 1939, 1940 and that it was very important to him. “From the time I started composing, I’d always had this thing of working from temporal matters, rhythm and so forth, and this thing sort of grew. By the time I saw Cowell’s book, it was just a big push ahead.”

At first Nancarrow tried to build a percussion machine after the principle of a player piano, using a pneumatic device to read holes on a paper roll and operate beaters to strike drumheads and wood blocks. But it never worked properly, so in 1947 he bought a player piano and a roll-punching machine, and he never looked back. He created a series of works, Studies for Player Piano, from the late 1940s until his death in 1997, at his home in Mexico City, at the age of 84.

What I played for you was his Study No. 12, composed around 1950 – he was rather casual about dating the Studies. In the 1950s and ‘60s, Nancarrow’s music was promoted by composers as different as Elliott Carter and John Cage; in the 1970s and ‘80s, he was championed by younger composers such as James Tenney, Peter Garland and Charles Amirkhanian. The Studies were eventually heard and appreciated worldwide, and Nancarrow was lionized, touring the States and Europe in the 1980s. Pianists such as Yvar Mikhashoff began performing certain Studies, and Studies were arranged by Mikhashoff and others in versions for piano four-hands or for chamber ensembles. The composer and inventor Trimpin digitalized the Studies into MIDI-information, so a computer could drive his vorsetzer, a device placed on a piano keyboard, which plays the Studies “live.”

I first met Conlon at his home in Mexico City in 1980, and saw him in his visits to the States in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and we corresponded and remained friends right to his final years, and I can tell you, from my experience, that he didn’t have any particular feelings for surrealism when he was creating his music – that topic never came up in our conversations. I did ask him once if he’d ever met the filmmaker Luis Buñuel. Conlon had moved in circles of creative people in Mexico for many years, and Buñuel did brilliant work there during the 1950s and ‘60s: Los Olvidados, El, The Exterminating Angel, Simon of the Desert. Conlon told me yes, he’d met Buñuel once at some gathering, and he said that he was talking with Buñuel for a while, in a perfectly normal and genial way, until it dawned on him that Buñuel was deaf as a post and hadn’t heard anything of what Conlon was saying to him.

Permit me to digress here for a moment. I find that story very interesting, one could argue that Buñuel was using his disability to, if you like, surrealize his environment. Albert Camus wrote in “The Myth of Sisyphus,” “Men too secrete the inhuman. At certain moments of lucidity, the mechanical aspects of their gestures, their meaningless pantomime makes silly everything that surrounds them. A man is talking on the telephone behind a glass partition; you cannot hear him, but you see his incomprehensible dumb show; you wonder why he is alive.” People become absurd – meaningless vessels waiting for your imagination to attribute meanings to them. And of course the origin of the word “absurd” is related to the Latin surdus, deaf.

To resume about Conlon Nancarrow: He was also friends with the Mexican artist and architect Juan O’Gorman, and after Conlon married Yoko Sugiura in 1972, he expanded his house working with O’Gorman, who had created a stone mosaic for the exterior of Conlon’s older, smaller house in the 1950s. The ‘70s design of the new house was O’Gorman’s wedding present, with several of the exterior walls covered by colored-stone mosaics. And of course by that time O’Gorman had stepped away from the modernist functionalism he had once embraced – that was how O’Gorman, when he was still in his twenties, had designed a house and studio for Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in the early 1930s. But later in his life O’Gorman was drawing inspiration from Antoni Gaudí and Frank Lloyd Wright, and he was working in vernacular and surrealist idioms – a combination that categorizes his mosaic illumination of Conlon’s home and studio. So you could say quite literally that Conlon lived within and was surrounded by surrealist imagery.

But his interest with the Studies for Player Piano was the pursuit of extreme and unusual tempi and rhythmic relationships. Only a few of the Studies bother to evoke other forms of music the way No. 12 does. Still, I think it’s useful to start this discussion of surrealism in American music with Nancarrow and that piece, because one aspect of the surreal in music is the ability to distort and transform and confound our sense of what you could call “reality” in music, to shock the mind awake, and to pursue a new and deeper understanding.

And hearing a piano do that, definitely has such an effect! But despite Nancarrow’s ascendancy, few composers have attempted the work of making music for player piano. That instrument has been superseded by developments in electronic- and computer-music technologies – which Nancarrow would have used, had it been available in his day. Luckily for us, he didn’t wait.

Nancarrow is one of the rare examples of surrealist qualities in later modernist music in America. This notion of distorting musical reality has its roots in early modernists such as Erik Satie or Charles Ives or George Antheil, and there are elements of it to be found later in Nancarrow. Nevertheless, the surrealist sensibility in music is basically a postmodern phenomenon. That’s partly because technology needed to catch up in music, and provide a greater plasticity of sound through computers and sampling. But it’s not that simple, there’s more to it than that. I’ll be playing you some music by The Residents, pre-computers and -samplers, which is truly surreal.

And I’ll just mention here an instance of that plasticity being employed without surrealist implications. One of the great late-modernist composers was Pierre Boulez, who passed away earlier this year at the age of 90. His electro-acoustic work … explosante-fixe …, composed in 1993, is scored for flute with live electronics, two flutes, and chamber orchestra. It uses electronics over a wide spectrum of sound, sometimes mimicking instruments, sometimes purely electronic. But he’s doing these things in pursuit of certain pitch and rhythmic and timbral relationships. Despite his fondness for setting texts by the surrealist poet René Char, Boulez dismissed surrealism repeatedly in his writings and lectures of the 1950s and ‘60s, calling it “dead” and a “footnote” and “a lot of fuss about nothing,” and I doubt he ever looked back again.

So let’s stop here for a moment and look at some ideas and dates concerning modernism and postmodernism. And the first thing you have to keep in mind is that, as compositional periods, late modernism and early postmodernism overlap. When I think back, it seems like in the 1960s and ’70s, everyone used to talk about the drastic change in music, which had occurred with the advent of the early modernists in the 1900s, teens, and ‘20s. But from the distance of our hundreds and teens, it seems perfectly clear that the greatest and most profound shift in imagination for Western music occurred over the second half of the twentieth century.

Yes, in the first half of the twentieth century, modernism introduced shocking new liberties in harmony, rhythm, and tonality. But the view modernism held of what music was and what composition was – the attitudes, the definitions, the conceptualizations – these were still fundamentally an extension of classical and romantic mind-sets. What modernism did was keep the game going by extending the goalposts well into the stands, achieving coherence and beauty and expressivity through dissonance, polyrhythm, and atonality. Postmodernism takes music out of the stadium altogether.

Modernism revealed the arbitrary nature of traditional harmony, rhythm, and tonality, which had for so long been taken by so many as gospel. Postmodernism can be seen as a reaction to and a critique of modernism, turning modernism’s x-ray back upon itself by exploring modernist freedoms without relying on modernist conceptualizations or materials. Modernism shattered traditional music into an array of individualized styles and methods; postmodernism develops techniques to appropriate, deconstruct, and recontextualize what is available today, when virtually any and all the music of the world can be heard.

