The Third Reich ‘N Roll

Best Defense

In 1975 The Residents launched a major offensive into Top 40 of the 1960s. They came back not with prisoners but souvenirs – in The Third Reich ‘N Roll, pop standards are reduced to a uniquely Residential pile of mummified ears and severed fingers. I really can’t think of a precedent for this album. The closest contender, I suppose, is Spike Jones. His music may well have been in the back of The Residents’ collective mind, especially for its flourishes of black comedy: the gunshots and shrieks of “You Always Hurt the One You Love” or the pyromaniacal “My Old Flame” (my favorite Spike opus, particularly for Paul Frees, whose Peter Lorre vocals keep deteriorating into M-like confessional hysteria). Certainly Jones’ fondness for musically punning on a song’s lyrics turn up in Reich ‘N Roll: airplane noises segue into “The Letter”‘s demand to “Gimme a ticket for an aeroplane”; hungover singers and a barrage of gunfire provide “A Double Shot of My Baby’s Love.”[1]

I suspect The Residents would be particularly charmed by Spike’s enthusiastic impalings of popular love songs. But this is also where the basic difference between Jones and The Residents is most apparent. Spike would only prune the branches of romance, whereas the Residential approach is always to go for the roots. Their bushwhacking has a vehemence that smacks of misogyny in Duck Stab / Buster & Glen and Commercial Album; Reich ‘N Roll, to its credit, never gets that vicious. Or maybe it’s just that this sourness is more comfortably comic: Their hilarious cover of ‘It’s My Party” has horror-movie shock chords and oversizingly echoed female vocals, transforming the lament of the 5-foot girl into the attack of the 50-foot woman. (I sure wouldn’t want to be her Johnny when she finds him.)

“Party” is only one of the many unbelievable pissers on Reich ‘N Roll – Johnny’s rambling modifications, which segue that song into “Light My Fire,” are almost as funny as “Party” itself. The gelatinous vocal line of “Yummy Yummy Yummy I’ve Got Love in My Tummy,” writhing and shuddering with demented delight in and around the melody, is one of the wildest, most inspired moments in all The Residents’ music. (Just the fact that that song is on the album bends me all out of shape.) And for plain zaniness, their boisterous “Land of a Thousand Dances” blows away everything else on the record – except maybe for the burbling waters and electronic squawks that end Side One.

But for all its yocks, Reich ‘N Roll supports Jay Clem’s insistence that “The Residents hate comedy or overtly serious music. With comedy, you’re only interested in a ‘laugh,’ whereas when you are working with a serious statement, you can get involved with too much negativity and pretentiousness.”[2] Spike Jones made comedy music; he was always only kidding, and always made sure you knew he was only kidding. No matter what bizarro areas he’d wander into, Jones would typically end by tacking on a reassuring chord or two: You’re back, it’s OK – c’mon, applaud. (That, along with the cookie-cutter uniformity of his songs’ durations, can make it hard to listen to an albumful of his stuff.) His parodies didn’t have much to fall back on other than laffs, and today an unhealthy percentage of the gags come off sounding laborious and trivial. Those that live by the Birdaphone, die by the Birdaphone.

No matter how whacked out Reich ‘N Roll gets – and it sure does get awfully whacked out – its cuts are covers, not parodies. Jones was a parodist, and so was dependent on his audience’s familiarity with the original songs – you have to get the joax, foax.[3] Reich ‘N Roll never gives the titles of its tunes; part of The Residents’ virtuosity is in reinventing an old fave so radically that it becomes unrecognizable.[4] The ‘joke,’ the contrast between the original and their cover, is like the prize in a Cracker Jack box: a little something extra, tucked away for anyone who cares to dig for it. Surrealism is frequently funny, but its point isn’t simply the gag. The event has to be a compelling piece of weirdness, independent of any joke.

