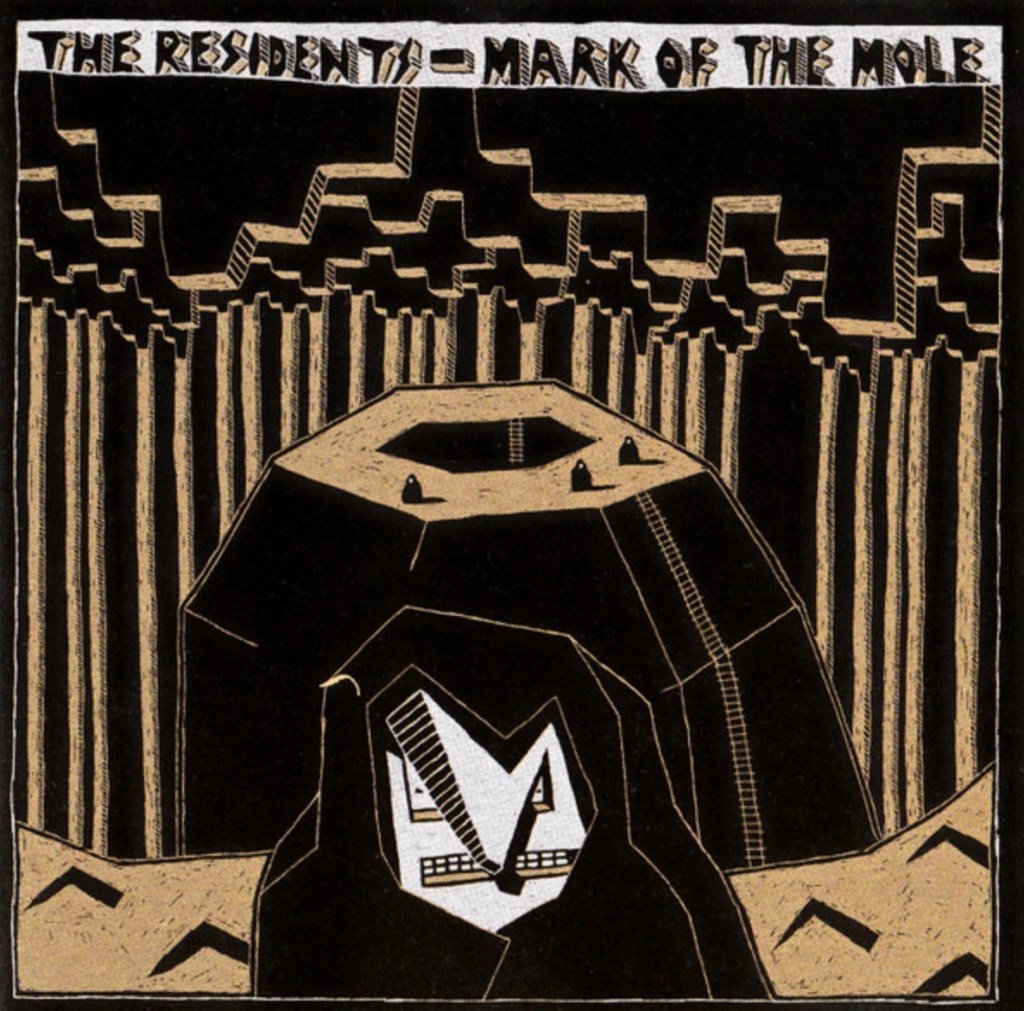

Mark of the Mole

Underworld U.S.A.

Less than a year into the freshly hatch’d Reagan administration, The Residents released Mark of the Mole. They’d “decided that a disaster was in order,” says an anonymous Cryptic Corporation exec. “They felt compelled to create something cold and grim, without a single smile.”[1] That may be putting it a little too strongly, but a barrel of laughs, Mark of the Mole is not. The album is the first installment of a projected Mole Trilogy. The Tunes of Two Cities, released the following year, is part two (it has some laughs too!). With these two albums, The Residents have created their most urgent and impassioned music. This stuff meant enough for them to take it before the public in 1982–83 as their potent music-theatre piece, The Mole Show.[2]

Mark of the Mole describes two classes, owners and workers. A natural cataclysm ejects the workers from the land they’ve tended for generations, and forces them to migrate to the owners’ territory, where they’re met with fear, hatred, exploitation, and ultimately violence. Essentially, it’s the story of the dispossession of the Dust Bowl farmers. But Mark of the Mole‘s surrealistic saga encompasses several American traumas. The workers are Moles that labor underground, keeping everything humming for the Chubs, their masters who live on the surface. The Moles are a different race used as slave labor, and a sudden freedom brings them into a bloody confrontation with their former owners. Sound familiar? There are other Resinances too, most notably the immigrant experience and the Trail of Tears. (And that’s just sticking to the states; Mark of the Mole also gives off sparks of Africa and the Middle East.)