A postmodern composer isn’t choosing between traditionalism and modernism, not when the materials of jazz, blues, rock, pop music, folk music, world music, noise, electronics, and natural and environmental sound can also be employed, either transformed or in quotation – but employed without necessarily pursuing their genres’ conventions or conceptualizations. This postmodern openness has vitalized numerous areas of musical exploration for more than half a century: minimalism, multimedia, multiculturalism, instrument building, alternate tuning systems, extended performance techniques, theatrical music, spatial music, ambient music, computer music, sampling, free improvisation – and surrealism.

It’s very easy to trace the musical evolution from Wagner to Bruckner to Mahler to Schoenberg to Webern to Babbitt. The lineage is crystal clear. So too is the evolution from Debussy and Ravel to Stravinsky to Messiaen to Boulez. Postmodernism represents a true break in the concert-music tradition, and it begins appropriately enough not in Europe but in America, with the music of Harry Partch and John Cage. Nothing Schoenberg wrote will lead you to indeterminate composition; Cage studied with Schoenberg, and yet you cannot draw a straight line from anything in Schoenberg’s music to Cage’s Imaginary Landscape No. 4 for 12 radios or to 4’33”, a score in which no sound is performed. By the same token, there’s nothing in Stravinsky’s music that leads you to the just-intonation tunings and new instruments of Harry Partch. Both Cage and Partch represent a sweeping rejection of how music had developed. Each was doing important work by the 1930s, but it was in the ‘50s that they reached a whole new level of expression – Partch through music theater and Cage through indeterminacy – and their impact has been indelible, irreversible. And let me just add here that postmodern attitudes also took root in other forms of Western music by the 1960s, transforming jazz with the music of Sun Ra and expanding and redefining rock with the music of The Beatles – both artists have their own surrealist qualities too.

John Cage of course is particularly relevant to this discussion, and I know you’ve been examining his work from the perspective of surrealism. So I’d like to focus here on one of Cage’s students – and the only American composer I’m discussing today, who I never met. He’s a very important figure yet he tends to be overlooked. His name was Richard Maxfield, and you can see this shift in sensibility from modernist to postmodern in his music. In the 1960s he was one of the first to bring electro-acoustic music into surrealist territory, which here in the States put him ahead of the curve yet again – in 1959 at the New School for Social Research, Maxfield had already become quite likely the first person in America to teach a course in making music from electronically generated sound.

Maxfield was born in Seattle in 1927, and he studied in the States with Roger Sessions, Milton Babbitt, and Aaron Copland, and in Europe with Ernst Krenek, Luigi Dallapiccola, and Bruno Maderna – some of the great modernist composers of his day, and Maxfield’s early instrumental music was mostly serial. But by the late 1950s he was attracted to ideas of indeterminate composition, which he encountered through some of the great postmodern composers of his day: Christian Wolff, David Tudor, and John Cage, and Maxfield studied with Cage at the New School in 1958.

He was also drawn to electronic music and became one of the first American composers to build his own equipment for the electrical synthesis of sound. He produced landmark compositions, starting in 1959 with Sine Music – which he also called A Swarm of Butterflies Encountered over the Ocean, a beautiful surrealist image. But he was equally pioneering in tape music. Maxfield created an array of notable works including Cough Music from 1961, made from the sounds of people coughing at concerts. He would typically combine deliberate methods of recording and processing sound with random selections in editing – he often kept his tape-music pieces in fluid states, playing different versions in concerts.

So in the early 1960s, Maxfield was already seeing tape music as something of a plastic, playable medium for public performances, and that sensibility led him to break new ground in electro-acoustic music, starting in 1960 with his piece Wind for Terry Jennings; the following year he’d create Piano Concert for David Tudor and in 1962 Perspectives for La Monte Young. Maxfield would tape each of these composer/musicians performing and then electronically alter the tapes to create new music with which he would accompany them in live performance.

Now, David Tudor had worked with Cage for years and was employing novel acoustic and/or electronic sound inside and outside the piano in realizing such Cage classics as Variations I, Concert for Piano and Orchestra, and Cartridge Music, so Tudor totally went out there for Maxfield. Playing the piano in Piano Concert for David Tudor, Tudor is manipulating chains inside the piano, letting a gyroscope spin on the strings, dumping in little plastic tiddlywink chips, all as Maxfield is enveloping him with a three-channel tape set-up.

That such activity even constitutes a piano concert is proof enough that a surrealist attitude is at work. I’m sure you’re all familiar with this, but I’d like to remind you of that wonderful quote of André Breton: “Everything tends to make us believe that there exists a certain point of the mind at which life and death, the real and the imagined, past and future, the communicable and the incommunicable, high and low, cease to be perceived as contradictions. Now search as one may one will never find any other motivating force in the activities of the Surrealists than the hope of finding and fixing this point.”

So of course you get Lautréamont, “the chance encounter on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.” And you get Maxfield, the chance meeting on tape of tiddlywinks and chains inside a piano. But that’s the great thing about art, shocking the mind awake is how art is supposed to work. A sewing machine and an umbrella may be inadequate tools for dissecting a cadaver, but whether it’s chains on strings or fingers on keys, with music there’s no difference, they’re not contradictory actions, music is still being made, and you get to listen.

You see, this is why Boulez had to reject surrealism, saying of “The surrealist practice of collage […] this poetics without choice has worn thin, the lack of purpose in the selection of sound material produces an anarchy which, however agreeable it may be, is fatally detrimental to composition. To lend itself to composition, musical material needs to be sufficiently flexible, susceptible to transformation, and capable of generating and sustaining a dialectic.”

Choice, purpose, dialectic. This pitch has a frequency which is different from the frequency of that pitch; this dynamic level is loud and that one is quiet; that’s a piano playing, this is a tuba; that sound lasted that long and this sound is lasting this long.

This cannot be that. A cannot be B; A has to be A and B has to be B. They collide, sparks ensue, changes and transformations, AB, BA, Ab, bA, aB, Ba, and you follow all those As and Bs, and that’s music. That was music to Haydn and Mozart and that was music to Schoenberg and Stravinsky and that was music to Babbitt and Boulez.

What’s disadvantageous about this approach, what those of you who compose need to be concerned about, are the limitations – artistic, conceptual, experiential – the limitations that arise due to the fact that A is B. That’s a fact, A is B. Yes there is Yin and yes there is Yang, but they arise together from a single source, and that unity is a mystery, the deepest of all mysteries. The conditioned mind works to ignore that mystery, believing that you can best navigate through the world by agreeing that reality stops at contradiction, that this is not that, that here is not there and you are not me and A is not B. Surrealism brings that mystery to the fore, and seeks to break down conditioned ways of thinking and feeling, usually by drawing more directly on material from the unconscious.

Maxfield clearly understood that; listen to the Piano Concert for David Tudor from a 1961 performance, and I think you’ll hear what I mean.

This approach of working collaboratively with instrumental musicians to create electro-acoustic compositions was also employed by Maxfield with ensembles, as in his 1962 Toy Symphony. There was a minimalist sensibility to how he shaped the static sounds in his electronic music, and he was also involved during this time with the Fluxus composers and their performances. He was a curator of some of their performances, and it was probably 1961 when the Fluxus musicians were playing a piece by Maxfield called Concert Suite from the Ballet “Dromenon” and La Monte Young, a co-curator with Maxfield, decided to start playing a piece of his own, his Composition 1960 #2, which calls for the performer to “build a fire in front of the audience,” and so he set his violin on fire.