And The Third Reich ‘N Roll is filled with music that is, by anybody’s definition, compellingly weird: the backwards sounds of “The Letter”; the avalanche of dissonant keyboards and the warpath finale of “Yummy Yummy Yummy”; Side One’s climactic collage of songs and noises and auto horns. There are plenty of other tape tricks on the album, but every now and then something is batted out which is all the weirder for being done live, such as the vocal growls and howls distilled from an obsessive refrain of “My Baby Does the Hanky Panky,” or the drums, honkers, and rubber woozers of the insane intro to “Land of a Thousand Dances.”

I Love You, I Kill You

To an extent, The Residents selected tunes for Reich ‘N Roll the same way The Beatles picked faces for the cover of Sgt. Pepper: campy, pomposity-deflating jokes are arranged cheek-to-jowl with genuine homages. Reich ‘N Roll chews over and spits out bubble gum like “It’s My Party” and “Yummy Yummy Yummy.” But it also acknowledges The Residents’ admiration for the rhythmic imagination of “Good Lovin’”; the sound effects in “The Letter”; the instrumental chops of “Wipe Out”; the psychedelia of “Sunshine of Your Love.”[5] Admiration, however, can be a serious handicap if you want to do something original in short-song format. You can be demoralized by awe and lose your urge to create. Worse, you can wind up continuously aping this stuff, whether it’s good or bad, just because you’ve been bombarded with it since birth. The Residents shrewdly decided to fight fire with fire and get out from under pop’s thumb by singing it to death. Reich ‘N Roll’s homicidal homages were a kind of Enema Variations, purging them of their worst songwriting blocks: Between 1976 and 1978, they would record over two dozen original songs, most notably those of Fingerprince and Duck Stab / Buster & Glen.[6]

Locking themselves into the cover factory of Reich ‘N Roll also unblocked a surprising expressive range in their music. The Residents had never (still haven’t, in fact) done anything more delightful or… well, charming than their disembodied, blissed out rendition of “Good Lovin’” – it has to be that song’s definitive cover, if not its definitive version. Equally impressive is the pathos and bitter resignation of the unsettling slow waltz that they squeeze out of “The Ballad of the Green Berets.”