The album opens with high fluctuating electronics, an insistent bass, metallic percussion, and echoey timpani, all played against distant watery sounds. You’re going down into the world of the Moles, a gargantuan network of tunnels, factories, and generators. As you descend, a female voice drifts past: “People must be left alone unless they have a happy home.” Hmm… Well, yeah. But shouldn’t we be helping people who don’t have happy homes?

While you’re chewing on that, you’re also half-listening to the bland warnings of a remote and fuzzy newscaster. And like most of the real media squawks we absorb, the news is not good. A large storm is forming in the pit area, from “an unusual influx of unseasonably cool winds sweeping down into the infamous pit heat. Meanwhile here on the West Coast, the weather has continued much as it has for the last week.”

That geographical in-joke is only one autobiographical allusion in Mark of the Mole. The Residents also depict the most hostile Chub factions as card-carrying rednecks. This cliché is apparently very real for North Louisiana’s phenomenal pop combo – they moved to S.F. for a reason, you know[3]. But taking the boys out of the bayou doesn’t take the bayou out of the boys. Like Thomas Pynchon, another faceless apocalypse-monger who moved to the nice weather of the West Coast, The Residents apparently feel a certain dismay over belonging to the white American bourgeoisie. It’s those other peoples who have values and souls, who are actually capable of loving their environments and their bodies and their deities. Us palefaces know they’re better than we are, and it drives us crazy. Profit, shmofit – we decimate their cultures because we can’t live with their reminder of how empty we are. Making a buck off them just hides our motives from ourselves… a nightlight against the monsters of self-recognition.

“The Ultimate Disaster” sketches in the world of the Moles, depicting the natural catastrophe that ends their old existence forever. It features four Mole songs, three of which are dominated by a nameless shaman who serves as the spiritual heart of the Moles’ society. He’s characterized with a brilliant deep voice, breathy and metallic, as though this Resident was singing through a length of pipe. “Won’t You Keep Us Working?” is his dynamic howling appeal to the god who made “all of the motion without light.” But a storm shuts down the underground machinery in a wild gale of electronic glissandi, storm sounds, and other whatchamacallits.

When the machines rev up again, an old, trembling, Uncle Tom Mole sings a slow song of praise, heavy with Residential irony: “Harmony cannot be denied; once again we are satisfied; / Calm and quiet have been restored; so it is as it was before.” But the machines apocalyptically collapse in a mad dance of screeching, short-circuiting electronics. The residents dig into the visceral possibilities of musicalizing an industrial catastrophe, and the music roars into an upward glissando that climaxes with a high blinding hiss, as though everything has melted down. Loud, this passage has a real wallop – it may not be “Arctic Hysteria,” but it ain’t bad either.

One From The Heart

A new song follows the stilling of the heavy machinery, and it’s the first major surprise of this surprise-filled record. After years of role-playing, cynicism, and derision, The Residents actually feel something and want to communicate it. What’s even wilder is that they succeed. Backed by a slow mechanical pulse, a chorus of male and female voices asks over and over, “Why are we crying,” turning the word “crying” into the act of crying, taking a gliss down a minor third. The life cycle of work-eat-sleep has abruptly stopped, and for perhaps the first time in their lives the Moles are recognizing and experiencing their own emotions. The shaman leads the chorus, his singing bizarrely mirrored by a low croaking voice. A for-real spiritual leader, he guides his people not simply to voice their sorrow but to learn from it – why are we crying? And as the Moles flee their flooded homes, he directs them to a new existence, urging them to head out to the sea.

Side One concludes brilliantly with “Migration.” The first of this trio of songs is “March to the Sea,” where the shaman is still holding everyone together: “Smiling from the gentle touches of the evening breeze / No one is unhappy now and no one is fatigued / We’re marching to the sea, marching to the sea.” A high metallic line counterpoints his vocals; eventually a hornlike melody joins in. The total effect is lovely – martial, courageous, and just a little absurd and cartoony. It’s also extremely visual: a perfect far shot of the Mole procession heading toward the sea.

But we’re not the only ones “watching shadows moving across the sand.” The second song, “The Observer,” introduces our Chub alter ego, “a tired old man in a tired old land”; an ominous redneck, complete with shitkicking accent, plucked electric guitar, and clipclopping wooden percussion. There’s also a backdrop of thunder and sirens, seeing as how we’re getting closer to Big Trouble. He darkly concludes that no matter how pure something is, “it cannot stand in a distant land.”