In 1966 Maxfield left New York City to teach at San Francisco State College. He relocated to Los Angeles in 1968, but the following year, tragically, he took his own life there at the age of 42. But Maxfield’s approach to creating electro-acoustic music thrived. Pauline Oliveros began amplifying and expanding her accordion in 1966 and soon was using elaborate tape delays and mixing assistance. Now, her performances with the expanded accordion are clearly relevant to this discussion, but it’s not so much a surrealist sensibility at work in her case, it seems to me; or rather, her focus is that “certain aspect of the spirit,” which Breton described, she’s attempting to locate that point where contradictions vanish, by working directly with meditation and consciousness and minimalist processes and improvisation, which sometimes lend her music surrealist qualities. That’s how you get the slow, majestic, astonishing, continuous transformation of sound in a work like her Crone Music for expanded accordion, or shocks like the sudden appearance of Puccini in her classic electronic improvisation Bye Bye Butterfly.

Back in 1960 Oliveros and Ramon Sender formed Sonics, a center for tape and electronic music, which was then part of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Sonics grew into the San Francisco Tape Music Center by 1962 – Oliveros was in Europe at the time, and Sender teamed up with the composer Morton Subotnick to form the Center. And in the 1970s, it was Subotnick who took electro-acoustic music quite deliberately into the realms of surrealism, starting with his ghost scores.

He was born not far from here, in Los Angeles, in 1933. (Subotnick just turned 83 earlier this month.) He had played clarinet in the Denver Symphony Orchestra while attending the University of Denver, and later he went to Mills College and studied composition with Leon Kirchner and Darius Milhaud. By the beginning of the 1960s he was creating tape-music scores for theater and dancers, and composing multimedia works that combined tape music, film, lights, instrumentalists. A few years later, by the mid 1960s, he was in New York City supplying electronic music and more for the legendary discotheque the Electric Circus. By then Subotnick had also gotten the commission from Nonesuch Records to create his landmark electronic work Silver Apples of the Moon, the first electronic score commissioned for recording, which Nonesuch released almost 50 years ago, in 1967. That’s what put Subotnick on the map internationally among the forefront of electronic-music composers, and that music is derived from his work at the Electric Circus. But the Electric Circus was also something Subotnick actually helped conceptualize and create, right from its formation, and working there enabled him to take not just his electronically synthesized music, but his tape and multimedia composition as well, to a whole new level – a level of relevance to our topic of surrealism. This is how he described to me his work at the Electric Circus:

“You’d be dancing and the room would get dark and then all of a sudden a whole side of the room would come up with purple and black light, and there’d be a fire eater and music – maybe four or five or six minutes of no dancing, just images of people flying across the ceiling. The whole evening was developed to reach this peak of things: You would see 25 people in black light, suddenly eating bananas, just standing there one after another, and then they’d disappear. It was really quite remarkable. Then they got nervous and wanted people to dance all the time, so they got rid of all the interludes and all the other stuff.”

This situation of the unstable and unknowable environment, prone to inexplicable paroxysms and redefinitions and transformations, is very much the stuff of dreams and of surrealism, from Lewis Carroll to Salvador Dalí. It also characterizes Subotnick’s ghost scores. These works are electro-acoustic compositions, in which musicians are accompanied by electronic sound that is generated from their own playing in real time, created by a tape recorder with outputs attached to different modules to alter their sounds. Subotnick’s first ghost-score piece was in 1977, Two Life Histories for clarinet and male voice, followed later that same year by Liquid Strata for piano. I’m going to play some of the piano piece for you, but first I want to share with you Subotnick’s sense of what was happening in these scores. When I asked him if, with the ghost scores, we’re hearing a duet or a single sound source, he told me, “My vision of it is that we hear a single sound, that we don’t know the difference.”

Unlike the electro-acoustic music of, say, Milton Babbitt or Mario Davidovsky and his Synchronisms series, Subotnick was very much concerned with dissolving the distinctions between instrumental and electronic media – an approach much closer to Oliveros and the expanded accordion. Now, as we’ve heard, that approach also characterized Richard Maxfield’s electro-acoustic music – blurring the listener’s sense of reality in terms of what was being played live by the soloist and what sounds were manipulated tape. But the very nature of Maxfield’s pieces – for Terry Jennings, for David Tudor, for La Monte Young – also pushed those works into the realm of not just duet but, if you like, concerto. Subotnick however, working 15 years later, was able to achieve a remarkably subtle and pervasive transformation of instrumental sound, making the electronic sound not an accompaniment or a backdrop, but rather an intimate part of the fabric. And the effect of sustaining this hybrid takes us back to the fluid space of the Electric Circus. Subotnick told me:

“I had imagined the ghost pieces as a fabric, sort of like an architectonic space where the sound becomes a function of whether there’s oxygen or helium, say; whether there’s sand or hollow walls or water – that different physical mediums will effect how sound is heard, so that you were playing the piano in a world where there was no cause and effect, and suddenly half the room becomes absorbent and the other half becomes reverberant, or the room changes from helium to some other mixture so that the pitches actually weave and change. That was the sense that I had of these pieces: where the physical nature of the stage, acoustically, is changing, so that we have the sense that the stage isn’t what we expected. My first image was of the old Hollywood movie where the composer’s the pianist and the building is burning down while he’s playing his last concerto! For me, it’s antithetical, it doesn’t mean anything, if you hear the player and it’s normal. That’s impossible in this world that I’ve created. The idea is that it is just the piano, but the piano is doing what a piano can’t do, which is changing pitch and changing quality throughout the piece.”

To maintain this impossible piano, Subotnick needed to compose not a duet but a solo – “the blend is what I expect,” he insisted to me. Creating that kind of unity, however, involved him in a funny contradiction. With these pieces, rather than rehearsing and rehearsing the instrumentalists with the electronics, Subotnick found he got the best results by bringing them together “as late as possible. Like the man in the burning building, they have to know what they’re doing but they should be unaware of the result, so that they are playing masterfully without being affected by the result. The ideal would be that they never played with it before, but that’s almost impossible because you’ve got to do something with it. But my recommendation is always to do it as late as possible; to make the piece project as a piece, so that’s what you feel when you’re doing it, and never to have monitors, so the speakers are in front of you and you’re very unaware of the result.”

He wasn’t trying to change the musician’s relationship with the instrument, he was trying to change the audience’s relationship with the instrument. He told me, “it’s this world we’re looking into; it’s not our world, it’s this person who’s in this world and is unaware of what we’re hearing.”

Subotnick called his three-part Liquid Strata for piano and ghost electronics “a romantic, poetic response to the profound scientific insights about fundamental realities of nature as enunciated by Newton.” This piece is also increasingly romantic, culminating in its last movement with the piano quoting Chopin. In the first movement, Subotnick creates some of his most subtle and unusual transformational effects with the piano. You can also hear the pianist reciting some quotes from Isaac Newton – and getting ghosted vocally as well. As in Maxfield’s Piano Concert for David Tudor, the pianist of Liquid Strata also begins playing inside the piano.

Subotnick did a series of ghost scores into the early 1980s, usually working with a solo instrumentalist – clarinet in Passages of the Beast, viola in An Arsenal of Defense, cello in Axolotl, one of his finest works. (An axolotl is an amphibian found in Mexico, it’s known also as a walking fish, because of its fishlike appearance, even though it’s actually a salamander – you can see why this species confusion would appeal to Subotnick in this music.) Axolotl can be performed just by a cellist or by a cellist accompanied by a chamber orchestra. Other Subotnick pieces that play a “ghosted” soloist against a non-ghosted ensemble include Parallel Lines for piccolo with nine instruments and After the Butterfly for trombone with septet.