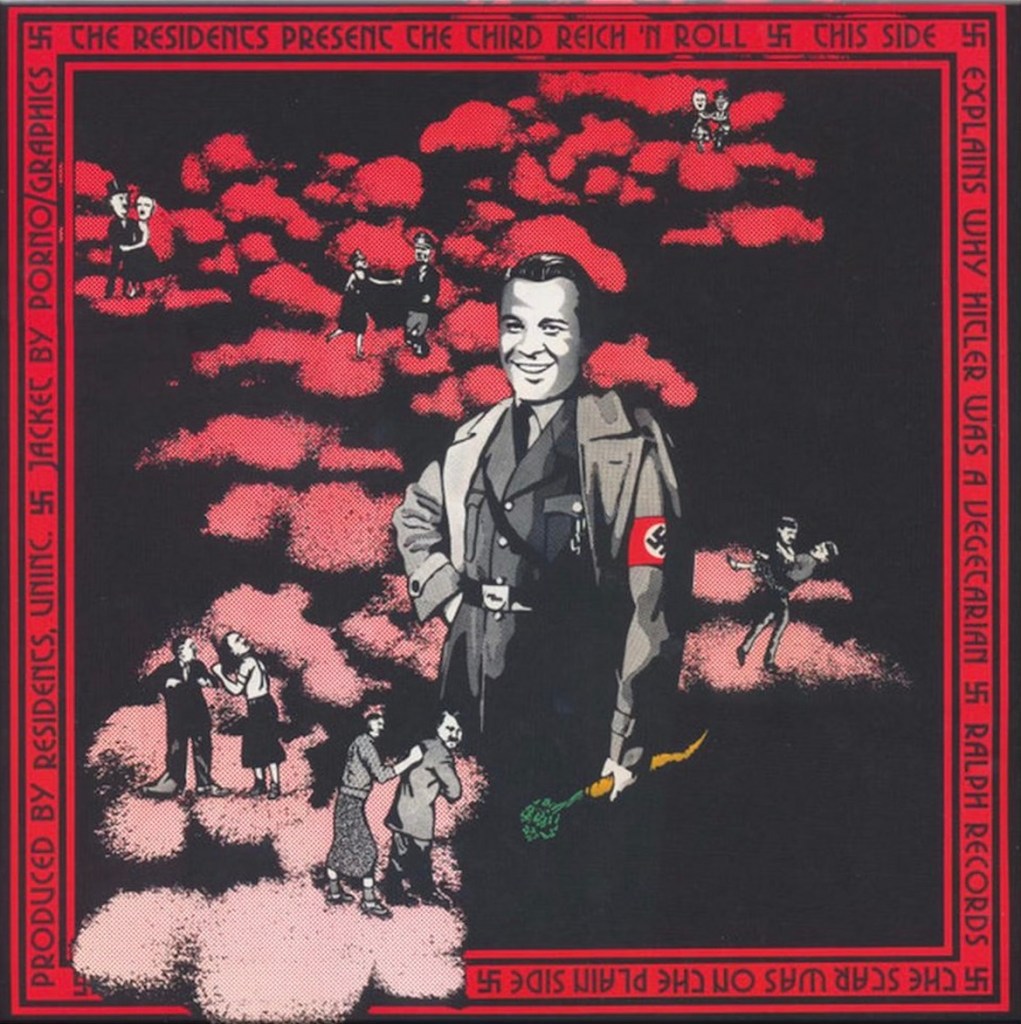

Sgt. Barry Sadler reports for duty on Reich ‘N Roll because he too infiltrated the top ten back in the ‘60s. Rock music is only secondarily an aesthetic commodity; first and foremost, it is a global, multi-million-dollar industry with inflexible ideas concerning what is and is not an admirable, successful human being. As such, it’s the All American smiler with the knife, encouraging people not just to sit back and relax, not just to Buy, but to believe. That’s why the cover of The Third Reich ‘N Roll is replete with swastikas and dancing Hitlers, and features a portrait of Dick Clark in Nazi drag. And why its sides are entitled “Swastikas on Parade” and “Hitler Was a Vegetarian.” And why Side One goosesteps off with “Let’s Do the Twist,” an imperative whose implicit arm-twisting is made explicit by the fake-German vocals, and why the album is punctuated by the sounds of machine guns and a dive bomber.

The Residents wanted to do more than get pop out of their system. They wanted to get it off their backs – off ours too. The liner notes of Reich ‘N Roll observe, “Already people are speculating whether the residents are hinting that rock ‘n roll has brainwashed the youth of the world. When confronted with this possibility, they replied, ‘Well it may be true or it may not, but we just wanted to kick out the jams and get it on.’ […] We, as the parent company, support The Residents and their tribute to the thousands of little power-mad minds of the music industry who have helped make us what we are today, with an open eye on what we can make them tomorrow.”

Four Men and a Prayer

All of Reich ‘N Roll’s themes come together in the way the residents treat – surprise! – The Beatles. The last chunk of Side Two begins like an old radio thriller, with an ominous organ flourish that condenses into “Inna Gadda Da Vida.” This cover gets some temporary support from a vocalist who sounds like Gabby Hayes in a straitjacket, but as things become increasingly dense and noisy, the organ slips into “Sunshine of Your Love,” only to have a low, undulating theme skim off the Cream and pull the organ into a dissonant version of “Hey Jude”‘s finale, complete with wordless Residential voices.