Nothing The Residents ever did has the passion and intensity of “Hole-Workers New Hymn,” the last of the “Migration” songs. Soon after I began following their music, I became convinced that they could achieve anything they could imagine. But I still didn’t expect a triumph like this. The hymn opens with high, birdlike, electronic burblings, beautifully evoking the courage and awe of the Moles’ entry into a new world. A bass ostinato fades up, launching the melody, and high-register, organlike phrases gradually fill in the hymn. The Residents’ sense of timing has never been sharper than in their staggering of these events, particularly the slow, slow welling up into clarity of the voices that shadow the bass line, singing “Let my children live in a holy land.” When the hymn reaches its zenith, the shaman soars in with a terrible power and urgency:

We have left our lives, we have left our land,

We have left behind all we understand,

Now we must cry out, yes we must demand –

Let my children live in a land that’s low,

Where the holes are deeper then light go;

Let them have not pride but instead of soul

That can see the shame of the hands that glow.

The song zeroes in on one facet of the immigrant experience, the people who came – and still come – to America not to get rich, but to ensure that their children will never suffer as they have; the people who believe that it’s too late for themselves, who have been stripped of everything except a dream of the next generation’s freedom. “Hole-Workers New Hymn” distills this extremity of sacrifice, and it can break your heart.

The hymn is so strong that you can miss the Residential pun: The Moles want their children to live in a hole-y land. Their idea of paradise is bound up with life underground, in a hole; the life that physically separates them, and so frees them, from the Chubs. The hymn ends with a malediction against the Chubs, and the thunder and sirens that close Side One warn that a real shitstorm is brewing. When The Observer sang of what he saw, he used the melody of the hymn – the people already living there want their children to live in a holy land. Why isn’t hallowed ground big enough for everybody?

Doctor Cyclops

Side Two’s “Idea” introduces the Chubs’ high priest: an industrial scientist. Unlike the Moles’ shaman, this thin fuzzy voice (intelligible only a few strain) seems barely cognizant of his own feelings and ideas, let alone anyone else’s:

Today I have declared myself to be a subject of the will of the people. Too long have my studies and research been for my own pleasures and distractions. […] My first project will be the freeing of our underground workers. […] Creatures! Seek your dignity!

The Moles’ shaman always commands full attention; as soon as the scientist begins talking, he is razzed by a flatulent background of his own percolating chemicals and machinery. A non-industrial wizard such as Eskimo’s “Angry Angakok” could save face by conjuring up some heavy action; the scientist is just a necki – ironically, an even bigger necki when he succeeds than when he fails.

His initial construction is a thinly textured waltz, brilliantly combined with his whistled fragments of the background melody of “Idea” – there’s more hubris in that whistle than in any lyrics The Residents could have given him. Work on the machine includes “Ugly Rumors,” apparently a chorus of Chub hardhats. If you listen hard to this mass of growling gripers, you can catch a Resident doing a very funny, 110-proof Strother Martin, reciting the full catalog of redneck fears: The Moles are lazy, they’ll want us to support them, they’ll screw our daughters…

The scientist starts to get creepy when he rants that “All will hail the new machine!” And when his device roars into life, his rhetoric loses all restraint: “The golden age quivers on the brink of creation. Live, my machine! Live, my savior! You have my breath […] You have my dream, my dream.” What dream is this? Well, “Success” eerily depicts the irresistible growth and power of this machine, roaring past us like a locomotive. Or a tank. (The ambiguity of the sound blunts its impact; in The Mole Show, you were shown that the scientist has built an instrument of warfare.)

Part of Mark of the Mole‘s tragedy is that good intentions pave the road to you-know-where because all our materials are fundamentally anti-human – we’ve lost the knack for life. The religious edge to the scientist’s celebration of his machine is nothing but the worst kind of idol worship. The residents are evoking the theorem of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film Teorema: Nothing comes from nothing; a bourgeois is always a bourgeois, and therefore always wrong, even if he turns over his factory to the workers. But at least Pasolini was still arguing that the sub-proletariat had a basic humanity and capacity for life. Mark of the Mole betrays a deeper despair, when the besieged Moles respond not just in violent self-defense, but with utter malevolence and hatred.

Hell’s Highway

In “Final Confrontation,” the last section of Mark of the Mole, the Moles turn on the Chubs, singing, “We don’t want your brow, we don’t want your eye, / All we really want is for you to puke and die!” This song segues into the shaman’s “Don’t Tread on Me,” where two plucked electric guitars move in and out of sync – a recollection of the accompaniment for “The Observer,” again equating Moles and Chubs. The Residents include a stunning effect here, like mechanical frogs: gargled croakings that suggest some intermediate stage between animal and machine. The Chubs’ chickens have come home to roost, but at what cost to the souls of the Moles? Don’t ask the shaman, he’s too busy singing

Hatred has dignity, hatred is clear,

Hatred has courage and hatred is dear,

Hatred has virtue and hatred is here!