But by the early 1980s Subotnick was also branching out into other electronic means of interacting with live musicians, which of course led him to computers. He composed Ascent into Air for chamber ensemble and computer, using the computer at IRCAM, as early as 1981, drawing upon techniques and effects he had generated with the ghost scores.

And of course the computer became increasingly fundamental to Subotnick’s work in this realm, displacing the tape-based ghost scores. And he created three major works, all of which he considered “imaginary ballets”: The Key to Songs in 1985, And the Butterflies Begin to Sing in 1988, and All My Hummingbirds Have Alibis in 1991. Each one combines smaller chamber groups with increasingly sophisticated computer technology. And in all of these works, Subotnick was involved with the art of surrealist master Max Ernst, particularly Ernst’s great collage novels.

The Key to Songs is scored for two pianos, two percussionists playing mallet instruments, viola, cello, and computer, although the interactive properties of the computer were not very advanced in 1985, and it mostly runs sequences. The title is from Ernst’s Une semaine de bonté, “A Week of Kindness,” from 1934. The final day, Saturday, which is dominated by images of women falling through space, has as its designated element la clé des chants, “the key to songs.”

And the Butterflies Begin to Sing, for string quartet, string bass, MIDI keyboard, and computer, involves a greater interactivity from the computer, with Subotnick creating musical equivalents of some of the collages in Ernst’s 1929 La Femme 100 Têtes. That title is a pun, written as la femme, then the numeral 100, then têtes, playing on C-E-N-T, cent, 100, which sounds like sans, S-A-N-S, without. So you’ll see the title translated as “the hundred headed woman,” “the hundred headless woman,” “the woman without heads.”

In All My Hummingbirds Have Alibis, for flute, cello, MIDI keyboard, MIDI mallets, and computer, the computer is totally interactive and doesn’t run any sequences; instead it is continuously responding to what the musicians are doing. Besides transforming the instrumental sounds and controlling the mixer and the amplification, the computer is also generating its own sounds, as well as sampled voices that include Subotnick and his wife, the composer and singer Joan LaBarbara. And their text is by Max Ernst from his 1930 Rêve d’une petite fille qui voulut entrer au Carmel – commonly translated as “A Young Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil.” But while the computer is providing the voices, the vocal lines are being played by the musicians at the MIDI keyboard and MIDI mallets, using the INTERACTOR software Subotnick designed with Mark Coniglio.

Subotnick became increasingly involved with theater and multimedia works, but other milestones in his career include A Desert Flowers in 1989, for orchestra and computer, where the conductor uses a computer-modified baton that controls the electronics, and Five Scenes from an Imaginary Ballet, from 1992, the first work conceived specifically for CD-ROM.

And now that we’re talking about composing with computers, I’d like to turn to the music of Charles Dodge, who carved out a still unique place for himself by synthesizing human speech. He was born in Ames, Iowa, in 1942, and in the early 1960s he came East and studied with Gunther Schuller at Tanglewood and with Jack Beeson, Otto Luening, and Chou Wen-chung at Columbia University; he also studied with Darius Milhaud in Iowa and in Aspen, Colorado. But it was at Columbia that Dodge studied electronic music with Vladimir Ussachevsky; at Princeton he studied computer music with Godfrey Winham. This is the mid 1960s, they were still punching IBM cards in order to work with computers then. You’d spend hours punching cards and then you’d feed them into the computer at Princeton and find out if you’d made any mistakes. If you did, you’d go back and fix the cards and do it again; if you didn’t, you could then arrange for the digital-to-analog conversion of all your computer information, which was done by other machines at the Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey.

It was a complicated, tortuous process, but it rapidly streamlined and by the 1970s Charles Dodge was sitting in his own studio, typing instructions directly into his computer and hearing the results. And what freed him as a composer was the results he was getting with speech. A speaking voice is recorded, its waveform is converted into digital information that’s fed into the computer, and an analyzer provides a set of values, or parameters, for the voice’s frequency content and resonance structure for every one-hundredth of a second. With that information, the computer can resynthesize the speech, altering whatever parameters you designate as you go along. So unlike tape, the computer can speed up the voice without raising its pitch, or alter the pitch without changing its speed.

Dodge’s first work in this vein was a setting of short poems by Mark Stand, the four Speech Songs, created in 1972 at Bell Labs. Dodge told me that “The Speech Songs […] used for the first three songs a technique of speech analysis called formant tracking. The formant tracking necessarily results in mechanical-sounding speech. The fourth Speech Song sounds extremely natural, due to a brilliant breakthrough in speech analysis on the part of Vishnu Atal, a researcher in speech at Bell Labs. Since that time, I have created my own speech-synthesis and speech analysis-system at Columbia, in which the speech quality is extremely natural. With the new system, it’s possible to analyze female voice as well as male voice, and to change the pitch of the synthetic voice over a very wide range without destroying the intelligibility. […] Formant tracking would work only on male voice. It was a feature of the technique.”

You see how constricted the playing field was at the dawn of this technique over 40 years ago. And yet within those limitations Dodge created four short pieces that seem to explode with possibilities and unpredictabilities – humor too. Dodge has written, “Laughter at new music concerts, especially in New York these days, is a rare thing; and it has been a source of great pleasure to me to hear audiences respond with laughter to places in all four of the Speech Songs.”

Dodge’s speech-synthesis music became increasingly sophisticated and imaginative over the 1970s with The Story of Our Lives and In Celebration, two other Mark Strand settings, and Cascando, a realization of Samuel Beckett’s radio play. One of Dodge’s funniest works is the 1980 Any Resemblance Is Purely Coincidental, where a pianist performs with a synthesized voice derived from a recording of Enrico Caruso. One of Dodge’s most beautiful works is The Waves for soprano and tape, from 1984, which sets a text by Virginia Woolf and has only subtle synthetic-speech effects woven into the electronic sound that accompanies the singer.

But one thing The Waves does, in an eerie and effective way, is create illusions of space, spatial relationships. That has also been a characteristic of Dodge’s speech music, and I think you could hear him moving in that direction even in something as early as the Speech Songs. Morton Subotnick – whose wife, the soprano Joan LaBarbara, has made a fantastic recording of The Waves – has also been very concerned with creating impressions of changing spatial dynamics in his electronic music, as you can gather from the ghost scores; in fact he told me that idea of using electronic sound to create a sense of space, “That to me was finally the essence of what the whole medium was.” So he jumped at the chance to do the electronic recording Touch in quadrophonic sound, even though he ultimately resigned himself to working within a proscenium format rather than a quadrophonic one, due to the realities of recordings and home listening.

The fluidity of space in the music of Dodge and Subotnick, the feeling that space is as plastic and pliable as the sound of the voice or an instrument, creates a deeply surreal situation. And even though Dodge, unlike Subotnick, hasn’t overtly dealt with surrealist imagery, his music is one of the most striking in its capacity to transform the familiar and shock the mind, obliging you not just to listen to but to relate to, to empathize and identify with a voice that is neither human nor synthetic, but an unstable amalgam of the two.