Covering The Beatles was inevitable for Reich ‘N Roll. No one more luridly represented the pop star as cultural dictator, as worshipped myth, than the Fab Four did; no one’s music was as stimulating or variegated, and so no one had to be more ruthlessly exorcised if The Residents were to tap something original inside themselves. If there’s any surprise, it’s that “Hey Jude” got the nod over so many other possible candidates. A specific homage seems implied, probably due to the song’s radical treatment of scale. The Residents’ covers of “Light My Fire” (43″) and “Inna Gadda Da Vida” (70″) are brutally terse, suggesting the snipping those songs underwent before they could ride the radio waves – the only surfboard into the sunset of American pop in those pre-video days. But The Beatles blitzkrieged onto AM radio a song that listed over seven minutes. Picking “Hey Jude” also acknowledges The Residents’ debt to the McCartney wing of the Beatle estate, especially Paul’s free and uncensored approach toward instrumentation, segueing, song length, role-playing vocals, and above all, genre-plundering.

But ending in the spirit of admiration – no matter how dissonantly – doesn’t do much when it comes to deconditioning, so The Residents include a fancy guitar in “Hey Jude.” It starts with a straight quotation of The Beatles’ melody but is gripped by noise seizures that eventually transform it into a straight quotation from “Sympathy for the Devil.” The album ends with The Rolling Stones’ melody stingingly played, accompanied by hoo-hooing voices, while The Beatles’ tune goes on and on and on and on.

The Residents are trading on the idea that, in The Stones, The Beatles had “unwittingly inspired their own sinister doppelganger, an anti-Beatles.”[7] A great way to free yourself from an obsession is to yoke the idea to its opposite. They’re also mimicking the tin-eared commentators who have always equated The Beatles and The Stones: two long-haired British rock groups, right?

The music of the two bands is very different, yet work of The Beatles’ imagination and originality could be seen by its admirers as interchangeable with stuff by The Stones (even when they weren’t imitating The Beatles). The Residents may also be scratching their eyeball heads over that one. What further proof do you need that it doesn’t matter how obscure or well known you are? However hard you work at what you do, people hear what they want to hear, not whatever it is you’re playing. Which is actually a relief: There’s no such thing as a musician being heard, so let’s not act like all this stuff is such a big deal, and just do what we want to do, and go on kicking out the jams, OK? And you know, The Stones could rock solid when they worked at it, and chops is chops, ja? A little rachmones for these devils, please. And while we’re at it, some sympathy for pop – one of the liveliest roads we’ve ever paved into consumerism and conformity.

FOOTNOTES

1. There’s also the cardiac beat of Subterranean Modern’s “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” And one reason why The Residents’ cover of “Satisfaction” is indeed the most determinedly repellent piece of music ever recorded is so we can appreciate just how hellish it is when you literally, really, truly can’t get no satisfaction.

2. Patrick Roques, “Meet The Residents” in Vacation, Spring 1981, p. 4.

3. Which is why the Walter Mitty puerilities of a “Weird Al” Yankovic represent the problem, not the solution.

4. I can’t identify all the tunes. Being that transformative also helps The Residents elude the copyright bloodhounds, but that’s probably a fringe benefit – apparently, they’ve never hesitated to do something because of copyright considerations.

5. Jay Clem also says to Patrick Roques in Vacation, “They loved psychedelic music. If psychedelic music hadn’t gotten so washed out in the ‘70s, The Residents may have never gotten into music.”

6. That averages out to more than one song a month, which is pretty good – especially when you consider they also covered “Satisfaction” and “Flying” during this time and recorded the 18-minute Six Things to a Cycle.

7. Steven Simels, Gender Chameleons. New York: Timbre Books, 1985, p. 32.

Links to:

SONIC TRANSPORTS: The Residents Essay, part 3

SONIC TRANSPORTS: The Residents Contents

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Contents

For more on The Residents, see:

Film Review: The Eyes Scream

Film Review: Triple Trouble

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music Lecture: My Experiences of Surrealism in 20th-Century American Music

Music: SFCR Radio Show #7, Postmodernism, part 4: Three Contemporary Masters

Music: SFCR Radio Show #26, Surrealism in 20th-Century American Music

Music: SFCR Radio Show #27, 20th-Century Music on the March