Odious enemy do not come near

There is no pity nor tenderness here,

There is no mercy just villainous fear!

“Driving the Moles Away” and “Don’t Tread on Me” are dramatically essential, but they’re overlong and have unnecessarily catalogy lyrics – The Residents persuasively express the feelings of the Moles, but their muse is on the nod. However, they rally and conclude the album spectacularly with “The Short War.”

The inevitable has finally commenced, and it’s more horrible than anyone could have suspected. Screeching sirens multiply, insinuated with the sound of electric drills – Dental Dread is a truly hot button, and The Residents give it a nice subliminal massage. Barking dogs are all over the place too, and they’re not the potential rescuers of Eskimo. In an unsettling visceral alternation of upward and forward motion, piercing sirens take an upward glissando and dissolve into a crescendo on sustained tones. The confusion feeds on itself as the piece reaches its peak: screams, unintelligible voices; static and low hums; high whoopings and blasts, electronic? vocal? instrumental? This is civilization, sanity, life itself in the Cuisinart, the imagery careening by too fast to be recognized, unless the sensation of loss and waste is a form of recognition.

At the height of this nightmare, a rubbery, high-register electronic line enters, suggesting a variation of “Driving the Moles Away.” And out of this line, a new, very low sound emerges. It no longer matters what the Moles wanted or didn’t want, or what the Chubs wanted to do for or to the Moles. The warring factions have scraped open the gate of Hell, and there’s plenty of room inside for everybody. This deep dragging sound reveals a yawning chasm, a presence you seem to feel even when it isn’t sounding. The slow fading down of the high-voiced line throws it ever-more plainly into relief, letting you hear each near-inaudible rustle and hum of the multi-headed sound. It has a mammalian feeling, a panting, almost growling – the Fenris Wolf, its open jaws scraping heaven and earth, not yet pouncing because it has all the time in the world, because there is no more time in the world. Finally the sound splits apart into obscenely present gasps and cries and hideous laughter, until everything suddenly implodes with a startling, visceral, backwards cymbal crash.

Of course there’s more. “Resolution?” turns you around 180 degrees, opening with a simple, even dainty, harpsichord line, accompanied by a steady pulse reminiscent of quiet blasts of escaping steam. Yes, society’s chugging along once again. A bass enters, shoring up things even further, but before you can relax the music stops and a new element enters: tremolo strings, taking a fast, loud crescendo into noise, a noise within which The Residents implant the sound of a metallic slash, perfectly capturing the image of a knife being brandished in your face. An ominous timpani figure nails down the sensation and becomes a funereal backdrop for repeated slashes. Then, inevitably, the steam-driven harpsichord picks up once again, sounding alongside this new evil. The Moles have been “assimilated” ghettoized, to the agony of both peoples. Now the two are strapped together, eyeball to eyeball, glaring at each other with implacable hatred and fear, instantly prepared for violence. The two musics stream together to the close of the album, exiting after a restatement of the “harmony has been restored” melody of “Back to Normality” – a quotation that goes beyond irony, into the bitterness and despair that fuel Mark of the Mole.

FOOTNOTES

1. Dave Warden, The Cryptic Guide to The Residents. San Francisco: Ralph Records, 1986, p. 8.

2. In 1984 they released footage of some of these performances, but alas their disappointing, lackluster Mole Show video never comes close to re-creating the musical invention or dramatic power of the show itself. If you want an idea of what the event sounded like, try to snag a copy of the now out-of-print bootleg LP, The Live Mole Show (1983).

3. In The Residents Radio Special (1977), they had Jay Clemm voice their contempt for the “typical dumb Texas redneck bigot.” “The South in the late ‘60s was not a pleasant place for anybody who had any kind of offbeat point of view about life at all. So it’s not particularly hard for me to see why The Residents were glad to get out of the South,” says Hardy Fox to Michael Goldberg in New Musical Express’ “I Left My Art in San Francisco,” 17 November 1979, p. 37.

Links to:

SONIC TRANSPORTS: The Residents Essay, part 5

SONIC TRANSPORTS: The Residents Contents

SONIC TRANSPORTS: Contents

For more on The Residents, see:

Film Review: The Eyes Scream

Film Review: Triple Trouble

Music Book: Historical Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Classical Music, Second Edition

Music Lecture: My Experiences of Surrealism in 20th-Century American Music

Music: SFCR Radio Show #7, Postmodernism, part 4: Three Contemporary Masters

Music: SFCR Radio Show #26, Surrealism in 20th-Century American Music

Music: SFCR Radio Show #27, 20th-Century Music on the March