All the themes that we’ve been examining – surrealism, transforming sonic reality, electro-acoustic composition, creating space, humor – they all come together in the music of The Residents, which I’d like to turn to now.

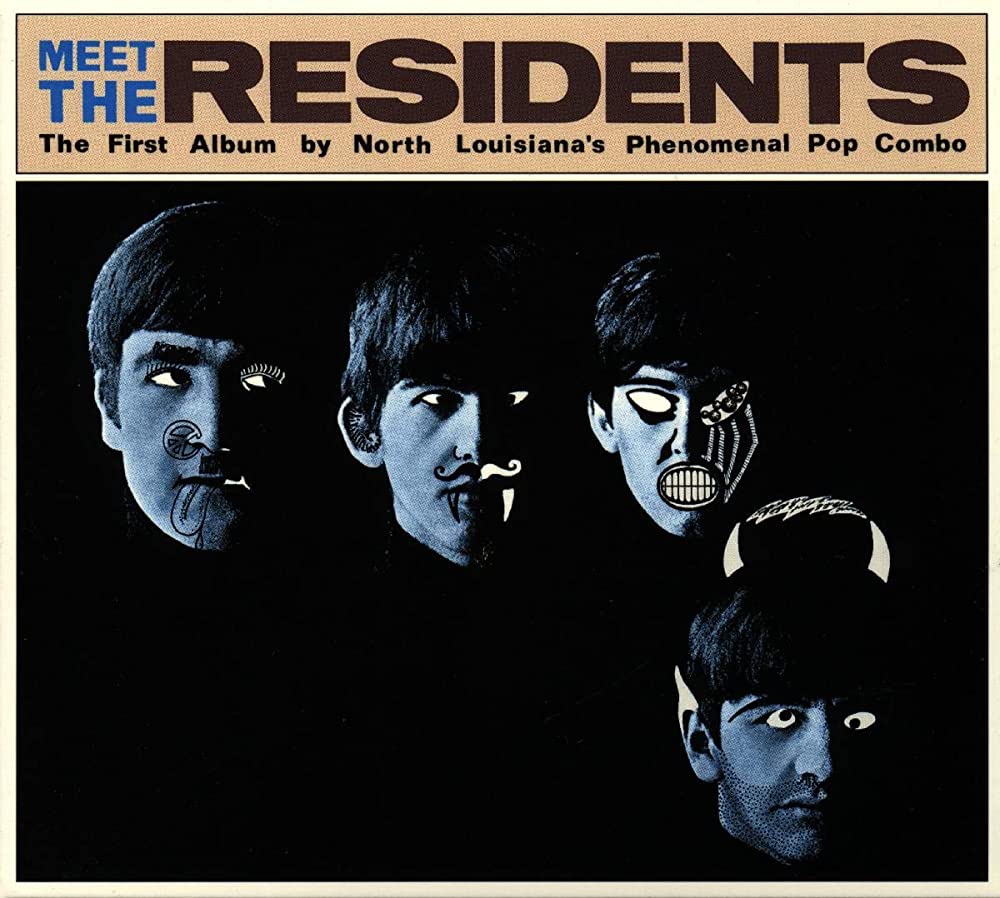

The biographical data is sketchy. They were friends in high school in Shreveport, Louisiana, in the early 1960s, and took off for California around 1966. They settled in San Mateo and began collecting musical instruments and recording equipment. In the early 1970s they started creating crazy, noisy, twisted music on reel-to-reel tapes, one of which they submitted to Warner Bros. – anonymously, sent with only a return address. When it was sent back it was addressed to “Residents.” And so it was The Residents who moved to San Francisco in 1972 and started their own label, Ralph Records, and formed the Cryptic Corporation. Santa Dog, a package of two 45s, was released the same year, and in April of 1974 they launched their first album, Meet The Residents – still maintaining their anonymity, something The Residents have never relinquished.

That’s the first unusual thing about Meet The Residents, even before you hear it – the fact that you never meet The Residents: The artists haven’t signed their names to their debut album. There are no faces either, only a nutty distortion of The Beatles. Which isn’t as evasive as you might think, because Meet The Residents builds on The Beatles’ innovations in the treatment of voices, instruments, lyrics, electronics, genre – Captain Beefheart’s verbal effusions and instrumental profusions are clearly a big influence too. And when you listen to the White Album or Trout Mask Replica, you just don’t know what you’re going to hear from one track to the next. With Meet The Residents, you can’t predict what you’ll be hearing from one moment to the next.

Forget about predictions – you can’t always be sure what it is you’re actually hearing. Some of this music is utterly inexplicable, as in how are they making that sound? You can’t even grasp the well-it’s-a-synthesizer straw, because this no-budget 1973 recording was plainly done by hand. It’s basically voices, piano, and winds; some guitar, bass, and drums; occasionally, brass and violin; lotsa percussion including household items and toys and debris and who knows what else. There are distortion effects through microphone and instrumental preparations, but it’s The Residents’ use of tape, the tracks they’ve razored and overdubbed and remixed and re-speeded, which makes their sound so uniquely bizarre. Plus a lyrical bent that treats language elliptically, folding words back in on themselves. And all these tracks are served up dripping with a playfully grotesque sense of humor.

For the 1997 CD reissue of Meet The Residents by East Side Digital, here’s how their music was positioned by the blurb on the back of the CD: “This is the first album released by The Residents. The recordings reflect the primitive nature of both The Residents[’] music and their recording technology in 1973. Not for the uninitiated, but the music is pure Residents. The Residents were decades away from digital samplers, midification, symphonic operas, and film scores.”

And so they were. But while I question the assertion that this music is as primitive as its equipment is, I have to say that what really strikes me in this blurb is how we’re told this music is “not for the uninitiated.” Meet The Residents was their debut album; when they released it forty years ago, the only people they could be making it for, the only people who could hear it, were the uninitiated!

And yet there’s a weird truth to this description, that their debut is not for the uninitiated. Edgar Allan Poe wrote a story in 1840 called “The Man of the Crowd,” and its opening line is, “It was well said of a certain German book that ‘er lasst sich nicht lesen’ – it does not permit itself to be read.” Well, in some ways this music does not permit itself to be heard. I’m reminded of Morton Feldman, he told me that his lengthy compositions were not geared psychologically for performance. We’re involved with similar creative contradictions here: Your introduction to an anonymous band opens with a nearly 8-minute track of … how many songs is this thing? If what you’re doing is unidentifiable and unnamable, then it might as well be unlistenable too. The Residents’ still-notorious cover of “Satisfaction” from 1976 was probably the zenith – or nadir – of that philosophy.

This CD of Meet The Residents discreetly subdivides the opening music into six chapters. Now, doing that only undermines the funhouse-ride quality of the original LP. But then, to commodify your art is to betray it – nobody can pay serious attention to American music without recognizing that process. How deep the betrayal is is a matter of what kind of commodity it becomes. This is why The Residents embraced anonymity, and why their music has systematically dissected the deeper implications of success in popular music.

So of course their first album starts by showing the holes in Nancy Sinatra’s “Boots.” And by demonstrating that, with the exception of their pianist, The Residents clearly were, at best, limited in orthodox musical chops – and their equipment wasn’t all that stellar either. They rub your nose in all that, right up front. Putting their worst foot forward is more than point of honor for them, it’s the point of their music. They don’t cover up deficiencies, they build songs around them. ‘Look at me, I can’t sing!’ ‘I don’t know how to play this instrument at all, lissen!’

And so anonymity is valuable, because it doesn’t matter who they are or how many of them there are or who’s joined them on a session – you could be doing this too. You don’t have to know how to play anything, you don’t need any special equipment. You just have to know how to listen – or at least know what it is you don’t want to listen to anymore.

James Agee wrote a very interesting essay about silent-film comedy back in 1949, and in it he described how, in the golden days of the Keystone Studios, Mack Sennett used to hire “a ‘wild man’ to sit in on his gag conferences, whose whole job was to think up ‘wildies.’ Usually he was an all but brainless, speechless man, scarcely able to communicate his idea; but he had a totally uninhibited imagination. He might say nothing for an hour; then he’d mutter, ‘You take…’ and all the relatively rational others would shut up and wait. ‘You take this cloud…’ he would get out, sketching various shapes in the air. Often he could get no further; but thanks to some kind of thought-transference, saner men would take this cloud and make something of it. The wild man seems in fact to have functioned as the group’s subconscious mind, the source of all creative energy. His ideas were so weird and amorphous that Sennett can no longer remember a one of them, or even how it turned out after rational processing. But a fair equivalent might be one of the best comic sequences in a Laurel and Hardy picture. It is simple enough – simple and real, in fact, as a nightmare. Laurel and Hardy are trying to move a piano across a narrow suspension bridge. The bridge is slung over a sickening chasm, between a couple of Alps. Midway they meet a gorilla.”

What The Residents did is put the wild man in charge. In the true spirit of surrealism, they deliberately set out to work with the uncensored and uncompromised unconscious, wherever it took them – how else could they dredge up anything, musical or otherwise, which was untainted by their conditioning?

The different personalities within the group work to cancel out whatever is derivative, egocentric, and pretentious from the others, destroying intentionality by multiplying intentionality, as John Cage would say. This is music that is all about escaping the boundaries of the conditioned mind, so they slap together segues that suggest the exquisite-corpse, they avoid technique, embrace chance and accident and malfunction, externalize the unconscious.

When you’re busy with all that, your name is only going to get in the way. Pulling the stick out of music’s ass means dispensing with the cult of the Artist, and The Residents are pre-punk vandals, spray-painting Duchamp mustaches all over the Louvre, laughing at the idea of celebrity by representing themselves on their debut album with a trashed image of The Beatles. Which again is not so much of an evasion. Hardy Fox, speaking for the Cryptic Corporation, told me about The Residents, “They don’t consider themselves to be new music. They think it’s a real hokey term. They like to think of themselves as pop musicians.” And that’s absolutely true. What else could they do but wade into the most shark-infested of waters, the musical arena where the betrayals and commodifications are the most violent and extreme?

Seeking to break the social and personal control exerted by the commodification of music for corporate profit, The Residents celebrated the bicentennial by releasing The Third Reich ‘N Roll, their savage and sometimes unrecognizable and always totally unauthorized and unpaid-for covers of 1960s pop tunes. Those covers also freed up The Residents to work more in short-song format, and turning more to synthesizers they released the twisted numbers of the albums Fingerprince and Duck Stab/Buster & Glen. Fingerprince also included an 18-minute composition, Six Things to a Cycle. Inspired by Harry Partch, it featured instrument building, unusual tunings, and rhythmic chanting – all of which fed into their most popular album, Eskimo, released in 1979. That classic record introduced a visual representation of the band that has stuck with them: four men in top hats and tails, whose heads are enormous eyeballs. It’s one of The Residents’ more overt surrealist references – René Magritte used the image in his 1963 painting The Difficult Crossing, the man has a large eyeball for a head.

In the 1980s, working with samplers changed the game significantly for The Residents and raised their music to a whole new level of expressivity and precision. One of their earliest efforts in this direction is still the most stunning: The Tunes of Two Cities, released in 1982, which depicts two societies – an exploited class of workers and a leisure class of owners – by representing them solely through examples of their music. The workers’ music is a dreamlike blend of the primitive and the technological. You get the sense that they live amidst the industrial detritus of the machines they work, fashioning their wind and percussion instruments from its scraps. All their music is ceremonial and religious, and in the cut I’m going to play for you, “Praise for the Curse,” they tackle another contradiction, the celebration of the yoke that has been forced upon them. Working with an Emulator, The Residents alternate wind sounds and machine music with electronic grindings, screechings, and drillings. All the searing industrialisms are stilled for a brief vocal solo – an extraordinary high shimmering voice, like a singing tuning fork – and then they bolt forward, more terrible than ever, but more dense and rich too, containing mechanical, vocal, and natural sounds, all teeming into an overwhelming scream.

To represent the owners, an even more original and striking and surreal effect is created. This music is all about pop and commerce, yet like the ceremonial and religious music of the workers, it too works in short forms with clearly defined sections that repeat and alternate. For all their differences, both musics are about the same thing, they serve the same purpose: the ritual exorcism of suffering. The owners are killing themselves on an over-rich, overfed diet, and their music inflates the American fantasy of power, self-indulgence, and leisure into a monstrous portrait of a society on the verge of collapse. It’s not unlike the novels of the Marquis de Sade – an author hailed by the surrealists as an essential progenitor – especially because The Residents are working here with an obsessive fixation, an unblinking stare in which fear and loathing are inseparable from worship and love. Which of course is exactly what we heard the workers doing in the previous cut. Only in this music The Residents emphasize – again, like Sade – the polished manners and rituals, the scrubbed and gleaming façades of their subject. So they turn to the white big bands of the 1930s and ‘40s, covering Bunny Berigan, Glenn Miller, Stan Kenton, and others – although none of these sources are ever mentioned or acknowledged on the album, just as no titles were given for any of the ‘60s pop covers of The Third Reich ‘N Roll.

In 1930 Aldous Huxley wrote, “Simplicity of form contrasts at the present time with richness of materials to work on. Modern simplicities are rich and sumptuous; we are Quakers whose severely cut clothes are made of damask and cloth of silver.” That’s also what’s happening in the owners’ music: extravagant, Emulator-engendered ensembles are put in the service of simple melodic phrases and familiar song forms. Combine that with the allusions to swing, and there’s only one way to describe the owners’ tunes: Art Deco music. The metallic textures, the glossy sheens, the contrasting surfaces, the lurid colors all point directly to Art Deco; equally Deco-like are the asymmetrical structures and jagged-yet-polite melodies in the music; also the high kitsch quotient, an unsettlingly sweet timbral tooth.

Art Deco is also the perfect apocalyptic idiom for this music. It had an abrupt, almost full-blown arrival and an equally sudden departure, and in its heyday it was a total design concept. They had Art Deco everything: houses, utensils, jewelry, clothing, furniture, statuary. That’s why now Art Deco can suggest the feeling of a vanished civilization – a world we can experience only in books or films or museums (a sensation intensified by the style’s reliance on Egyptian and Mayan forms). And then there is the resonance of Art Deco’s between-the-wars life span – revelers oblivious to the fact that, as Jim Morrison would say, their ballroom days are over, night is drawing near. Even the utopian idealism of Art Deco’s worship of technology now seems naïve, at best; at worst it implies a disappointment, even a disdain for humanity. Susan Sontag may not have been overstating the case when she observed that “the fascist style at its best is Art Deco, with its sharp lines and blunt massing of material, its petrified eroticism.” Which brings us back to the Marquis de Sade, via the Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, whose film Salò adapted Sade’s novel The 120 Days of Sodom to Mussolini’s collapsing republic, enacting the major atrocities in an Art Deco chateau.

You really can hear all of that in the cut entitled “Smack Your Lips (Clap Your Teeth),” which takes these qualities and opens them up ultimately into a toe-tapping threnody of cascading musical lines, with character after character entering the scrimmage, the harmonic foundation introspective and even mournful while the activity multiplying over it stays doggedly upbeat, refusing to notice that das Narrenschiff is headed for the falls.

This music of haves and have-nots meant a great deal to The Residents, evolving into a saga over several albums as well as a live show. They also went on to embrace the CD format in the late ‘80s with two of their finest works: God in Three Persons, a dark tale of sexual repression and the huckstering of religion, and The King & Eye, where they recast Elvis Presley as an epic commercialization of emotional need. Some of The King & Eye was also performed live, along with The Residents’ versions of cowboy and early African-American songs, as the Cube-E Show. In the 1990s they explored new interactive possibilities in the CD-ROM format with Freak Show, The Gingerbread Man, and Bad Day on the Midway. Several of The Residents’ later releases also spawned elaborate live shows, such as Wormwood, a series of songs taken from some of the more gruesome incidents in the Bible, and more recently Demons Dance Alone and The Bunny Boy.

I’d like to conclude this discussion of surrealism in 20th-century American music with some words about Robert Ashley. I remember speaking once with your teacher Anne LeBaron on the phone – this has to be some time in the 1990s – and we were discussing surrealist art and she told me of her enthusiasm for the work of Dorothea Tanning, and I immediately said, “Oh, she’s a very nice person.” Anne said to me, “You’ve met her?” And I answered, “Oh yes, several times, and it’s always been very pleasant.” “How do you know her?” Anne asked, and I explained that the niece of Dorothea Tanning is Mimi Johnson, the head of Performing Artservices and the Lovely Music record label, and the wife of Robert Ashley. That’s Mimi’s voice whispering in French in Bob’s Automatic Writing. And Dorothea lived in New York and would come to the performances of Bob’s music, so I saw her repeatedly, at concerts and parties and other circumstances, in the 1980s and ‘90s – she passed away in 2012 at the age of 101. She had a kind of natural elegance, and when I would see her she usually would sport a big hat or long gloves or some other kind of flourish, la vie de Bohème still lived with her, and it was really quite wonderful.

Dorothea’s husband of course was Max Ernst. They had been together since 1942, married in ’46 – at a double wedding with surrealist artist and filmmaker Man Ray and the dancer and model Juliet Browner, in Hollywood yet! And Dorothea and Max stayed together until his death in 1976, in Paris.

Bob once told me a very interesting story about his meeting Max Ernst, who had been one of his idols in his idolatrous youth. Bob was performing in Europe at the time and Mimi was with him, and they made a side trip to visit Aunt Dorothea and her husband Max in France. Bob was sick with a full-blown cold by the time they arrived and it was late at night, so they were hustled off to bed. And the next morning, Bob gets up and he’s running a fever, and he thinks to himself, ‘I’m sick with a fever and now I have to go downstairs and meet Max Ernst.’ He decides that the best way to do that is to get baked first, so he smokes up this reefer and then he gets himself together and goes downstairs with Mimi. And they’re with Max and Dorothea, starting to get acquainted, and Bob takes out a pack of cigarettes and asks Max, “May I smoke?” Max immediately replies to him, “You can smoke marijuana, if you want to.”

That story is especially interesting because Bob used that exchange with Max Ernst in his opera Atalanta (Acts of God), which was realized from 1982 through 1987. Each of the three Episodes of Atalanta is “dedicated to an artist who was very important to me when I was young”: Max Ernst, Bob’s uncle Willard Reynolds, for his nephew a “shaman storyteller,” and the jazz pianist Bud Powell. “[T]hree men whose artistic work influenced me deeply in my growth as a human being and as a composer.” The three also represent in Atalanta the visual, narrative, and musical aspects, respectively, of opera.

I want to share with you some special information about Automatic Writing. I recall speaking with Mimi one time and she mentioned to me how people were coming up to her and talking about this piece as a romantic or erotic work, hearing the interaction of her hushed French whisper and his distorted and transformed English as a kind of love story. Well, she just snorted at that notion, dismissed it out of hand. “That music is about fear,” she said to me.

And so it is. The fourth character that comes about in Automatic Writing on the Polymoog did indeed have its own quality of involuntariness to it, just as the other three did. Bob was then living on his own in Oakland, and the neighbors’ speakers would pump the bass lines of their disco music into his apartment. He’s re-creating the force-feeding our ears are subjected to, with all its unpleasant connotations of other peoples’ disregard for your existence.

As for the other three characters being involuntary, this is how Ashley explained it to Tracy Caras and myself when we interviewed him in 1980 for our book Soundpieces: “The English words were the closest that I could come, after working in it for a long time, to involuntary speech. And so the English has allowed the characteristics of involuntary speech. […] I was working with involuntary speech as a sound for a few years and finally did a recording – a very high-quality recording – of my own involuntary speech. But I wanted to remove the quality of ‘intimacy’ from that recording. I wanted it to be heard as ‘involuntary,’ rather than just ‘intimate.’ […] After about a year, I had an idea about how to do that with a synthesizer and a digital switching device that Paul DeMarinis had built for me. After working that out, then, I had a tape with two characters on it: the involuntary speech and the synthesizer character – which was, amazingly, involuntary in a complementary fashion, technically: I designed a circuit to do one thing, and when I set it up, it did exactly the opposite. I mean a total antithesis of what I understood the circuit would do. (It’s still very mysterious to me; to this day I don’t understand why the circuit worked that way, and I know something about what I’m doing.) So when I heard that antithesis, when I heard that quality, it was really a shock; it was like the entry of a second character into a play. […] I asked Monsa Norberg, who speaks eloquent French, simply to make a translation of the involuntary speech. [… S]he just translated phrases as best as she could, even though, out of context, they didn’t take precise translations. I didn’t have time to do the recording of the translation until I got to France. I did the recording in a very small office, sort of the day before the premiere of the piece. And the technical situation was such that when Mimi Johnson was doing the reading of the text, she couldn’t hear the English version; I was wearing headphones and I would point to a certain phrase when it came up, and Mimi would read it. Because her inflection was unpremeditated, just because of that situation, it was like a different version of the same quality that I had been listening for in the original tape. It was totally accidental, just a technical thing, but it was a wonderful thing to happen. Then I started thinking about the actual subject that I discovered in the text of the involuntary speech: The text was all about ‘fourness.’ It’s all about the quality of ‘fourness.’ So I got fascinated with the idea that there were meant to be four characters in the piece. […] I started looking for the fourth character, because that had been predicted by the text. […] I finally did it on the Polymoog. I worked at that character on the Polymoog for about a month. […] When that character appeared, it appeared with exactly the same unpremeditated quality that the other three had, so I knew then the piece was finished.” Let me just add here that what Ashley meant by “fourness” characterizing the involuntary speech is that everything he involuntarily said came out in either groups of four words or clusters of four syllables.

This theme of the involuntary is something to consider, because it’s been running throughout this discussion, from the piano that wouldn’t stop playing Mendelssohn to Nancarrow’s pianos playing by themselves to Buñuel losing his hearing to the presence of inexplicable sounds on tape that were generated by you playing your instrument to the unstable and transforming voices of computer speech. The Residents, although they might create the impression of being anarchic and unbridled, almost always work with some kind of deconditioning discipline, imposing constraints of a formal or conceptual principle: the comparative study of The Tunes of Two Cities, covering ‘60s top 40 with The Third Reich ‘N Roll, the fake anthropology of Eskimo, the Commercial Album’s yoke of brevity, with each song lasting exactly sixty seconds, the toy instruments and nursery rhymes of Goosebumps, singing in an invented language in The Big Bubble, the covers of their American Composer series. But Ashley put the theme right up front in Automatic Writing, with involuntarism defining all four of the piece’s characters.

In surrealism, from Buñuel to Ashley, you lean into the involuntary situation rather than resist it, just as, in a dream, you usually don’t question what is absurd or humiliating or impossible – or all of the above – but engage with it and cooperate with it. What you do voluntarily are the things the conscious mind selects to engage with. Choice, purpose, dialectic, as Pierre Boulez would say. And that means the conditioned mind is at work, so what you’re doing is also, to a significant degree, involuntary. Like I said, A is B. Pavlov’s dogs didn’t drool by choice when the bell rang. But that of course was an imposed response. That which is natural and involuntary defines us biologically, the internal processes going on in our bodies without our supervision; when they want to make sure you’re OK, they test your reflexes, tapping your knee or your Achilles tendon to make your leg jump. The involuntary is a sign of life.

(This lecture was first given at the California Institute of the Arts in April of 2016.)

SOURCES

“There was no other way”

Harold C. Schonberg, The Lives of the Great Composers, third edition. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997, p. 164.

“I usually end up”

“Some of the rhythms developed”

Henry Cowell, New Musical Resources. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 64–65.

“From the time I started composing”

Nicole V. Gagné and Tracy Caras, Soundpieces: Interviews with American Composers. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1982, p. 287.

“Men too secrete the inhuman”

Albert Camus, “The Myth of Sisyphus” in The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays. Justin O’Brien, trans. New York: Vintage International, 1991, pp. 14–15.

“dead”

Pierre Boulez, “Where Are We Now?,” in Orientations: Collected Writings. Edited by Jean-Jacques Nattiez. Martin Cooper, trans. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1986, p. 456.

“footnote”

Boulez, “Taste: ‘The spectacles worn by reason’?,” in Orientations, p. 61.

“a lot of fuss about nothing,”

Boulez, “Taste,” Orientations, p. 60.

“Everything tends to make us believe”

André Breton, “Second Manifesto of Surrealism” in Selections. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane, trans. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003 pp. 152–153.

“the chance encounter on a dissecting table”

Comte de Lautréamont, The Songs of Maldoror. R.J. Dent, trans. London: Solar Books, 2011, p. 210.

“The surrealist practice of collage”

Pierre Boulez, “Entries for a Musical Encyclopedia,” in Stocktakings: from an Apprenticeship. Collected and presented by Paule Thévenin. Stephen Walsh, trans. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991, p. 226.

“You’d be dancing”

Nicole V. Gagné, Soundpieces 2: Interviews with American Composers. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1993, p. 343.

“My vision of it”

“I had imagined the ghost pieces”

“the blend is what I expect”

Gagné, Soundpieces 2, p. 347.

“as late as possible”

Gagné, Soundpieces 2, pp. 347–348.

“it’s this world we’re looking into”

Gagné, Soundpieces 2, p. 348.

“a romantic, poetic response”

https://www.thehorsehospital.com/archives/past/live-past/justin-snyder

“The Speech Songs“

Gagné and Caras, Soundpieces, p. 148.

“Laughter at new music concerts”

Charles Dodge, CRI LP SD 348 liner notes.

“That to me was finally the essence”

Gagné, Soundpieces 2, p. 348.

“This is the first album released by The Residents”

ESD 81222 liner notes.

“It was well said of a certain German book”

Edgar Allan Poe, “The Man of the Crowd” in Poetry and Tales. New York: Library of America, 2005, p. 388.

“a ‘wild man’ to sit in”

James Agee, “Comedy’s Greatest Era” in Film Writing and Selected Journalism. New York: Library of America, 2005, p. 16.

“They don’t consider themselves to be new music”

Nicole V. Gagné, Sonic Transports: New Frontiers in Our Music. New York: de Falco books, 1990, p. 7.

“Simplicity of form contrasts at the present time”

Dan Klein, All Colour Book of Art Deco. London: Octopus, 1974, p. 11.

“the fascist style at its best”

Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism” in Under the Sign of Saturn. New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 1980, p. 94.

“dedicated to an artist who was very important to me”

Robert Ashley, “Telling Stories in an Unusual Way” in Outside of Time: Ideas About Music. Köln: MusikTexte, 2009, p. 278.

“shaman storyteller”

Robert Ashley, Lovely Music CD 3301-2 liner notes.

“[T]hree men whose artistic work influenced me deeply”

Ashley, “Empire (1982–1991)” in Outside of Time, p. 602.

“The English words were the closest that I could come”

Gagné and Caras, Soundpieces, pp. 24–25.

Link to:

Music: Lectures: Contents

For more on these composers, see:

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music: SFCR Radio Show #26, Surrealism in 20th-Century American Music

More Cool Sites To Visit! – Music

For more on Robert Ashley, see:

Music Book: SONIC TRANSPORTS: “Blue” Gene Tyranny Essay, part 6

Music Book: Soundpieces: Interviews with American Composers

Music Essay: Anne LeBaron, Hyperopera, and Crescent City: Some Historical Perspectives

Music Essay: You Can Always Go Downtown

Music: SFCR Radio Show #5, Postmodernism, part 2: Minimalism

Music: SFCR Radio Show #12, A Tribute to Robert Ashley

Music: SFCR Radio Show #35, Electro-Acoustic Music, part 3: Musicians and Synthesized Sound

For more on Pierre Boulez, see:

Music: SFCR Radio Show #18, Gunther Schuller and Pierre Boulez at 90

For more on Pierre Boulez and Conlon Nancarrow, see:

Music Lecture: “Intense Purity of Feeling”: Béla Bartók and American Music

For more on Luis Buñuel and Conlon Nancarrow, see:

Film Dreams: Luis Buñuel

For more on Conlon Nancarrow, see:

Music Book: Soundpieces: Interviews with American Composers

Music Essay: Conlon Nancarrow

Music Lecture: The Secret of 20th-Century American Music

For more on The Residents, see:

Film Review: The Eyes Scream

Film Review: Triple Trouble

Music Book: Sonic Transports: New Frontiers in Our Music

Music: KALW Radio Show #7, In Tribute

Music: SFCR Radio Show #7, Postmodernism, part 4: Three Contemporary Masters

Music: SFCR Radio Show #27, 20th-Century Music on the March

For more on Morton Subotnick, see:

Music: SFCR Radio Show #33, Electro-Acoustic Music, part 2: Musicians and Tape